Savannah Kerns, an 11-year-old sixth grader, struggles with social anxiety. Crowds overwhelm her. “I feel like if I get something wrong, people laugh at me,” she said.

Kerns recently transitioned from elementary school to Pleasant Hills Middle School in the South Hills. She’s navigating her class schedule in a larger environment and encountering a wider variety of teachers and students.

Some of those students — “mostly guys from different classes” — bullied her. “Especially because of my weight and style,” said Kerns, who wore an elegant, floor-length black dress while speaking with this reporter in the school’s “Chill Room.” She regularly seeks refuge in the space, which is designed to soothe with soft lighting, abundant plants and nature motifs, including an enclosed seating area built by IKEA decorators to look like a hollowed tree. It’s as wide as a young giant sequoia and can accommodate at least 10 students.

Sixth grader Savannah Kerns poses for a portrait in the Chill Room at Pleasant Hills Middle School on Nov. 20. (Photo by Alex Jurkuta/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Sixth grader Savannah Kerns poses for a portrait in the Chill Room at Pleasant Hills Middle School on Nov. 20. (Photo by Alex Jurkuta/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

This Chill Room is one of 50 in K-12 schools across Allegheny, Washington, Bedford and Erie counties — scaled up from just two when the Allegheny Health Network’s (AHN) Chill Project launched in 2019. The program sets up calming spaces in participating schools that evoke natural environments such as the woods or a bear den (for the Clairton High School Bears).

An AHN behavioral health school educator mans each Chill Room and is trained to work with students while they decompress in the space. The educator partners with school faculty to teach coping skills rooted in cognitive behavioral therapy and dialectical behavior therapy. And an AHN behavioral health clinician provides talk therapy to students and works with a doctor to prescribe medication, if necessary. These staffers work full-time at their assigned school and build trust in the community.

“Some kids don’t really have anyone to talk to or trust,” said Kerns, “and they can come down here whenever they’re feeling upset, angry [or] nervous, and they can talk to whoever’s here.” Behavioral Health School Educator Shelly Meier helped her understand why her peers turn to bullying and referred her to the “Chill Skills” after-school program, which she’s enjoying. “It just makes a big impact on [my] mental health,” added Kerns, who at one point “didn’t want to get out of bed in the morning” and wished to be homeschooled to avoid the bullying.

Chill Project staff say it fills a need for preventive school-based mental health services — a resource that’s sorely lacking in the region, according to Director William Davies. As a result, “we have been able to get in front of some pretty serious actions kids were going to take in harming others,” he said, including “a couple of situations that most likely would have turned into a school shooting.”

Experts foresee a volatile funding environment for school-based mental health services. Federal pandemic relief funding that helped some school districts pay for Chill Project contracts has expired. A 135-day state budget impasse imperiled funding for essential services in Pennsylvania, including an annual appropriation for school safety and mental health services. And the Trump administration’s “One Big Beautiful Bill” will slash Medicaid, which plays a large role in financing school-based health services, said Nirmita Panchal, a KFF senior policy manager and an expert on Medicaid and the Affordable Care Act.

Davies expects the Chill Project will remain stable due to its diversified funding streams, which include clinical services billable to insurance and AHN’s “strong philanthropy department.”

Children ‘suffering and dying’ in schools

The Chill Project is the brainchild of Davies, who saw children “suffering and dying” in or near schools in his previous role managing child and adolescent ambulatory services at UPMC Western Psychiatric Hospital.

He realized that mental health services in local schools were based on “antiquated,” “reactive” models that don’t prevent crises. Health systems similarly require kids to meet a clinical threshold to get diagnosed and treated, and to have insurance that covers the bill. “There isn’t anything preventive going on mixed with very high student-to-school-counselor ratios,” said Davies, calling those conditions “a recipe for disaster.”

He decided to act after five kids died by suicide and five more from gun violence in recent years across two Allegheny County school districts, one affluent and one underserved. (Davies asked Pittsburgh’s Public Source not to name the districts to protect the privacy of the students and their families.) He pitched his idea to Doug Henry, vice president of psychiatry and behavioral health at AHN’s parent company Highmark Health, who helped him conceptualize the Chill Project.

“There isn’t anything preventive going on mixed with very high student-to-school-counselor ratios … [That’s] a recipe for disaster.”

william davies

The first two Chill Rooms — at Pleasant Hills Middle School and Baldwin High School — were funded by the Jefferson Regional Foundation and the Jewish Healthcare Foundation.* Davies said the latter “was very interested” in the Baldwin-Whitehall School District because Robert Bowers — who shot and killed 11 congregants at the Tree of Life Synagogue in the deadliest antisemitic attack in U.S. history — was a student in its system.

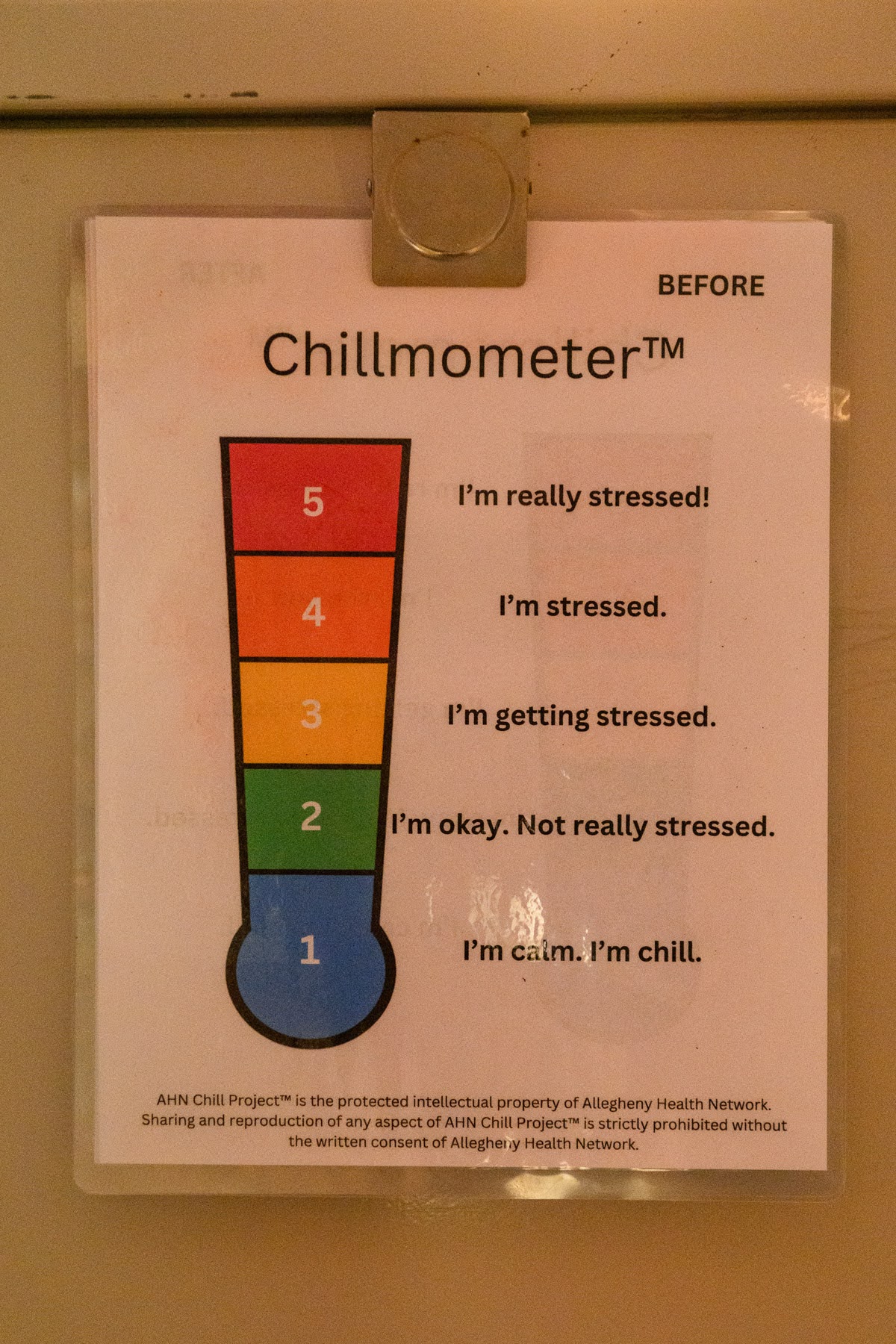

A “Chillmometer” used to help students quantify their emotions in the Chill Room at Pleasant Hills Middle School on Nov. 20. (Photo by Alex Jurkuta/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

A “Chillmometer” used to help students quantify their emotions in the Chill Room at Pleasant Hills Middle School on Nov. 20. (Photo by Alex Jurkuta/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

It’s the kind of tragedy that Chill Project staff are working to prevent through the program’s mission: bridging the gap between a large health system and school districts ill-equipped to meet the “modern mental health needs” of their students, Davies said.

“I don’t feel like we were meeting” those needs, said Daniel Como, principal of Pleasant Hills Middle School in the affluent West Jefferson Hills School District. The school — which had 819 students in the 2024-25 school year — had just one guidance counselor for years. “It was overwhelming for her,” said Como, though “she never complained.” The school hired a second counselor this year. (Pennsylvania’s student-to-counselor ratio during the 2023-24 school year was 319-to-1, according to the American School Counselor Association. That’s higher than the group’s recommended ratio of 250-to-1.)

Como, a Pleasant Hills administrator since 2003, remembered when just “six or seven kids were in school-based therapy.” He said the Chill Project spurred “a huge turnaround” in the number of kids receiving services.

Mackenzie Forsythe is the Chill Project’s full-time behavioral health clinician at Pleasant Hills. Trained as a licensed clinical social worker, she treats about 40 patients at the school. Of those, 18 to 25 attend weekly therapy sessions while others see her less frequently because of the progress they’ve made. She helps kids manage depression and anxiety, and facilitates testing for autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder if she or a teacher suspects a child is neurodivergent. Some cases are more serious: “There are suicidal ideations that are happening,” she said. “There’s depressive feelings and self-injury.”

Learning ‘Chill Skills’

“What … are some physical things that can happen to us when we’re stressed?” Meier, the behavioral health school educator, asked a group of seventh graders during their weekly Chill Skills lesson.

“I slam my head … and get a headache,” one student said after gentle prodding from seventh-grade teacher Naomi Beres. “I start fighting the anger,” said another. “I like this!” the first student called out, enjoying the open dialogue about a topic that many adults downplay or avoid altogether.

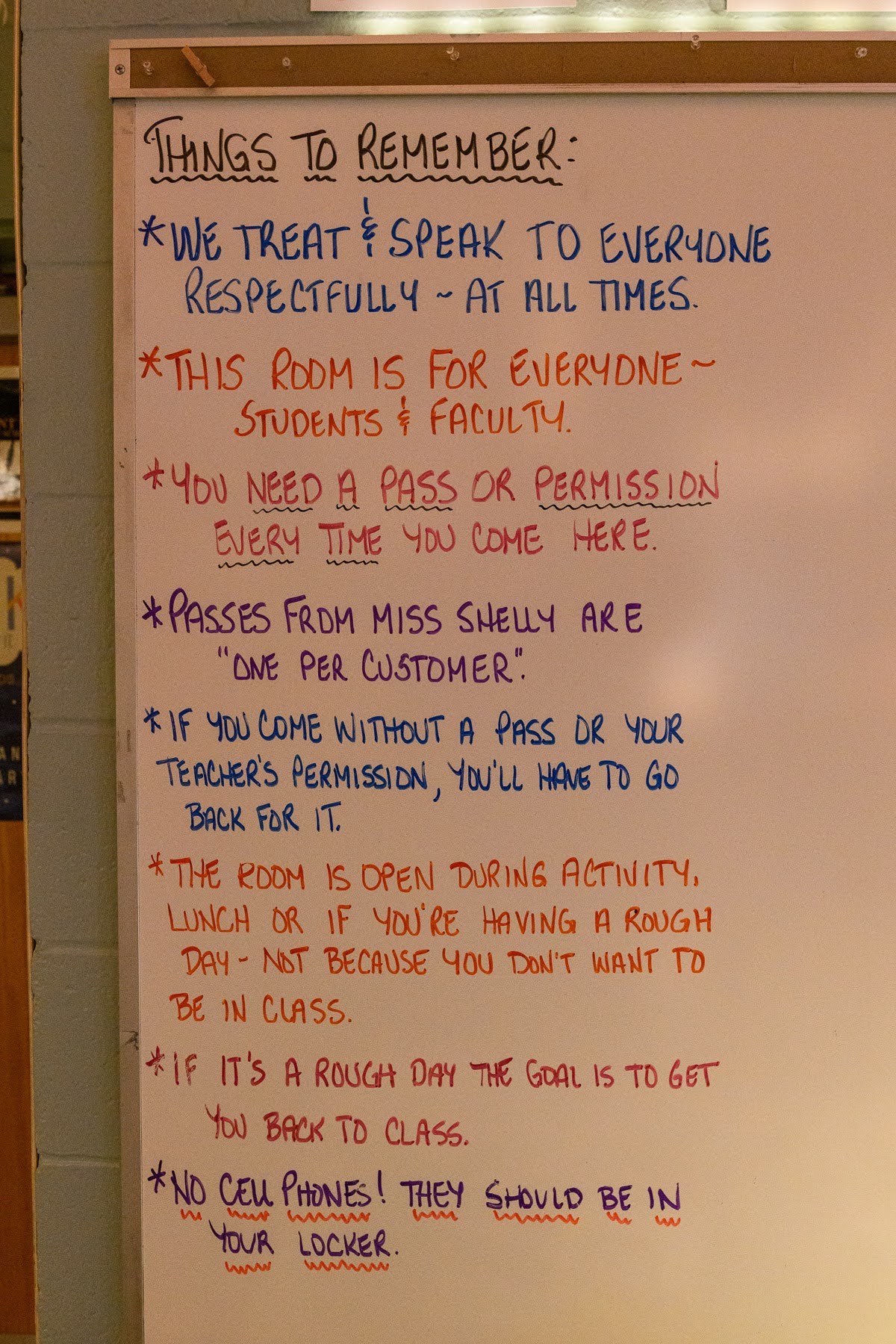

A white board outlining expectations for students in the Chill Room at Pleasant Hills Middle School on Nov. 20. (Photo by Alex Jurkuta/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

A white board outlining expectations for students in the Chill Room at Pleasant Hills Middle School on Nov. 20. (Photo by Alex Jurkuta/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Meier used a flat-screen TV to run through a slide deck on mindfulness, defined as “paying attention to our thoughts, feelings, body sensations and surroundings in this present moment.” She walked the kids through mindfulness exercises for stress relief, such as breathwork and the 5-4-3-2-1 technique. And she guided them through mindful eating of a Hershey’s kiss, which taught them how to become attuned to their senses and practice self-control.

“If you’re feeling stressed and you don’t know what to do, you can come here,” she told the students. “You can take a mindful break.”

Some might object to students missing class, but Meier said Chill Room time is structured to minimize long absences. If a student needs time in the room, their teacher will issue a digital hall pass that alerts Meier. As soon as they walk in, she has them fill out a “thermometer” form to gauge their stress level from 1 to 5. They’ll do so again before leaving the room.

Kids have their pick of cozy nooks in the space. Most are drawn to the tree, but some choose the couch in front of an electric fireplace or an armchair in “the Chill Corner.” They settle in and talk to Meier, who’ll use evidence-based techniques to help them deal with their problem. “You never know what you’re going to get” while listening to a student, she said.

There’s no time limit in a Chill Room, but Meier tries to make the student feel comfortable enough to return to class as soon as possible. The average visit to the rooms lasted just over 12 minutes during the 2024-25 school year. Surveys show a statistically significant reduction in students’ perceived emotional distress after they spend time in a room, Davies said. Meier logged 340 student encounters in the Pleasant Hills room in October. The average thermometer reading was 3 on arrival. It dropped to about 1.7 when students left.

Rising need and funding woes

Clairton City School District is just a 15-minute drive from West Jefferson Hills, but they’re separated by deeply entrenched racial and economic fault lines. In a 2016 report, the defunct nonprofit EdBuild ranked the border between the two districts as the fourth-most economically segregating in the country. While West Jefferson Hills has a “healthy property tax base and can mostly self-fund its schools,” Clairton “can only raise half as much from local taxes,” the report found.

Clairton relies on the state to fund 73% of its budget.

Gov. Josh Shapiro’s original budget proposal earmarked $111 million statewide for school safety and mental health services in K-12 schools — down from $120 million in the 2024-25 budget.

Some legislators pushed to preserve the allocation during the budget impasse. State representatives Eric Nelson, R-Hempfield, and Mike Schlossberg, D-Lehigh County, who co-chair the House Mental Health Caucus and co-authored an op-ed in the Tribune-Review arguing for school mental health funding, both told Public Source that the issue is a top concern among school superintendents in their districts.

“It’s the number one problem,” said Schlossberg, who is also the house majority whip. “That’s literally what I hear — more than safety, more than concern about out-of-school activities, more than school construction.”

Kids in Nelson’s Westmoreland County district tend to live in rural areas where the barriers to mental health care are higher due to lack of transportation or long travel distances to providers. “Their parents just can’t get to the therapy office after school,” he said, noting superintendents told him that school-based services are often a child’s only access point for mental health support.

Eighth grader Ava Bogard sits in the Chill Room at Pleasant Hills Middle School on Nov. 20. Bogard, 13, regularly spends time there during lunch. The space offers relief from the pressure she’s under as a neurodivergent student, basketball player and track and field athlete. She loves to participate in the Chill Project’s “Random Acts of Kindness” challenge, in which students accumulate points for the nice things they do for others. They can spend those points in the “Chill Shop,” which offers snacks, stickers, temporary tattoos, stress balls and more. (Photo by Alex Jurkuta/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Eighth grader Ava Bogard sits in the Chill Room at Pleasant Hills Middle School on Nov. 20. Bogard, 13, regularly spends time there during lunch. The space offers relief from the pressure she’s under as a neurodivergent student, basketball player and track and field athlete. She loves to participate in the Chill Project’s “Random Acts of Kindness” challenge, in which students accumulate points for the nice things they do for others. They can spend those points in the “Chill Shop,” which offers snacks, stickers, temporary tattoos, stress balls and more. (Photo by Alex Jurkuta/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

When the impasse finally ended on Nov. 12 with the passage of a budget, the school safety and mental health number in the final budget was $100 million.

Clairton was hit hard by the budget stalemate.

“That was going to be super problematic for a minute,” Davies said, noting the district had to take out a private loan to continue operations last month due to the state’s four-month failure to make payments. Clairton can’t pay AHN nearly as much as West Jefferson Hills can for its services, Davies added, so the Chill Project raised enough in donations to sustain program operations there.

School-based mental health services play a crucial role in helping students from districts like Clairton overcome barriers to care, said Panchal, the KFF expert. Kids of color and those from low-income households face higher risks of both mental and physical illnesses, and not having access to health services.

Panchal co-authored an analysis of the national landscape for school-based mental health services. It found that nearly one in five public school students receive mental health services in school, with 58% of schools reporting rising demand. There was also a 61% jump in staff concerns about students’ mental health struggles — including trauma and emotional dysregulation — from the 2023-24 school year to the 2024-25 one.

Amid rising need, the Trump administration is trying to dismantle the U.S. Department of Education — a conduit for billions of dollars in federal aid to state and local education agencies, which is then funneled to school districts. (Experts and advocates say the move is illegal without congressional approval.) The administration also announced in April that it would cancel $1 billion in Biden-era school mental health grants, made possible by the most significant anti-gun violence bill in decades.

“Schools are taking some new approaches to addressing mental health needs,” said Panchal, holding up Chill Rooms, mental health days and the integration of social and emotional learning into classroom instruction as examples. But “we are seeing these different federal actions … that could ultimately negatively impact how schools are able to support these services for their students.”

Behavioral Health Educator Shelly Meier teaches a class in the Chill Room at Pleasant Hills Middle School on Nov. 20. (Photo by Alex Jurkuta/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Behavioral Health Educator Shelly Meier teaches a class in the Chill Room at Pleasant Hills Middle School on Nov. 20. (Photo by Alex Jurkuta/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Kerns, the sixth grader, thought about kids who don’t have access to Chill Rooms and other school-based mental health services. Asked if she thinks these resources should be available to all students, she said, “I think they should.”

Venuri Siriwardane is the health and mental health reporter at Pittsburgh’s Public Source. She can be reached at venuri@publicsource.org or on Bluesky @venuri.bsky.social.

*The Jewish Healthcare Foundation has contributed funding to Public Source’s health care reporting. Jefferson Regional Foundation provides funding to Public Source.

This story was fact-checked by Rich Lord.

This article first appeared on Pittsburgh’s Public Source and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()