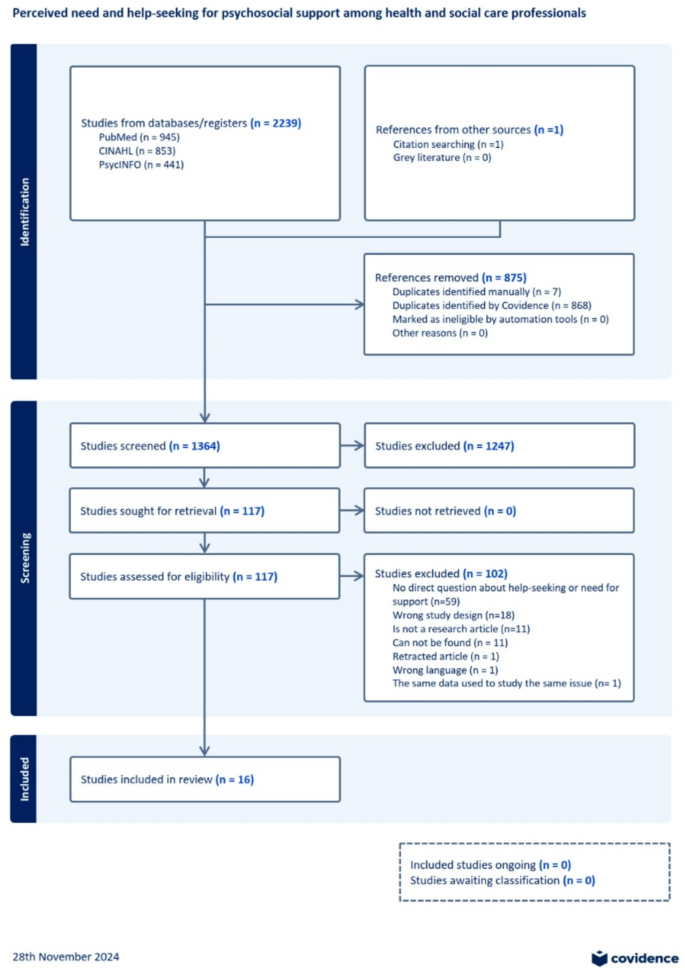

The database search yielded a total of 2,239 results, including 945 records from PubMed, 853 from CINAHL, and 441 from PsycINFO (Fig. 1). The Covidence tool identified and removed 868 duplicate entries, while an additional 7 duplicates were manually removed. Following the removal of duplicates, 1,364 studies remained for title and abstract screening. Based on this initial evaluation, 117 publications were selected for full-text review. Of these, 15 studies met the inclusion criteria. An additional publication, identified through reference screening of the selected studies, also met the inclusion criteria. Consequently, a total of 16 studies were included in the final review.

PRISMA flow diagram from Covidence tool

Characteristics of the sample

The majority of the studies (9 out of 16) were published in 2020 or later. The samples were geographically diverse, with no single country being predominant. Most studies employed a cross-sectional design (n = 15), while one study utilized a longitudinal design. Two studies employed mixed methods; however, only the quantitative results were included in this review. Sample sizes ranged from 27 to 51,406 participants. In ten studies, the sample size was fewer than 1,000, while six studies included more than 1,000 participants. The proportion of female participants across the studies averaged 56.3% (range: 13.3–100%). Two studies did not report gender distribution, and in one study, it was difficult to assess overall gender distribution across all age groups.

The study populations comprised physicians in 11 studies, nurses in one study, social care workers in one study, healthcare workers in one study, and both healthcare and social care workers in two studies.

Most of the studies focused exclusively on help-seeking behavior (n = 10), while three studies examined the need for support, and an additional three studies explored both outcomes (Table 1). These outcomes were measured using various self-reported questionnaires. Among the studies investigating the need for support, three focused solely on formal support or professional help, while the provider of support was unclear in the other three. Of the ten help-seeking studies, six investigated both formal and informal support. Another six reported only formal support or professional help-seeking, and in one study, the provider of support was not specified.

Table 1 Background information and results of the included studiesMeta-analysis

Meta-analysis was performed for both outcomes, the need for support (n = 6) and help-seeking behavior (n = 13).

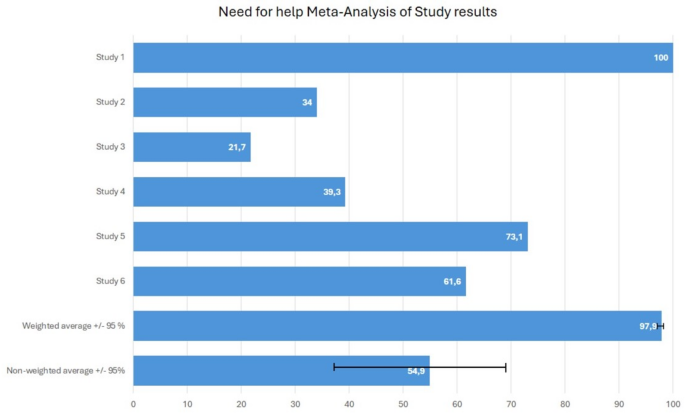

Need for support

The meta-analysis indicated that a weighted average of 97.9% and unweighted average of 54.9% (range: 34–100%, 95% CI 37.3% − 69.3%) of health and social care workers reported some form of need for psychosocial support (n = 6). In three of these studies, the need was specifically for formal support, while in the remaining three studies, the preferred source of support was not specified (Fig. 2).

The proportion of individuals reporting need for psychosocial support in included studies (n = 6). Study 1: This study had a large sample size (51,406), with all participants reporting at least some level of need for support, measured using a Likert scale. It had the greatest impact on the weighted average, which ultimately approached 100%. The study focused on the need for support from formal sources. Study 2: This study examined the need for support from formal sources among professionals who had experienced mental health problems within the past year. Study 3: In this study, the source of needed support was not specified. The need for support was assessed among professionals who had been exposed to armed conflict. Study 4: Similar to Study 3, the source of needed support was unclear. The need for support was evaluated among professionals whose patients had recently died. Study 5: This study assessed the need for support from formal sources. Study 6: The study investigated various Covid-19-related demands for mental health support

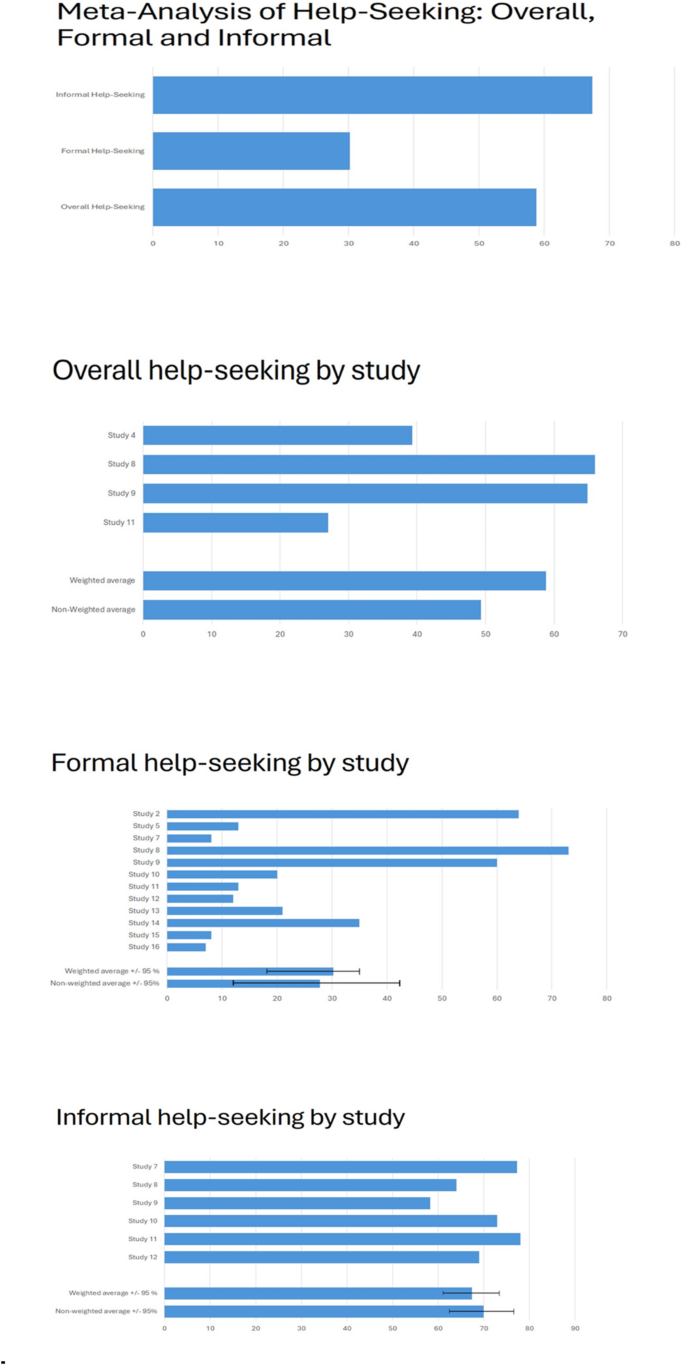

Help-seeking

The meta-analysis revealed that a weighted average of 58.8% and unweighted average of 49.3% (range: 27–66%) of health and social care workers sought some form of support, although the specific providers of support were not identified (n = 4).

We further analyzed formal and informal help-seeking. The weighted average for seeking formal support was 30.2% and unweighted average was 27.9% (range: 7.2–72%, 95% CI 15.0%-42.8%) among health and social care workers (n = 12). In contrast, a weighted average of 67.4% and unweighted average of 69.9% (range: 58.2–78%, 95% CI 63.8%-76.2%) of workers sought informal support (n = 6).

Specifically, 6 out of 13 studies on help-seeking behavior examined professionals who were already experiencing psychological distress or mental health problems, and an additional 2 studies focused on professionals whose patients had recently died (Fig. 3).

a A summary of the proportions of individuals reporting overall, formal and informal help-seeking. b The proportion of individuals reporting overall help-seeking (n = 4). c The proportion of individuals reporting formal help-seeking (n = 12). d The proportion of individuals reporting informal help-seeking (n = 6). Study 2. * Help-seeking was assessed exclusively among professionals who had experienced mental health problems within the past year. Study 4. * Help-seeking was evaluated among professionals whose patients had recently died. The source of support sought was not specified. Study 5: -. Study 7. **. Study 8. In this study, help-seeking results were stratified by three different age groups. We computed an overall result by combining data from these categories. For formal and informal help-seeking, we selected the values from the age group (younger practitioners) and support providers (formal: general practitioner, informal: friends) that had the highest reported rates. Help-seeking was evaluated among professionals with a lifetime history of depression. Study 9. Help-seeking was assessed among professionals who had ever experienced serious depression. Study 10. The focus was on professionals who had experienced emotional distress. Study 11: ** Help-seeking was assessed in professionals affected by the emotional impact of an adverse event. Study 12: ** The study evaluated help-seeking among professionals who had experienced secondary traumatic stress. Study 13: -. Study 14: -. Study 15: Help-seeking was assessed only among professionals who were attending physicians of a patient who died. Study 16: -. * Help-seeking was assessed only among professionals who had also expressed a need for support. ** Multiple values for informal and formal help-seeking were reported based on the provider of support (e.g., friends, colleagues, partner, or family). For the meta-analysis, we selected the highest reported values

Psychological distress and mental health problems among health and social care professionals

All included studies (n = 16) examined psychological distress or mental health problems among health and social care professionals. The proportion of participants reporting mental health problems or psychological distress could be assessed in 12 studies. Across these studies, the average prevalence of mental health problems was 55.3% (range: 26.7–95.9%), encompassing conditions such as occupational stress, anxiety, depression, and PTSD symptoms. Variability in prevalence rates was primarily due to differences in study scope and the types of mental health problems assessed. For example, in the study by Zhang et al. (Study 1 [Zhang et al., 2023]), 95.9% of nurses reported some level of occupational stress, whereas in the study by Schiff et al. (Study 3 [Schiff et al., 2018]), 26.7% of social care workers exhibited symptoms of PTSD.

Additionally, two studies reported suicidal ideation among healthcare professionals. In the study by Shanafelt et al. (Study 16 [Shanafelt et al., 2011]), 6.4% of surgeons reported experiencing suicidal ideation. In the study by Fridner et al. (Study 13 [Fridner et al., 2012]), 30% of professionals currently experiencing psychological ill-health reported suicidal thoughts. Twelve of the included studies assessed help-seeking behavior or the need for support in populations that had already experienced psychological distress, such as depression, burnout, or trauma from adverse events (e.g., patient suicide, medical error, or other traumatic incidents).

Alcohol and substance use

Alcohol and substance use were reported in four studies (25%). Six studies (37.5%) assessed stigma or other barriers to help-seeking.

Styra et al. (Study 7 [Styra et al., 2022]) reported that 26.4% of allied health workers (including social workers), 27.5% of nurses, and 25.0% of physicians had initiated or increased alcohol consumption, though this result was not statistically significant (p = 0.793). Additionally, 10.9% of allied health workers, 19.3% of nurses, and 8.5% of physicians reported using hypnotics to aid sleep (p

King et al. (Study 10 [King et al., 1992]) found that 18 out of 133 doctors (13.5%) had increased their alcohol intake to cope with emotional distress. Similarly, Grover et al. (Study 5 [Grover et al., 2019]) reported that 25.5% of doctors started or increased substance use due to work-related stress, and 13.2% admitted to self-medicating with drugs for psychiatric disorders. Jones et al. (Study 14 [Jones et al., 2018]) found that 3.3% of military doctors reported having an alcohol problem within the past three years, and 13.6% had sought help for alcohol use.

Stigma and barriers to help-seeking

Barriers to help-seeking were frequently reported across studies. Only the medical profession is mentioned because the available data on stigma and barriers to help-seeking came exclusively from studies involving physicians.

Wijeratne et al. (Study 8 [Wijeratne at al., 2021]) found that fear of lack of confidentiality (41–59%) and possible embarrassment (26–43%) were the most commonly cited barriers to seeking support in all age groups. Stigma was reported as a barrier by 15–30% of participants. A significant proportion of doctors believed that experiencing anxiety or depression was a sign of personal weakness (ranging from 31% in older doctors to 51% in younger doctors). Many also found the idea of being a patient embarrassing (48–63%). Ramzi et al. (Study 9 [Ramzi et al., 2021]) reported that fear of lack of confidentiality (61.9%) was the most common barrier to help-seeking, followed by embarrassment (44.8%) and stigmatizing attitudes (32.9%). King et al. (Study 10) found that 10 out of 133 doctors (7.5%) were embarrassed to seek help, and 7 doctors (5.3%) were concerned about confidentiality.

In the study by Grover et al. (Study 5), 58.1% of doctors believed that people were reluctant to seek help within the institution due to fear of being labeled as weak or unable to handle pressure. Additionally, 54.6% identified stigma as a barrier, and 36.3% cited concerns about confidentiality.

Jones et al. (Study 14) found that 67.3% of military doctors were concerned about stigmatization and did not want a mental health problem to be on their medical records. The most common perceived barrier to care was difficulty obtaining time off work for treatment (45.8%). A majority of participants (59.6%) expressed a preference for solving problems independently, while 65.5% reported that seeking support would make them feel inadequate. Furthermore, 48.3% found help-seeking too embarrassing, and 23.7% were worried about confidentiality.

Finally, Shanafelt et al. (Study 16) reported that 38.8% of surgeons would be reluctant to seek help for mental health problems due to concerns that doing so might negatively impact their license to practice medicine.

It was not possible to evaluate the costs associated with mental health problems or the consequences of not seeking help, as the majority of included studies did not provide relevant data. Only one study (Study 10) reported information regarding time off work. In this study, 12 out of 133 doctors (9%) indicated that they had taken time off work due to emotional distress. None of the included studies provided estimates of the financial costs associated with mental health outcomes or their impact on workplace productivity.