This section starts with a comparison between the psychologists who answered for open-ended question and those who did not. Next, the findings of qualitative conventional content analysis of the comments are reported with a look at identified themes in relation to emotional tone. Eventually, we check whether the emotional valence and thematic categories of the provided comments differ depending on basic participants’ characteristics.

Between group comparisons

First, the groups of participants providing and not providing the comment for open-ended question in the questionnaire were compared quantitatively. No differences were found in terms of age and gender. Psychologists who have written their answers had slightly shorter professional seniority (mean M = 10.72 vs. M = 12.02 respectively), but when specifically, the years of work experience in medical practice were counted there was no difference. A bigger fraction of commenters had no clinical psychologist or psychotherapist certification than among non-commenters (85% vs. 76% and 60.1% vs. 46.3% respectively). The detailed results of comparing analysis are presented in Table 1.

Table 1 Sociodemographic and professional characteristics with comparison between commenters and non-commenters.

Although official statistics are lacking, a comparison with one national report9 shows that our sample presents similar gender proportions and age, with slightly longer mean professional experience (8.14 years vs. 10.75 in present sample).

Qualitative analysisEmotional valence

Emotional expression inscribed by participants appeared to be rather equally distributed. Of all the comments, 68 were rated as neutral (35.23%), and the same number as positive, with negative emotionality attributed to 57 (29.53%) statements. However, the extreme values (+ 2 for positive or -2 for negative) were given only to 10 and 5 comments, respectively.

Content analysis

The dataset analysis generated seven main categories describing the comments’ content. The first category (C1) reflected rejection of PP along with justifications and was represented by 32 statements (16.58% of 193). The second category (C2) contained doubts and perceived barriers and had 42 statements (21.76%). The third category (C3) was composed of necessary requirements that must be met before PP can be granted and had 75 comments (38.86%), making it the largest set. The fourth category (C4) included thoughts about the scope and limitations of PP, represented by 14 comments (7.25%). The fifth category (C5) contained statements supporting PP and envisaging benefits, with 42 comments (21.76%). The sixth category (C6) listed additional rights that should be granted alongside PP and included 15 entries (7.77%). The last category (C7), with 22 comments (11.40%), gathered other issues not directly connected to the subject studied.

Each entry received at least one category: 144 statements (74.61%) were assigned to one, 48 (28.87%) to two categories, and only one (0.52%) to three. The table with detailed examples of comments in each category and thematic group is available in supplementary materials (Suppl. TS1).

First category

This category grouped opinions stating direct opposition to the idea of PP for psychologists, in many cases accompanied by justification. Inter-rater reliability for this category reached 96.2%, and Fleiss’s kappa was κ = 0.86. A leading argument against prescribing was the assumed lack of proper professional competence. Concerns focused on the ability to make the right choice of medication, recognize interactions, and monitor the influence of pharmaceutical treatment on the human body. The view expressed was that only medically trained professionals with strong clinical backgrounds can competently prescribe medications.

In addition, some opinions presented negative emotionality. Others pointed to the necessity of general legal regulations concerning the profession of psychology and the poor quality of education and training. Several participants also noted uncomfortable overlaps of responsibilities, conflicting approaches to patient care, or risks associated with psychologists shifting professional identity.

“This is an extremely bad and dangerous idea considering the current state of education of psychologists in Poland and the state of this profession.” (P138).

Second category

The second category grouped perceived barriers and doubts. The participants considered the idea risky or currently impossible to implement. Agreement of raters reached 94.8% (Fleiss’s kappa κ = 0.83). Main dilemmas focused on risks and possible abuse of prescriptive rights, although precise specification of these risks was scarce. The most common concerns were about increased access to psychotropic drugs, fears about certain classes of medications, medicalization of patients’ problems, and irresponsible prescribing.

“First of all, this should be used to discontinue medications, but probably, in general, it will only increase their availability.” (P105).

The doubts here also referred to professional identity, psychiatrists as colleagues or critics of the idea, patients losing deeper psychological support, and confusion about professional roles in mental health care. As in the C1, many noted the uncertainty of legal regulations as an additional serious constraint, which resulted in thematic overlap. This was resolved by interpreting the comments in full context and assessing whether legal regulations were presented as unmanageable or as more temporary barriers.

Third category

This category grouped requirements and conditions for psychologists that were proposed as legally approved and obligatory before PP could be granted. Reliability between raters was 93.1% (Fleiss’s κ = 0.85). Common issues included mandatory rigorous postgraduate education, supervision, and professional experience in healthcare settings. This was the largest category, totaling 39% of all comments. However, opinions regarding necessary qualifications were often vague.

“I admit that it was easy to answer the questions until the moment of asking ‘to whom…’ And with each group, doubts and thoughts about the consequences appeared. I can’t imagine it without additional training and an exam.” (P111).

Psychotherapists and clinical psychologists were most often indicated as the groups best equipped to obtain qualifications, specifically those with a Ph.D. in psychology or medical sciences. Still, the need for additional obligatory education was emphasized.

Some participants stressed that specialized training in areas such as human physiology, pharmacology, or neurobiology should be required before qualification for prescribing rights. Others highlighted the role of professional experience, preferably measured in years and obtained in public healthcare institutions. The importance of supervision under the tutelage of a psychiatrist was also stressed.

“In order to prescribe medication, a psychologist should work for at least 5 years in a psychiatric hospital and complete a one-year course or one-year postgraduate studies.” (P3).

Another group of comments expressed that granting prescribing rights requires a renewed approach and comprehensive changes in psychological education. This was particularly evident in calls for clearer divisions between specialty tracks, updated curricula, and standardized length and quality of education. Additional proposals included making the exam independent of the training institution, providing a national certificate, and treating psychologists as medical professionals.

Fourth category

This category concerned the specification of rights that might be granted to psychologists. Inter-rater agreement reached 98.6%, with Fleiss’s kappa κ = 0.88. Examples included limiting prescriptions to medications a patient is already taking, restricting PP to a shortlist of drugs, and allowing it only in exceptional situations.

“It would be necessary to create a list of drugs that the psychologist: a) can prescribe on his own; b) may prolong medications prescribed by a psychiatrist, especially when a quick visit to a psychiatrist is difficult; c) cannot prescribe at all.” (P1).

Participants also proposed limitations, such as excluding medications with higher risk of harmful interactions, serious side effects, or potential for dependence. At the same time, acceptable categories included tranquilizers, sleep aids, antidepressants, and drugs for adaptation disorders—often with emphasis on medications with milder physiological effects.

Moreover, most adequate contexts for PP were suggested, such as intervention when psychiatric help is unavailable, as a first attempt at pharmacotherapy added to psychological care, and always with the option of consulting a physician. For some, the right to extend prescriptions already given by a psychiatrist seemed more acceptable than independent prescribing.

Fifth category

This category grouped comments on possible benefits of PP for patients, the healthcare system, or psychologists. Also included were supportive statements or encouragement without detailed justification. Agreement reached 95.1% (Fleiss’s κ = 0.85).

In comments supporting PP, participants expressed gratitude and appreciation for exploring the topic, engagement, and enthusiasm. Many emphasized potential patient benefits, such as more precise diagnoses, better adjustment of medication, and closer monitoring due to frequent contact.

“Based on my experience, I think that more frequent contact between the psychologist/psychotherapist and the patient gives the opportunity to adjust pharmacotherapy in the most beneficial way for the patient.” (P70).

One participant elaborated further (see supplementary materials), showing the link between psychologists’ skills, diagnostic measures and accuracy compared with medical interviewing alone, which may not cover complex cases. These skills, it was argued, might also help reduce unnecessary medical treatment and relieve overburdened medical staff.

Other comments noted benefits such as greater accessibility to mental health care, particularly for adolescents and young adults, a more holistic biopsychosocial approach, and fuller use of psychologists’ existing competences. Some highlighted that in case of granting PP psychiatric services would be reserved for the most urgent cases. Further, the underserved groups could more easily get adequate and timely care.

Sixth category

This category described rights that could accompany or broaden PP, with inter-rater agreement reaching 99.7% and Fleiss’s κ = 0.98. Common examples included the right to make psychiatric diagnoses and thereby issue certificates, referrals to specialists, or sick leave documentation.

“It is difficult for me to comment on this matter, because in my opinion the more important issue is the possibility of issuing a short-term sick leave, or the officially recognized certificates (i.e., without the need for a doctor, to copy them from our opinions).” (P20).

Seventh category

The last category grouped comments not directly related to PP, with inter-rater agreement of 96.2% (Fleiss’s κ = 0.82). For the sake of order, only the general theme is presented, but these entries were not substantively analyzed due to their divergence from the study’s focus. Included here were remarks about the structure of the questionnaire, opinions about mental health in the general population, accessibility of psychiatric care, personal preferences or experiences, and comments regarding national legal regulations of psychology as a profession.

Emotional valence in relation to thematic categories

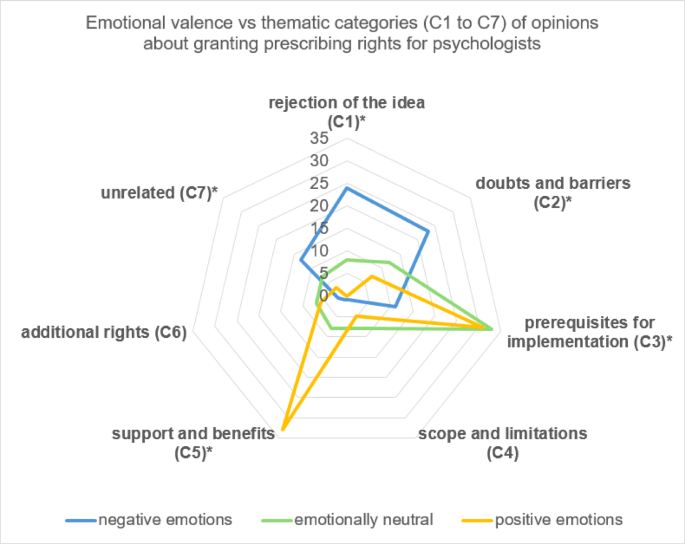

We analyzed the distribution of opinions in terms of their emotional valence using a quantitative approach with Pearson’s χ² test. Significant differences emerged across 5 of 7 categories (χ2 values from 10.26 to 46.01; all ps 2 = 4.62, p = 0.99) and C6 listing other rights alongside PP (χ² = 2.15, p = 0.34). Notably, these two categories contained fewer opinions, which may have prevented statistical significance.

The distribution of emotional valence levels between categories is shown in Fig. 1. Most negative opinions were assigned to categories opposing PP, describing barriers, or unrelated comments. Neutral opinions were largely assigned to prerequisites, with the rest spread across other categories. Positive comments were concentrated mainly on the category supporting the idea (C5) and suggesting prerequisites for implementation of PP (C3).

Frequencies of comments in each thematic category distributed according to three levels of emotional valence: positive, neutral and negative. *Significant effect of emotional valence on distribution within a thematic category.

Participants’ characteristics in relation to emotional valence and thematic categories

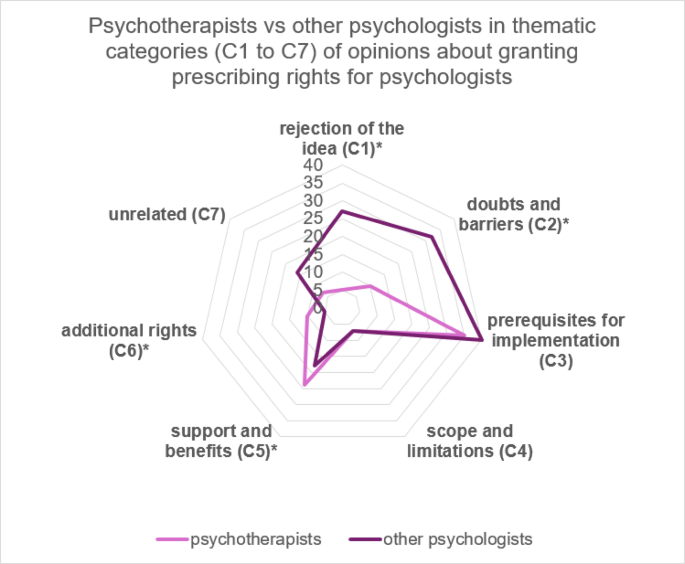

Further analysis showed that gender, age group or years of professional experience were not observed to have a meaningful interaction with thematic categories (the highest χ² = 2.55, p > 0.1 for all categories) or emotional valence (highest χ² = 1.25, p > 0.5). Working in public healthcare, having clinical psychologist title also did not reveal relationship with the outcome variables ( χ² = 0.07, p = 0.97 and χ² = 3.22, p = 0.2 respectively for emotional valence; the highest and χ² = 0.69, all p > 0.4 and χ² = 0.82, p > 0.36 respectively for the thematic categories). The only difference that was observed was between psychologists having psychotherapeutic qualifications (n = 77) or not (n = 116). Figure 2 presents the details of distribution differences in thematic categories according to participants being or not a psychotherapist.

Frequencies of comments in each thematic category distributed according to participants being or not a psychotherapist. *Significant effect of being/not being psychotherapist on comments distribution within a category.

The differences between the two professions were visible in 4 out of 7 thematic categories, namely rejection of the idea of PP (C1), doubts and barriers (C2), support (C5) and additional rights (C6) – χ² from 4.86 to 6.24, all p ≤ 0.05. Thie psychotherapists’ group in general appeared more positive in their emotional expression (χ² = 20.55, p