When Gov. Gavin Newsom’s CARE Court launched in 2023, his administration projected the program could help steer up to 12,000 homeless Californians and others with severe mental illnesses into treatment.

But as of May, only about 2,000 people had been referred to the Community Assistance, Recovery and Empowerment Court, according to a recent state report. And it’s unclear how many of those had actually enrolled in the program and been connected to treatment.

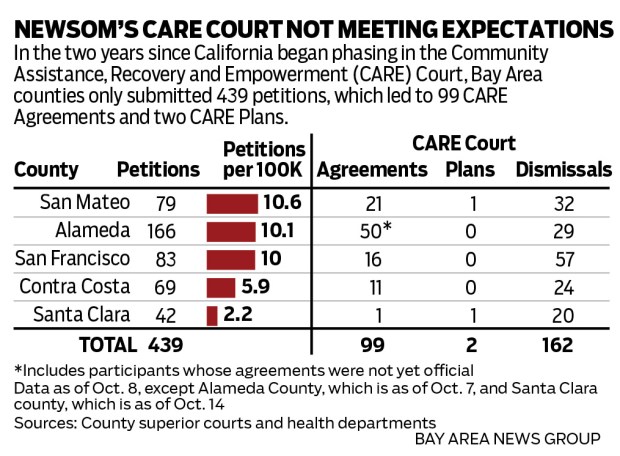

In the Bay Area, 439 referral petitions had been filed across the region’s five largest counties as of last month, according to a survey of local officials by this news organization. As a result of those petitions, only around 100 people were participating in the program.

Local officials and mental health advocates attribute CARE Court’s slower-than-expected start to strict eligibility requirements, bureaucratic procedures and a lack of awareness about how to refer people to the program.

“Overall in the state, there has been a smaller number than we initially anticipated,” said Soo Jung, a director with Santa Clara County’s Behavioral Health Services Department.

Newsom’s office, however, in a statement blamed some counties for “shirking their responsibilities” in adopting CARE Court, singling out Santa Clara County, which had enrolled just two people in the program. Alameda County, for comparison, had 27 CARE Court participants, with 23 more having agreed to enroll.

“It’s time for lagging counties to stop making excuses and start delivering the help Californians desperately need,” Newsom’s Deputy Communications Director Tara Gallegos said in the statement.

Santa Clara County Executive James Williams responded in a statement that the county has chosen to prioritize other treatment programs rather than “lengthy, costly and inadequate mechanisms like CARE Court.”

As officials clash over the program, some families with loved ones in CARE Court have grown frustrated with its limitations in requiring participants to accept treatment. Although people are generally referred to the court without their consent, supporters say it’s designed to facilitate services through a voluntary process.

When Jennifer Su petitioned to send her adult son to Contra Costa County’s CARE Court in January, she was hopeful that after years of watching him spiral into homelessness and addiction, he would finally get the help he desperately needed.

When Jennifer Su petitioned to send her adult son to Contra Costa County’s CARE Court in January, she was hopeful that after years of watching him spiral into homelessness and addiction, he would finally get the help he desperately needed.

Since then, however, her son has been arrested multiple times and spent months in jail, according to court and police records. Su said social workers assigned to his case through CARE Court have been unable to persuade him to accept medication or connect him with housing, an experience shared by other families across the state, mental health advocates said.

“I didn’t think we would be in this situation,” Su said. “It seems so clear it’s bad for him and it’s bad for society that he is not mandated to get help.”

Reached by phone, her son declined to comment and hung up. Contra Costa County health officials declined to discuss his case, but said it often takes repeated outreach before those with a serious mental illness are ready to accept treatment.

CARE Court works by allowing family members, first responders, health care providers and others to refer people with severe, untreated psychiatric issues to the program. If a person is determined eligible, a judge works with them and county health and court officials to develop a personalized treatment strategy. That can include medication, drug counseling and a spot in supportive housing or a residential care facility.

Participants who are resistant to treatment can be ordered to follow a “CARE plan.” They can’t be forced to accept services. However, those who refuse to comply can be referred for a conservatorship, which could lead to involuntary treatment or placement in a locked facility.

Mental health advocates said part of the reason for the program’s slow start is that family members and others can be overwhelmed by the petition process, including carefully documenting a person’s medical history. Another challenge: Law enforcement officials, nonprofit providers, health care personnel and the general public may not be aware that CARE Court is even an option.

In response, officials and advocates, including the National Alliance on Mental Illness, are offering outreach and training sessions to “ensure those who are interested in filing a CARE petition for a loved one understand if it is the right fit,” the alliance said in a statement.

But filing a petition is only the first step. Of the hundreds of petitions submitted in the Bay Area, just 99 resulted in voluntary “CARE agreements” as of last month, while only two led to court-ordered CARE plans.

CARE Court launched across the state in a staggered rollout. In the Bay Area, San Francisco opened its court in October 2023; San Mateo County in July 2024; and Santa Clara, Alameda and Contra Costa counties in December last year.

As of October, Santa Clara County’s CARE Court had received 42 petitions but established just one CARE agreement and one CARE plan. Local health officials said many of the petitions were dismissed due to the program’s eligibility requirements, including that participants be diagnosed with schizophrenia or another serious psychotic disorder.

“It narrows down who should be going through the CARE Court process,” said Jung with Santa Clara County’s behavioral health department.

Even so, county health officials said they have connected 60 people who were initially considered candidates for CARE Court to other treatment programs. Across all counties, people have been similarly diverted away from CARE Court at least 1,358 times, according to the state.

To boost enrollment in CARE Court, Newsom in October signed a bill to expand the eligibility requirements to include people diagnosed with serious bipolar disorder, and to streamline hearings to eliminate delays in accepting people into the program. But disability rights advocates, who generally oppose court-ordered treatment, argue the law could greatly expand eligibility without providing more funding for mental health services or housing.

Su has given up hope that CARE Court is the solution for her son. She wants the county to place him in a conservatorship, believing it’s the only way to return the son she remembers — a caring, outgoing young man and talented guitarist and artist.

“I appreciate the efforts CARE Court has made,” Su said, “but their hands are really tied with situations like my son.”