By Rachel Crumpler

Trying to get back on one’s feet in the community after leaving prison or jail is rarely easy. People often face steep hurdles finding housing, employment and health care. For those with serious mental illness, the transition can be even more difficult.

About two in five people who are incarcerated have a history of mental illness — roughly twice the prevalence of mental illness within the general adult population.

Many of them leave prison or jail without a job or even a place to live. Some may have a single outpatient mental health appointment scheduled and a 30-day supply of their medications. Others might just get handed a list of resources and phone numbers.

Too often, it isn’t enough.

Ted Zarzar, a psychiatrist who divides his time between UNC Health and Central Prison in Raleigh, previously told NC Health News the period where people reenter their communities is especially critical — and high-risk — for people with a mental illness.

Without a direct handoff to care and support, Zarzar said staying stable in the community is nearly impossible. Many people end up right back in a jail, prison or the hospital in a frustrating — and costly — cycle of recidivism. And taxpayers foot the bill: Incarceration in a North Carolina prison costs more than $54,000 a year.

It’s a cycle state leaders want to break — and they’re trying a new approach.

On Nov. 3, North Carolina officials announced a $9.5 million pilot program to provide intensive support to people with serious mental illnesses — such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and chronic post-traumatic stress disorder — as they reenter the community after incarceration. The goal: to reduce repeat encounters with the justice system and guide people to the help they need.

Kelly Crosbie talks about the launch of FACT teams in North Carolina on Nov. 3, 2025 at DHHS headquarters. “Providing alternatives to incarceration when it’s appropriate, and then supporting people upon their release from incarceration with things like treatment, but also housing and employment are critical if we’re going to stop the cycle of justice system involvement,” she said.

Kelly Crosbie talks about the launch of FACT teams in North Carolina on Nov. 3, 2025 at DHHS headquarters. “Providing alternatives to incarceration when it’s appropriate, and then supporting people upon their release from incarceration with things like treatment, but also housing and employment are critical if we’re going to stop the cycle of justice system involvement,” she said.

These Forensic Assertive Community Treatment, or FACT, teams will deliver personalized clinical and social support to justice-involved individuals with serious mental health needs who also present a medium to high risk of repeated criminal behavior.

“We want to make sure that they are effectively connected to the treatment and supports that they need,” said Kelly Crosbie, director of the state’s Department of Health and Human Services Division of Mental Health, Developmental Disabilities, and Substance Use Services. “It is good for them, it is good for their families and it is good for our communities.”

High-risk, high-needs population

The first FACT teams will be based in Pitt, New Hanover, Wake/Durham, Buncombe and Mecklenburg counties. Each team will receive $636,000 per year for three years — funding that comes from the $835 million in behavioral health funding the state legislature appropriated in the 2023-25 state budget to improve the state’s mental health system.

Teams are designed to tailor care based on a person’s needs — from mental health and substance use treatment to housing and employment support and assistance with daily living tasks.

North Carolina’s first lady, Anna Stein, has focused on supporting rehabilitation and reentry programs for people leaving incarceration and on reducing stigma against people with substance use and mental health disorders as two of her top priorities during her husband’s time as governor. She helped announce the new program at NC DHHS headquarters in Raleigh.

“It is critical that we address the intersection of mental health needs and the criminal justice system,” Stein said.

While the pilot program has been in the works for more than a year, its launch comes amid increased public attention on gaps in North Carolina’s criminal justice and mental health systems. On Aug. 22, Ukrainian refugee Iryna Zarutska was stabbed to death on a Charlotte light rail train. The man charged in her killing had been diagnosed with schizophrenia and was homeless at the time of the incident. He had been arrested more than a dozen times over two decades and spent more than five years in prison for armed robbery.

‘People want support’

Data shows that people with mental illnesses are overrepresented in incarcerated, probationary and paroled populations nationwide. Crosbie said that many people have mental health concerns and behaviors that contribute to their criminal involvement, and others see their conditions worsen behind bars. Some even develop new mental health conditions once they’re incarcerated.

That’s turned jails and prisons into de facto mental health institutions — even though they’re ill-equipped to manage the growing, complex mental health needs of those in their custody.

The FACT model builds on Assertive Community Treatment — a model of care developed in the 1970s when psychiatric hospitals across the nation closed and care shifted into the community. ACT uses multidisciplinary teams who constitute “walking hospitals” to bring treatment directly to community members with the most serious mental health challenges.

Forensic assertive community treatment, or FACT teams, adapts that model to serve a justice-involved population by pairing treatment with interventions to reduce risks for future criminal behavior.

Each North Carolina FACT team will include nine roles: a team leader, psychiatrist or nurse practitioner, nurse, mental health counselor, substance use counselor, peer support specialist, housing specialist, vocational/educational specialist and forensic navigator. The team members work collaboratively to go beyond traditional outpatient care and “wrap” services around them.

“This program in particular is for people with very severe mental health issues,” Crosbie said. “These are folks that probably need more than once every two weeks a 45-minute counseling appointment. They really need intensive support through that peer who can be with them every day if that’s what they need, through a doc who they can talk to every day if they need to, a clinical social worker who’s directing the rest of the team and providing counseling services to them.

“It’s just a much more intensive level of clinical services, in addition to some of those other life supports, like housing and employment.”

Crosbie said teams can meet clients anywhere — at home, in a park, a doctor’s appointment or even at a job interview.

That flexibility is key for client engagement, said Lacey Rutherford, FACT team lead in Buncombe County.

Each FACT team has the capacity to work with up to 30 clients — a smaller caseload to allow staff to meet each person’s intensive needs. Team members are available around the clock, with no time limit on how long they can work with someone to become stable in the community.

The Buncombe and Mecklenburg county teams are already operating and accepting referrals, Crosbie said. The remaining teams are expected to launch by the end of the calendar year. Referrals can come from law enforcement, court officials, community corrections, behavioral health care providers and even family members who think someone would benefit from FACT services.

Rutherford, who previously worked for two years on an assertive community treatment team in Buncombe and had clients with histories of incarceration, said she believes the specialized teams to serve justice-involved individuals will help better address unmet needs.

“People want support. They really do,” Rutherford said. “Of course, we’re going to have situations where people are going to be resistant to this — to treatment — but overall, this is something that these individuals haven’t had. They haven’t had support. They haven’t had people in their corner fighting for them.”

An emerging strategy

While FACT teams are new to North Carolina, the approach has been in limited use elsewhere since the 1990s.

One early FACT team was created in 1997 in Rochester, New York, by psychiatrist J. Steven Lamberti, who is also a professor of psychiatry at the University of Rochester Medical Center. Lamberti saw the gaps between the mental health and justice systems when many of his patients landed in jail. The program is still operating today, with Lamberti serving as team psychiatrist.

“FACT brings together best practices in community mental health with best practices in crime prevention,” Lamberti told NC Health News. “It’s a mobile one-stop shop to meet people’s needs medically, psychiatrically and socially.”

He described a typical FACT client as someone with a serious mental illness who may not recognize their condition and has previously refused treatment, living on the streets without stable housing or income — conditions that lead to frequent encounters with the justice system.

“At some point, they get involved in a survival crime like stealing food or aggressive panhandling because they’re starving and trying to get money,” Lamberti said. “If they get arrested, they’ll go to jail. It’s usually a misdemeanor charge, and they’ll be right back out on the streets.”

Breaking the cycle, Lamberti said, requires treatment, along with addressing the “criminogenic needs” that drive justice involvement — issues like housing instability, food insecurity, poor family relationships and more.

Lamberti published the first paper on forensic assertive community treatment in 2004. At the time, he identified 16 teams operating in nine states — though he noted differences in their structure. The number of teams has grown in recent years — aided by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration naming FACT among best practices in 2019, Lamberti said.

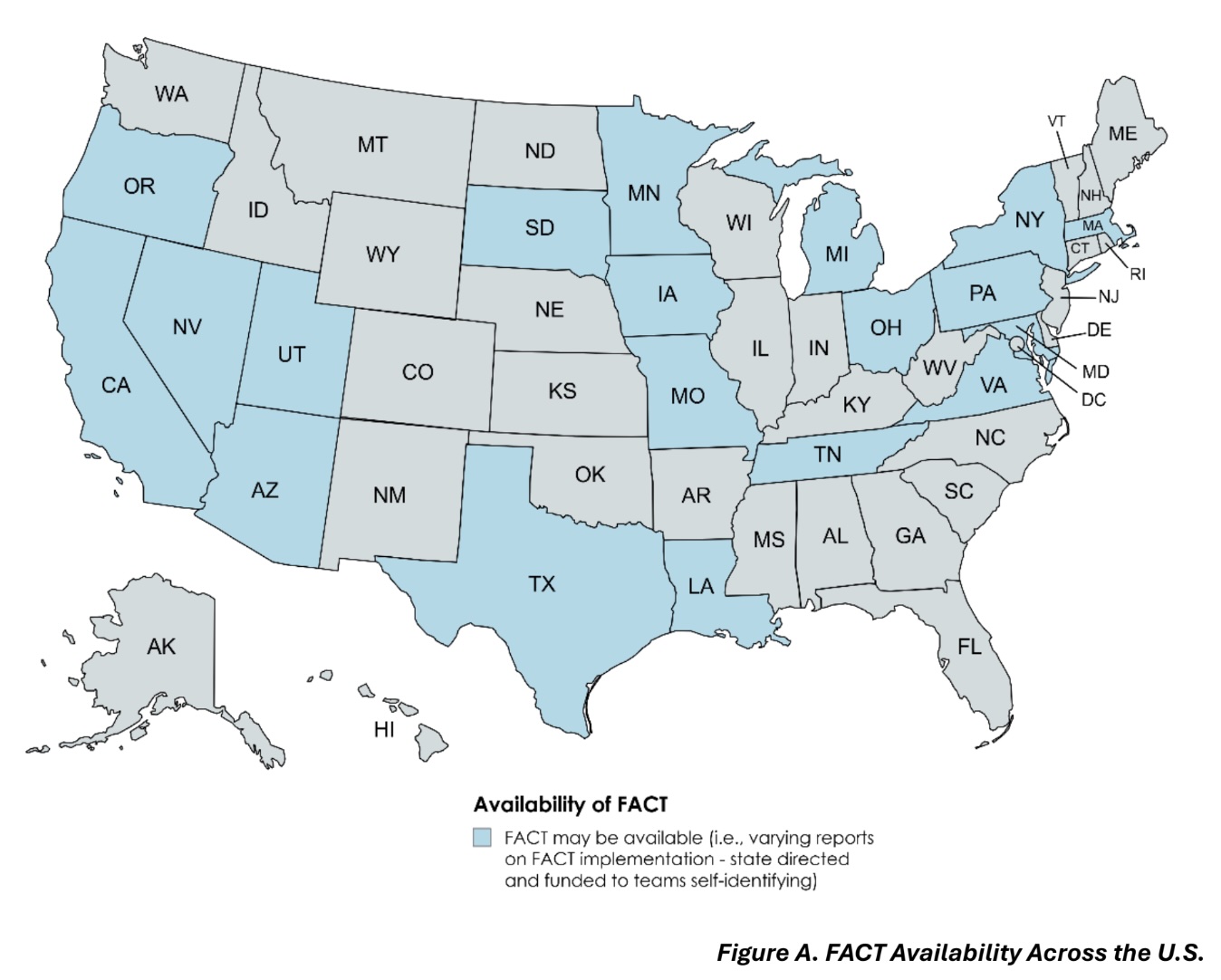

A recent June 2024 survey led by UNC Chapel Hill researcher Lorna Moser, who has spent her career providing training and evaluation of assertive community treatment, found FACT teams may be operating in 19 states.

Based on a 2024 national survey, researchers estimated that roughly 50 FACT teams may be operating across 19 states. Implementation remains limited, with generally only a few teams in each state. Lorna Moser, who led the survey, noted that determining the total number of teams is difficult because there’s variability in how FACT teams are defined. “I think that there’s teams out there that will call themselves a FACT team, simply because they’re serving a lot of folks that are justice-involved, but they’ve done very little to actually modify what they’re doing to try to align with the model,” Moser said.

Based on a 2024 national survey, researchers estimated that roughly 50 FACT teams may be operating across 19 states. Implementation remains limited, with generally only a few teams in each state. Lorna Moser, who led the survey, noted that determining the total number of teams is difficult because there’s variability in how FACT teams are defined. “I think that there’s teams out there that will call themselves a FACT team, simply because they’re serving a lot of folks that are justice-involved, but they’ve done very little to actually modify what they’re doing to try to align with the model,” Moser said.

In the past year, Lamberti said at least four states — including North Carolina — have launched FACT teams as state leaders look for better ways to serve this high-need population.

“People that are appropriate for FACT services are high service utilizers because they’re cycling in and out of jails and hospitals,” Lamberti said. “That’s very costly, not just financially but emotionally. These are human beings with families, and they and their families are suffering immensely by watching a loved one become homeless, cycle through and become incarcerated.

“For a variety of humanitarian and financial reasons, there’s really great interest [in FACT teams] on the part of the states.”

FACT is a relatively new service delivery model, so its effectiveness is still being gauged. So far, Lamberti said, the growing evidence base is showing that “outcomes are generally positive.” Evaluations have shown that FACT can help reduce days spent in jail and promote greater use of outpatient mental health services.

It also appears to be cost-effective. A 2022 study published in Psychiatric Services found that the Rochester FACT program was associated with a $1.50 return on investment for every $1 spent — largely by preventing hospitalization and incarceration. And that was without factoring in potential savings from other sources such as crime-related damages.

North Carolina health leaders said they’ll be monitoring the outcomes of North Carolina’s FACT teams closely.

“Our goal is that this is incredibly successful, and we’re able to replicate this in more counties,” Crosbie said.

This article first appeared on North Carolina Health News and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()