By Michelle Crouch

Co-published with The Charlotte Ledger

When Steve Hardman of Charlotte checked in to see a Novant Health sleep doctor earlier this year, the receptionist handed him a survey to fill out.

Hardman, 66, had seen the questions before — Do you feel safe in your house? Can you afford food? He spent a few minutes checking off the answers and handed the form back to the front desk.

A few weeks later, the bill arrived, and it included an extra $8 fee he hadn’t seen before.

Thinking it must be a mistake, Hardman called Novant’s billing office. The billing representative told him the fee was connected to the questionnaire he had completed.

Hardman was shocked, especially since no one at Novant had talked to him about the survey or his responses.

“You are asking people if they feel safe, if they can afford food. Then you charge them,” he said. “In what world does that actually make sense?”

He said it sounded like a strategy to boost revenue: “It’s only a small amount, but you multiply that by I-don’t-know-how-many patients — probably millions every year — and that’s a nice add to the bottom line.”

A national trend

Across the country, hospitals have started charging for self-administered questionnaires — brief surveys that screen for depression, food insecurity, domestic violence or other risks, said Caitlin Donovan, senior director at the Patient Advocate Foundation, a patients’ rights nonprofit.

The screenings are supposed to flag patients who need extra support, but many people don’t learn about any potential fees until the bill arrives.

Donovan said she has talked to patients from multiple states frustrated that they were billed for checking a few boxes. She said it’s part of a broader billing trend her organization has noticed of health care systems billing for items that used to be included in the visit, whether it’s a facility fee or a charge for messaging your doctor.

“They’re screening for mental health or safety, and that’s incredibly important, but it should be part of the fee for the visit, not an add-on,” Donovan said. “They know if it’s a small-enough amount, most people probably just pay it.”

Novant: Surveys help patients

When asked about the charges, a Novant Health spokesperson said in an email that the survey asking about safety, housing and food security became a billable service in 2024.

“Social determinants of health assessments uncover non-medical factors affecting well-being, connecting patients to social workers, community health workers, and local resources as appropriate,” she wrote.

For example, she explained, patients facing food insecurity are connected to food resources and, if it’s urgent, provided with an emergency pack that includes a four-day supply of food. To date, Novant Health has provided nearly 16,000 emergency food packs, according to the email.

The hospital said most insurance providers cover the assessment, “and the majority of patients pay between $5 and $10.”

UNC Health and Cone Health do similar screenings, but do not charge separately for them, according to spokespeople at each hospital. Other North Carolina health care systems queried by the Charlotte Ledger/NC Health News did not respond in time for publication.

Different types of assessments

After Hardman posted about his experience on the NextDoor site, more than 153 people commented, including some with similar experiences.

“I was billed by them as well,” one woman wrote. “They charged my insurance company for their part and me the balance.”

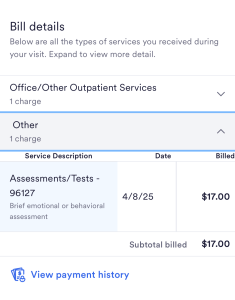

Another shared a photo of a bill with a $17 fee and said, “They just asked the standard questions: Are you depressed? Have you had suicidal feelings?” she said. “And all of a sudden there is a charge for it without any warning.”

Donovan said providers can bill for several different types of assessments. Some screen for so-called “social determinants of health,” like food and housing insecurity. Others screen for mental health problems like depression or anxiety.

Research shows mental health screening surveys can lead to earlier detection of mental health issues and more timely interventions. A 2022 study published in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry found that routine use of brief screenings in primary care settings increased the identification of depression and anxiety disorders by 35 percent, leading to faster treatment initiation and improved outcomes.

Novant said in a statement that its emotional health assessment “plays a key role in identifying early signs of emotional or mental health concerns, allowing for timely support and intervention.”

Nearly 27 percent of patients who take the assessment screen positive for a mental health condition, the hospital said, “underscoring the importance of this screening and the care team’s follow-up.”

“How was I supposed to know about the charge?”

Heidi Bass, 59, of Charlotte agrees the screenings are valuable, but she said what’s missing is transparency.

The $17 charge on Bass’ medical bill

The $17 charge on Bass’ medical bill

She said she discovered a $17 charge for a “brief emotional and behavioral health assessment” only after clicking through several screens to get a detailed breakdown of the bill for her annual physical at Novant earlier this year.

When she called to ask what the fee was for, she talked to several employees before one finally told her it was tied to the questionnaire she completed during the online check-in process.

“When I protested, they said, ‘You don’t have to fill it out.’ But how was I supposed to know about the charge?” she said. “In no other situations do we do something and only find out afterwards how much it costs.”

Some insurers won’t pay

Medical billing expert Adria Gross, CEO of New York-based MedWise Insurance Advocacy, said Medicare and Medicaid typically cover the cost for the screenings.

But some commercial insurers may decline to pay a separate fee because they expect such screenings to be “bundled” into the overall visit charge, she said, which means the additional cost would get passed along to the patient.

“Insurers will also deny payment if the screening is done too often or without documentation that someone reviewed the results,” she said. “It really varies from policy to policy.”

Patients with high-deductible commercial insurance plans may also have to pay out of pocket if they haven’t yet met their deductible.

Gross recommends that patients review their bills, question charges they don’t understand and ask for any they disagree with to be waived.

That’s what Hardman did, and he said Novant dropped the fee once he disputed it.

He already has a plan, he said, if a receptionist tries to hand him a survey at future appointments: “I’ll just decline it.”

This article is part of a partnership between The Charlotte Ledger and North Carolina Health News to produce original health care reporting. You can support this effort with a tax-deductible donation.

This article first appeared on North Carolina Health News and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()