Study selection process

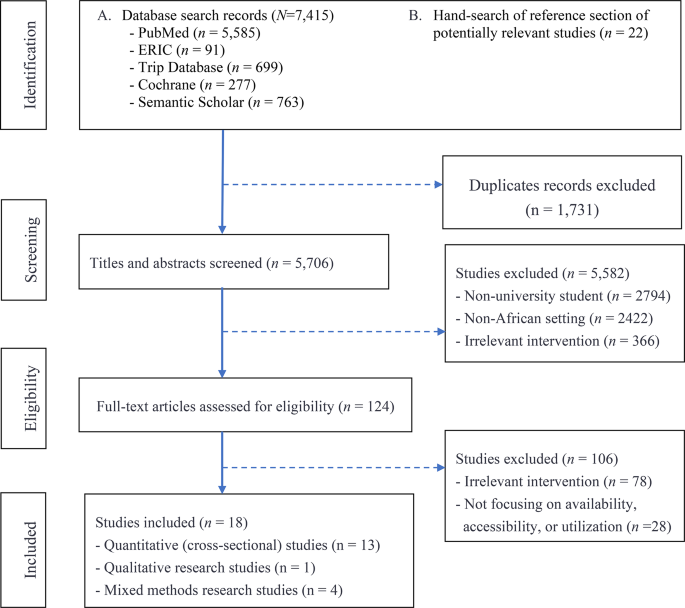

Figure 1 presents a flow diagram illustrating the literature search process, based on PRISMA guidelines [47]. Searches from five databases, including a hand search, identified 7,437 potentially relevant studies. Excluding 1,731 duplicates, the titles and abstracts of the remaining 5,706 studies were screened, resulting in the exclusion of 5,582 records for the reasons outlined. Inter-rater agreement for data screening indicated strong agreement, with a Cohen’s Kappa of 0.85. Further assessment of the full texts of the remaining 124 studies for eligibility resulted in the exclusion of 106 studies. Altogether, 18 studies met our inclusion criteria (13 quantitative [cross-sectional] studies, 1 qualitative study, and 4 mixed methods studies).

PRISMA flow diagram depicting literature search and selection process

Characteristics of included studies

Table 1 presents the basic characteristics of 18 studies involving 57,949 students from eight countries: South Africa (4 studies), Ethiopia (3 studies), Egypt (3 studies), Nigeria (2 studies), Sudan (2 studies), Tanzania (2 studies), Kenya (1 study), and Cameroon (1 study). These studies were published between 2010 and 2024, with over half (56%, n = 10) published between 2019 and 2024. The sample size ranged from 18 to 28,516 students (Median = 639, Mean = 3219, SD = 7529). Two-thirds (67%) of these studies were conducted in public universities, 16 studies (89%) included undergraduate students, and five studies (28%) included students in a medical program. The percentage of female students ranged from 40% to 71% (Mean = 60%). For most studies, the mean age of students was approximately 21 years. In eight studies, random sampling techniques were employed. In terms of type of mental health-related problem, three studies each focused on common mental disorders [22, 24, 48], psychological distress [49,50,51], and stress [25, 28, 52]; two studies focused on mental distress [48, 53]; and one study each focused on anxiety and depression [23], schizophrenia [53], and emotional distress [54]. Different self-reporting screening tools were used to assess mental health outcomes, including the 10-item Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) [23]; self-reporting questionnaire to evaluate mental disorders [16, 55]; General Health Questionnaire to assess psychological distress [49]; investigator developed questionnaires to assess stress [25, 28]; three questionnaires (Medical Outcomes Survey social support survey, Arabic Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale, and Arabic WHO Quality of Life Brief questionnaire) to assess depression, anxiety, and stress [51].

Table 1 Characteristics of included studiesMethodological quality of included studies

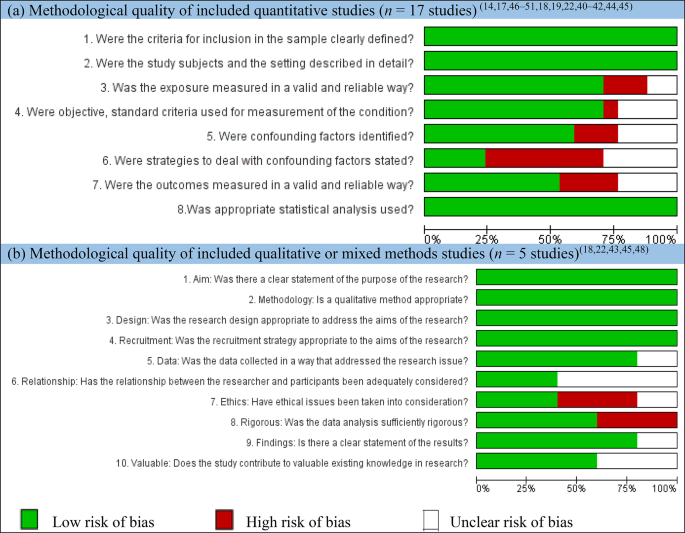

We judged the risk of bias in the included quantitative studies as moderate, with 17 studies having clearly defined inclusion criteria, subjects and settings being described in detail, and appropriate statistical analysis being used (Fig. 2 upper panel). However, in about one-half of these studies, strategies to deal with confounding factors were not clearly stated. Similarly, the risk of bias in the included qualitative or mixed methods studies (Fig. 2, lower panel) was judged to be moderate, with all five studies having a clear statement of the research purpose, appropriate use of qualitative methods, a research design suitable for the research aim, and an appropriate recruitment strategy. However, in over one-half of the studies, it was unclear whether the relationship between the researcher and participants was adequately considered.

Authors’ judgments about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included (a) cross-sectional studies and (b) qualitative or mixed methods studies

Available sources of MHSS

Based on our review, availability of MHSS was defined in terms of existence of a facility where the service is provided (e.g., “Mental health services were available at the student clinic… [p.4]” [23]); existence of formal or informal sources of MHSS (e.g., “… students mainly rely on informal sources of help such as their fellow students…[p.105]” [24]); or nature of service being provided (e.g. “… Kenyan universities offer social support to students in the form of counselling… [p.142]” [27]). Data on available MHSS were extractable from 61% (11/18) of included studies (Table 2). Informal sources of MHSS were the most frequently cited category, cited 25 times. This was followed by the facility/office where the service is available, cited 19 times. Formal sources and nature of MHSS were the least cited categories, cited 15 and 11 times, respectively. By formal sources, we refer to people who have accredited professional training to provide MHSS (e.g., psychiatrist, psychologist, etc.) whereas informal sources refer to those without such training (e.g., friends, parents, family members, etc.).

Table 2 Number and percentage of available sources of mental health services or support

Available informal sources of MHSS, including friends (classmates, roommates, and intimate partners) and parents (family, elders, siblings, and other relatives), were the most frequently cited, mentioned in seven (39%) and five (27%) studies, respectively. Administrative staff/auxiliary police and other sources (e.g., mass media, reading a book, or watching TV) were the least cited, each mentioned in one study.

Available formal sources of MHSS, including mental health professionals (counselors) and doctors (including general practitioners, physicians, or healthcare providers), were the most frequently cited, mentioned in five (28%) and four (22%) of the studies, respectively. Interestingly, only one study mentioned a psychiatrist as an available formal source of MHSS.

Facility/office including counseling unit and referral district hospitals were the most frequently cited available sources of MHSS, each cited in four (22%) studies. The least cited sources of MHSS were psychosocial support center, students’ union office, and the dean of students’ office, each mentioned in one study.

Nature of MHSS including social support and use of medication were the most frequently cited nature of MHSS, each mentioned in three (17%) studies. Psychiatric care, individual interpersonal psychotherapy (talk therapy), and personal coping strategies were each cited in one study.

Accessible sources of MHSS and associated factors

In this review, the extent to which students accessed MHSS was measured by the proportion of students seeking mental help from formal or informal sources. Mental help seeking is referred to as “the tendency of students to reach out for assistance amidst stressful situations (p.99) [24] or “the act of seeking assistance for mental health issues, which may involve accessing professional mental health services, consulting friends or family members, or engaging with support groups” (p.2) [56]. Where data on accessibility were available from at least two studies, meta-analysis was performed using a random effects model and the pooled proportion was reported with a 95% confidence level.

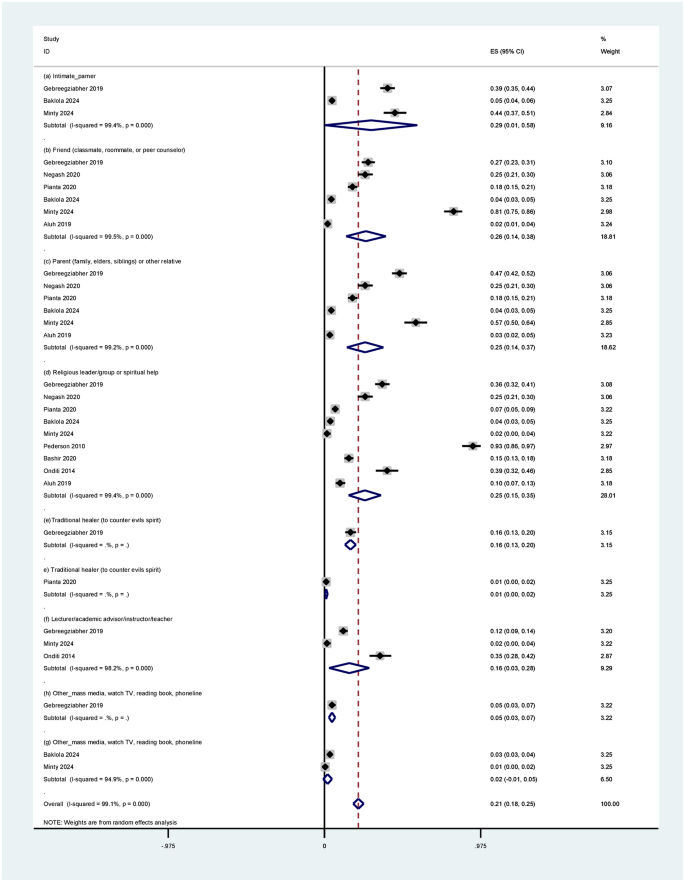

Accessible informal sources of MHSS – seven accessible informal sources of MHSS were identified: religious leader or spiritual help; friend (classmate or roommate); parent (family, elders, siblings, or other relative); traditional healer; intimate partner; institution-based sources (lecturer, academic advisor, or instructor); and others (mass media, TV watching, reading a book, calling phone line). Meta-analyzable data were obtained from nine studies, including 4,650 students. The overall pooled proportion (estimated using a random effect model) of students who accessed informal sources of MHSS was 21% (95% CI; 16% − 25%) (Fig. 3). However, given the significant heterogeneity (I2 = 99.2%, p = 0.000), this finding should be interpreted with caution. In one study [24], three other accessible informal sources of MHSS were cited: student union (36%), dean of students (33%), and administrative staff/auxiliary police (28%). A second study [57] identified four additional accessible informal sources of MHSS: private hospital (50.19%), district hospital (39.7%), medical social center (5.06%), and pharmacy shop (2.81%).

Forest plot of pooled proportion of students accessing informal sources of mental health services or support (based on random effect models with 95% confidence interval)

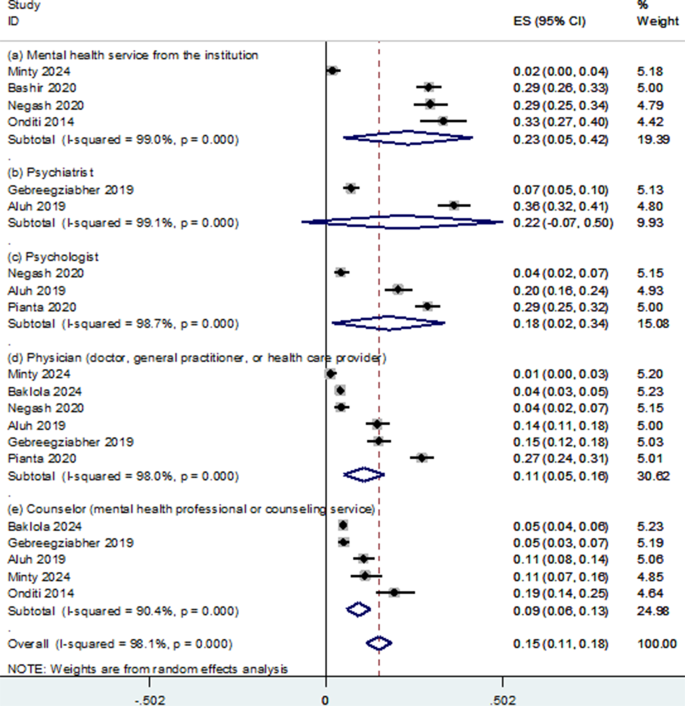

Accessible formal sources of MHSS – Five accessible formal sources of MHSS were identified: institutional (mental health service from the college); psychiatrist; psychologist; physician (doctor, general practitioner, or healthcare provider); and counselor (mental health professional). Meta-analyzable data were obtained from nine studies (4,650 students). The pooled proportion of students who accessed formal sources of MHSS was 15% (95% CI: 11% − 18%), however, given the evidence of significant heterogeneity (I2 = 98.1%, p = 0.000), this finding should be interpreted with caution (Fig. 4).

Forest plot of pooled proportion of students accessing formal sources of mental health services or support (based on random effect models with 95% confidence interval)

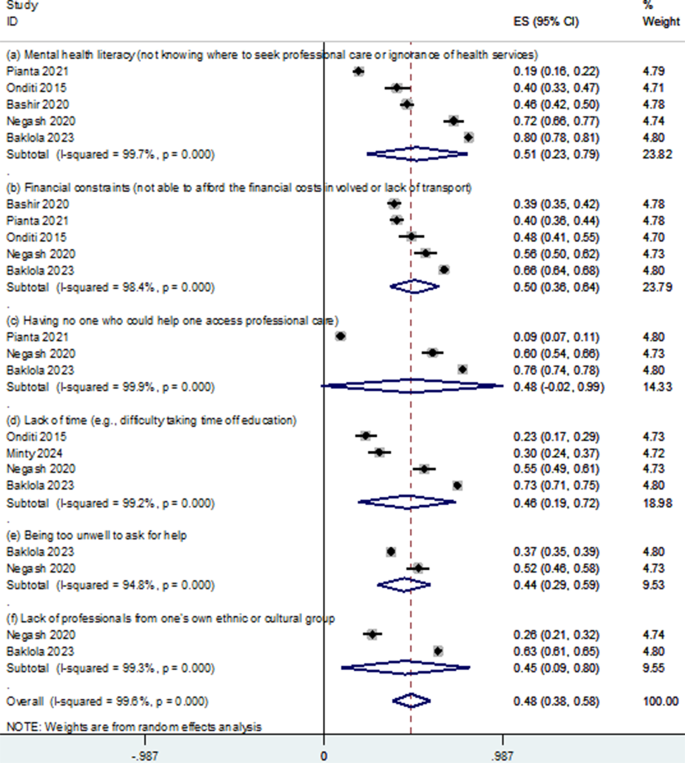

Instrumental-related barriers to access of MHSS – Seven types of instrumental-related barriers were identified, with meta-analyzable data obtainable from six studies (3,855 students): (a) mental health literacy (not knowing where to seek professional care or ignorance of health services); (b) financial constraints (inability to afford the financial costs involved or lack of transport); (c) having no one who could help one access professional care; (d) lack of time (e.g., difficulty taking time off education); (e) being too unwell to ask for help; and (f) lack of professionals from one’s own ethnic or cultural group. The pooled proportion of students citing these seven barriers was 48% (95% CI; 38% − 58%) (Fig. 5). In addition, in one study, it was reported that 42% of the students had no information at all about mental illness [23]. In one qualitative study [50], it was reported that students were not informed about the availability and benefits of guidance and counseling services in universities. In this study, a student focus group discussant commented, “If the services are there, they are not known, we should be made aware of such.” Another student remarked, “We should be told about where the guidance and counselling office are, and the services offered there so that we know who to see when we have problems.” Complementary findings from one mixed methods study [27] supported the findings related to barriers, including a lack of knowledge about counseling services, financial constraints, and insufficient time. In one study [24], 48% of students cited the location of the counseling center or the lack of a good environment as a barrier. Adverse social events were cited as a barrier in one study [50], and an insufficient number of qualified personnel and the use of denial as a coping style were identified as barriers in another study [27].

Forest plot of pooled proportion of students citing instrumental-related barriers to access of mental health services or support (based on random effect models with 95% confidence interval)

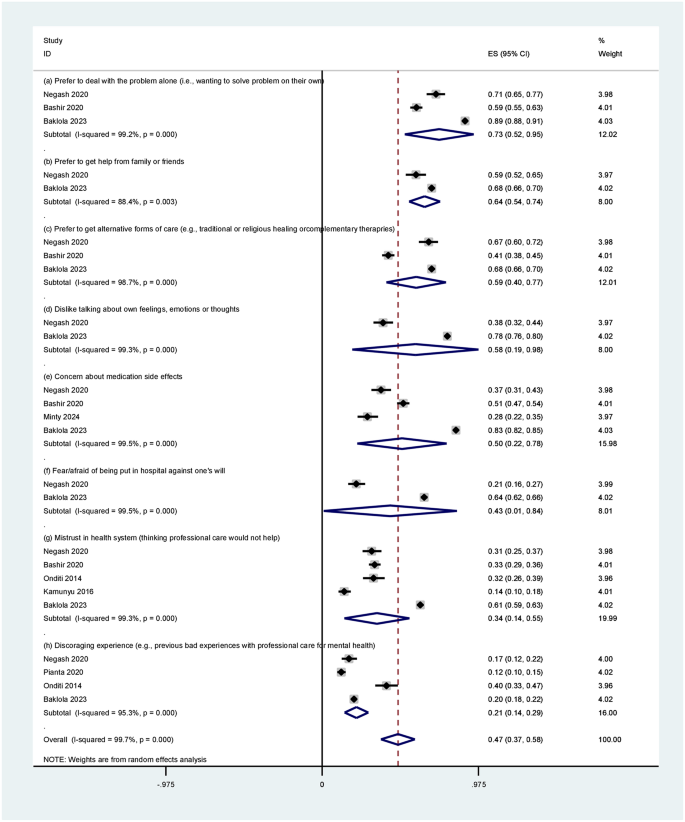

Attitudinal-related barriers to access of MHSS – Eight types of attitudinal-related barriers were identified, with meta-analyzable data obtainable from seven studies (4,288 students): (a) prefer to deal with the problem alone (i.e., wanting to solve the problem on their own); (b) prefer to get help from family or friends; (c) prefer to get al.ternative forms of care (e.g., traditional or religious healing or complementary therapies); (d) dislike talking about own feelings, emotions, or thoughts; (e) concern about medication side effects; (f) fear/afraid of being put in hospital against one’s will; (g) mistrust in health system (thinking professional care would not help); and (h) discouraging experience (e.g., previous bad experiences with professional care for mental health). The pooled proportion of students citing these five barriers was 47% (95% CI: 37%-58%) (Fig. 6). In addition, a mixed-methods study [25] found that unfair treatment from college sources of help was a barrier to accessing MHSS, and 31% of the students cited a lack of caring language as a significant barrier. In addition, other attitudinal-related barriers reported included thinking the problem would getter by itself (74.4%) [16]; being worried of uncertainties surrounding mental health diagnosis or fear of the unknown (59%); and not recognizing or knowing what signs or symptoms are related to psychological problems (58%) [49]. Finally, in a mixed-methods study [28], three attitudinal-related barriers reported included a lack of confidence in counselors, peer pressure, and a preference for seeking help from significant others and the Internet. Other attitudinal-related barriers to access to MHSS included methods of communication used to seek help from institutional sources when in stressful situation (e.g., face-to-face [83%], phone call [37%], email [16%], and letter writing [11%] [24] and student’s gender and other demographic facxtors such as religion, ethnicity, marital status, residence, area of growing, family history of mental illness, and substance use [16].

Forest plot of pooled proportion of students citing attitudinal-related barriers to access of mental health services or support (based on random effect models with 95% confidence interval)

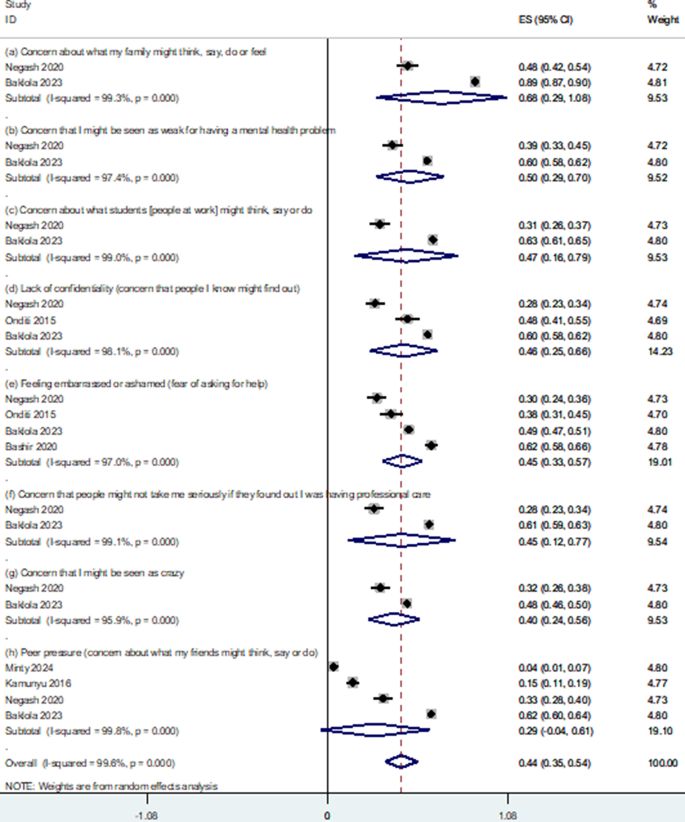

Stigma-related barriers to access of MHSS – Eight types of stigma-related barriers were identified, with meta-analyzable data obtainable from six studies (3,531 students): (a) concern about what family might think, say, do, or feel; (b) concern that one might be seen as weak for having a mental health problem; (c) concern about what students or people at work might think, say, or do; (d) lack of confidentiality (concern that people known might find out); (e) feeling embarrassed or ashamed (fear of asking for help); (f) concern that people might not take one seriously if they found out one was having professional care; (g) concern that one might be seen as ‘crazy’; and (h) peer pressure (concern about what one’s friends might think, say, or do e.g. friends might think less of one). The pooled proportion of students citing these eight barriers was 44% (95% CI: 35%-54%) (Fig. 7). In addition, in one study [49], four stigma-related barriers were cited: not wanting a mental health problem to be on one’s medical records (63.5%); concern that it might harm one’s chances when applying for jobs (58.7%); concern that one might be seen as a bad parent (49.3%); and concern that one’s children may be taken into care or one may lose access or custody without one’s agreement (47.1%).

Forest plot of pooled proportion of students citing stigma-related barriers to access of mental health services or support (based on random effect models with 95% confidence interval)

Utilized sources of MHSS and associated factors

Access to MHSS does not necessarily translate to MHSS utilization: “We know that having help or support resources is one thing, and the utilization of the existing help resources is the most essential and important thing in addressing stress (p.100).” [24] Thus, in this review, the extent to which students utilized different sources of MHSS was measured by the proportion of students receiving treatment [22], adhering to treatment [55], utilizing services [22], [24], or attending intervention sessions [55]. As with accessibility, a higher proportion of students utilized informal sources of MHSS than formal sources.

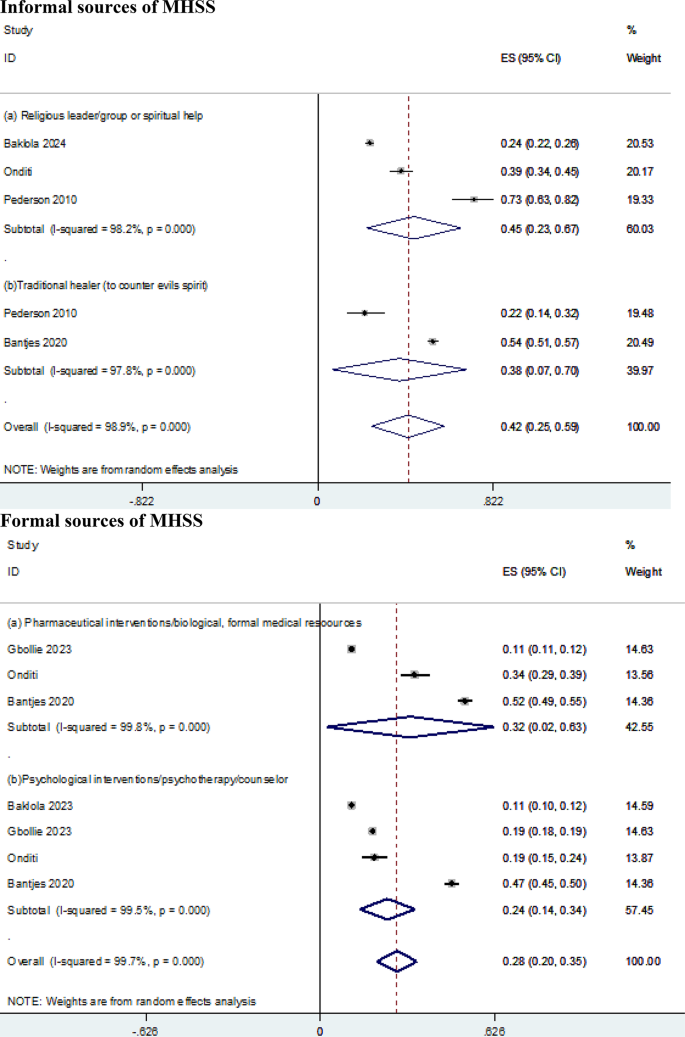

Utilized informal sources of MHSS – This review identified two utilized informal sources of MHSS: (a) religious leader/group or spiritual help and (b) traditional healer (to counter evil spirits). Using meta-analyzable data from four studies, which included 22,790 students, the overall pooled proportion (estimated using a random effects model) of students utilizing these two informal sources of MHSS was 42% (95% CI: 25%-59%) (Fig. 8, upper panel). Other studies identified several utilized informal sources of MHSS. A study exploring the level of utilization of college help or support resources among undergraduate student teachers experiencing psychosocial stressors identified [24]: friends (61%), student union (36%), lecturers (35%), dean of students (33%), academic advisor (28%), and administrative staff (28%). According to a study examining healthcare utilization among first-year university students in South Africa [22], the proportion of students utilizing MHSS were grouped into three categories: type of mental disorder (bipolar spectrum disorder – 64.3%, drug use disorder – 55.8%, generalized anxiety disorder – 36.1%, and major depressive disorder – 36.1%); number of disorders (exactly one disorder – 22.7%, exactly two mental disorders – 30.2%, and three or more mental disorders – 47.9%); and suicidal thoughts and behaviors (suicidal ideation without plan or attempt – 25.4%, suicidal plan without attempt – 41.6%, and suicide attempt – 52.9%). In one mixed methods study [55], good treatment adherence was reported, whereby virtually all students completed all eight treatment sessions, with two-thirds (67%) of them rating the quality of intervention received as excellent. Some qualitatively expressed their satisfaction: “…the care that I received is like [changing a dried tree to a tree with wet leaf]. I received my previous identity; I am confident, strong, have a good communication with my friends.” For some, the treatment received was beyond expectation: “When I came to this office, it was because of my friend’s advice. I was not expecting to get such kind of service. I just came to tell my [internal turmoil] if somebody is ready to listen to me. However, what I was thinking was completely different from what I received. It is beyond my expectation.” In a study examining mental healthcare utilization among first-year university students in South Africa, it was found that despite having access to free student counselling services on campus, less than one-third (28.9%) of first-year students with common mental disorders utilized MHSS in the preceding 12 months [22]. In a study exploring mental health stigma among university students in Nigeria [52], only 13% of students sought immediate medical care for active suicidal ideation. Onditi and colleagues [24] found that only about one-third (36%) of students used the student union as a source of help.

Forest plot of pooled proportion of students utilizing formal (upper panel) and informal (lower panel) sources of mental health services or support (based on random effect models with 95% confidence interval)

Utilized formal sources of MHSS – Two utilized informal sources of MHSS were identified: (a) pharmaceutical/biological intervention or formal medical resources, and (b) psychological interventions, psychotherapy, or counseling. Using meta-analyzable data from four studies, which included 22,790 students, the overall pooled proportion (estimated using a random effect model) of students utilizing these two formal sources of MHSS was 28% (95% CI: 20%-35%) (Fig. 8, lower panel). Several other utilized formal sources of MHSS were reported. Two studies explored the use of digital mental health solutions. A study examining the level of interest in using electronic mental health among Egyptian university students reported the following as reasons for using the Internet as a source of web-based mental health help [58]: convenience (95.6%), user-friendly (85.4%), privacy (84%), rapid response (79.5), cost-effective (79.1%), decreased stigma (74.8%), anonymity (72.7%), and interactivity (59.4%). A study exploring university students’ attitudes towards and perceptions of digital mental health solutions [59] established that 68.5% of students have used the Internet to find information about physical and mental health problems, 9.2% have consulted a mental health professional using an online video conferencing platform, 12.4% have experience of using mental health applications (apps), 4.5% have made use of mental health chatbots.

Factors associated with utilization of MHSS – in one study [22], factors related to utilization of MHSS were categorized based on sociodemographic, types of mental disorder, suicidal thoughts and behaviors, and other factors. Multivariate analysis results showed that female students were more likely to utilize MHSS than their male counterparts (aOR = 1.75, 95% CI = 1.27–2.42) and students with atypical sexual orientations were more likely to utilize MHSS compared to those with typical sexual orientations (aOR = 1.55, 95% CI = 1.04–2.33). First-generation students (neither of their parents had completed tertiary education) were less likely to utilize MHSS than were second-generation students (either or both parents held a university degree) (aOR = 0.29, 95% CI = 0.13–0.64). We found that more female than males students utilized counseling services, 92% versus 9%. With regard to type of mental disorder, the odds of MHSS utilization were as follows: bipolar spectrum disorder: aOR = 4.07, 95% CI = 1.10–15.1; drug use disorder: aOR = 3.45, 95% CI = 1.53–7.80; generalized anxiety disorder: aOR = 2.34; 95% CI = 1.42–3.86; and major depressive disorder: aOR = 1.88; 95% CI = 1.10–3.21, net of other variables in the model. The odds of mental health utilization increased with severity of suicidal thoughts and behaviors: suicidal ideation without plan or attempt: aOR = 2.00, 95% CI = 1.32–3.03; suicidal plan without attempt: aOR = 3.64, 95% CI = 2.44–5.43; and suicide attempt: aOR = 4.57, 95% CI = 2.05–10.2). Another factor associated with mental health utilization was the suitability of the location or environment in which the service was provided. For example, in one study, participants lauded the environment: “Our study was conducted in a building where a student’s general medical clinic is located, so students are not seen to be attending a mental health clinic. This potentially minimized stigma and increased the likelihood of attending the IPT-E sessions regularly (p.10)” [55].