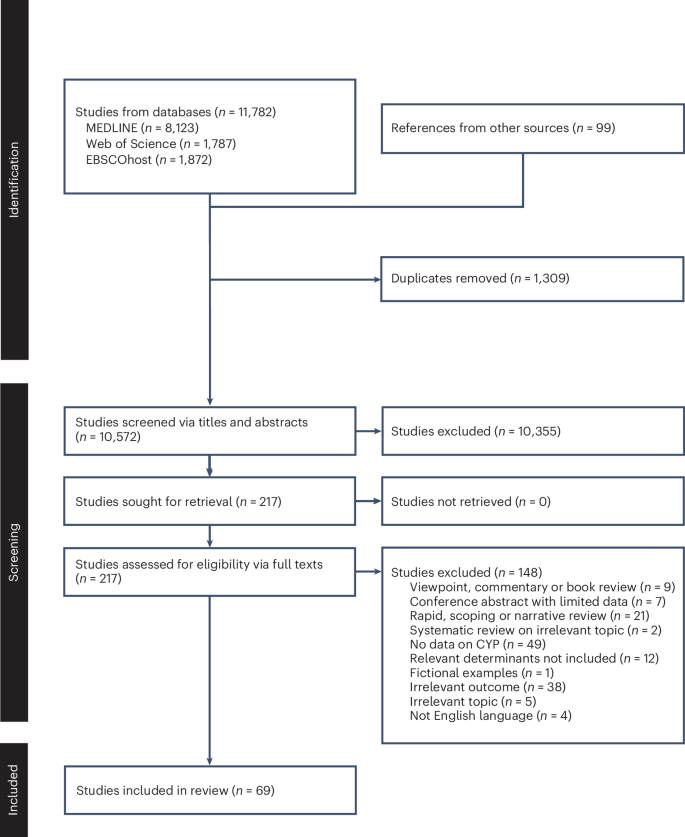

Study selection

The database searches yielded a total of 11,782 results. Ninety-nine articles were also identified from other sources (for example, citations and gray literature searches). After removing 1,309 duplicates, 10,572 titles and abstracts were screened for inclusion. Following title and abstract screening, 217 articles were screened using the full texts. Ultimately, 69 met the eligibility criteria after excluding 148 full texts (Fig. 1 provides full details of the search process and reasons for exclusion).

Fig. 1: PRISMA flow diagram of study selection.

A total of 10,572 articles were screened via titles and abstracts, 217 full texts were assessed for eligibility and 69 met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review.

Study characteristics

Sixty-nine articles were included in the systematic review (summarized in Table 1). All selected studies were published between 1995 and 2025, with a notable increase from around 2021. There were 42 quantitative, 16 qualitative and 11 mixed-methods studies. Of the quantitative studies, most were cross-sectional, with only 2 studies identified as longitudinal47,48. The sample size included within studies varied from 7 participants in a qualitative study examining eco-anxiety experiences and coping strategies49, to 139,941 in a cross-sectional study of Norwegian school pupils50. In terms of geographic location, there was a higher representation of countries from the Global North such as Australia, the United Kingdom (UK), Canada, Sweden and the USA compared with those from the Global South. Only two studies that focused on a single country were identified from Africa, these were from Tanzania51 and Kenya52. Only one study was identified concentrating on a country from Southeast Asia, which was based within the Philippines53, and very few were from East Asia (China54) and South America (Brazil55). Among the cross-national studies included, again the Global South was underrepresented, with the USA and European countries, in particular the UK, represented in the greatest number of studies21,56,57,58.

Table 1 Summary of included studies

Study quality was variable, with the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) checklist score ranging from 0 to 5, with an average of 3 (full results of the quality appraisal can be found in Supplementary Table 1). Across all studies, most adopted convenience, snowball or quota sampling, which are likely to have a high risk of bias. A few quantitative studies included samples that were believed to be nationally representative of the general population, based on probability sampling21,50,59. The absence of a standard measure of eco-anxiety led to a variety of measurement approaches being implemented within quantitative studies. Among 26 studies that included a validated scale, the HEAS27, the CCAS17, the Climate Change Worry Scale (CCWS)22 and the Climate Distress Scale (CDS)60 were used. Most used the CCAS53,54,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75 and the HEAS76,77,78,79,80,81, with a few using the CDS77,82 and the CCWS83,84,85. In other studies, which tended to be older studies published before validated measures were developed, the authors created their own questions86,87, which were often simple single-item measures. A notable trend was the use of online methods for data collection, both for surveys and qualitative interviews, perhaps reflecting that data collection for many recent studies tended to take place during or after the COVID-19 pandemic period. Most quantitative studies involved survey data collection, with a few analyzing secondary data of an existing dataset21,47,51,88. A couple of studies included an experimental component that tested the effect of media exposure on eco-anxiety54,71. A notable limitation across all studies was the lack of ethnic diversity and inclusion of Indigenous groups56,79,85,89, as well as the over-representation of people from more advantaged socioeconomic backgrounds55,79 and young women71,74,82,90,91,92,93.

Among the qualitative and mixed-methods studies, data were collected via focus groups55,56,70,93,94, in-depth interviews49,61,70,78,85,89,91,95,96,97,98,99,100,101, open-ended survey questions74,79,82,90,102, participatory action research66,103, auto-photography91, diary80,104, drawing96,104, participant observation104 and Q sorts70 methods. Particular limitations concerning the mixed-methods studies were the small sample size of the quantitative components61,79, and the lack of analysis of the divergencies and inconsistencies between the quantitative and qualitative findings. The qualitative studies included also sometimes lacked detail on their analysis approaches89,98,103.

Synthesis of findings

The analysis identified several themes within the three categories of determinants contributing to experiences of eco-anxiety, but studies varied in methodological quality (Table 2 and Supplementary Table 1). Social determinants included factors such as age and developmental stage, gender, media exposure, intergenerational relations, peer and cultural norms, and socioeconomic context. Political determinants encompassed government and institutional inaction, distrust, and individual political views, actions and participation. Geographic determinants captured the influence of place-based experiences, including direct exposure to environmental hazards, cross-country differences, and urban–rural distinctions. Each overarching set of determinants is discussed in detail below (further details in Supplementary Table 2).

Table 2 Subthemes within the categories of social, political and geographic determinants of eco-anxietySocial determinantsAge and developmental stage

Age and developmental stage were noted as key predictors of eco-anxiety among CYP. A consistent pattern emerged across multiple studies whereby levels of eco-anxiety tended to increase as age increased into young adulthood. Several studies documented that older adolescents and young adults often engage more deeply with climate issues, with this engagement intensifying as their cognitive and emotional capacities matured87,95,102. This pattern was reinforced within longitudinal studies, which demonstrated an age-related increase in climate worry from 15 to 21 years, indicating that as individuals aged, their perception of environmental threats became more acute48. The 8-year longitudinal study conducted by Sciberras and Fernando found that as age increased from 10–11 years up to 18–19 years, increasing levels of climate worry were observed47. Similarly, in their longitudinal study, Prati et al. observed that climate worry increased from age 15 years to around 23–25 years, after which a small decrease was observed48. In a mixed-methods study focusing on Swedish children and young adults, Ojala noted climate worry was stronger among adolescents (aged around 16–17 years) and young adults (aged around 20–25 years), compared with children (aged around 11–12 years)102. Metsäranta found that eco-anxiety was experienced more strongly among people aged 24–29 years compared with those aged 15–23 years in a sample of Finnish young people105. Similar findings were also observed by Prencipe et al., who found that older youth (aged 23 years) in Tanzania reported the highest levels of climate distress51, and by Donati et al. who found that climate worry was higher among older adolescents than younger adolescents in Italy84.

However, a cross-national study across 23 countries mostly in Europe found little difference in climate worry between age groups21, but differences between countries were not explored. In a Norwegian study of people aged 13–19 years, those aged 15–16 years were more likely to be worried about climate change, but the relationship with age was nonlinear, decreasing among those aged 18–19 years50. In a qualitative study by Chou et al., the authors noted that children aged around 11–12 years may experience more climate distress compared with younger children as they develop and become more able to envisage a hypothetical future55. These results suggest that eco-anxiety may not be uniformly distributed across age groups, but may instead be shaped by psychological development, marking adolescence as a particularly critical period.

Gender

Consistent gender differences in the experience of eco-anxiety were found, with most studies suggesting that young women and girls express higher eco-anxiety levels compared with other genders21,50,51,52,59,67,83,84,87,88,106,107,108. Leonhardt et al. found that adolescent girls were more likely to experience eco-anxiety than boys: 14% of girls reported being very worried about climate change, compared with 7% of boys, and 28% of boys reported being not worried at all, compared with 10% of girls, in their study including 128,484 Norwegian participants50. In their logistic regression models adjusted for sociodemographic factors and leisure activities, girls had 2.60 (95% confidence interval, 2.53–2.67) higher odds of eco-anxiety compared with boys, and this association persisted after further adjustment for mental health and health behaviors50. In a study including 2,652 high-school pupils in Kenya, young women were more likely to report being afraid of climate change compared with men (42.3% compared with 33.8%)52. This gender disparity was also found within several other studies, with a few exceptions.

Comparing climate activists with non-climate activists in Turkey, Ediz and Yanik found no notable differences in climate anxiety between genders69. Hill-Harding et al. found no apparent differences between genders for most results in their study of students at a large UK university74. However, overall findings suggest gender differences in eco-anxiety emerge early and generally persist across developmental stages and different country contexts. Parsons et al. found that even among a relatively gender-progressive country, young women in New Zealand often felt a greater sense of responsibility for pro-climate action compared with men, which was linked to the general feminization of care practices:

“is the emotional and psycho-social burden[s] of caring [for the environment] and [concern about] climate change falls to a huge extent onto women… [This results in] negative impacts [for me and] a lot of women’s psyches, like carrying this burden. I think about [how I can] help fix [the climate challenges faced by] underprivileged women in other countries as well.” (Izadora, FG1; page 1451 in ref. 93)

Ethnicity, race and migration

Very few studies reported on ethnic differences in eco-anxiety and studies generally lacked adequate representation of ethnic minority groups. One study found that students from ethnic minority groups reported lower levels of eco-anxiety compared with those from the white majority group in a study within English secondary schools106. A Swedish study found no difference in climate worry when comparing people from Swedish and foreign national backgrounds59. A number of studies included people from Māori and other ethnic minority groups in Aotearoa (New Zealand), suggesting these group may be particularly affected by eco-anxiety79,89,101.

Socioeconomic context

Several studies highlighted the socioeconomic context as a potential influential factor for eco-anxiety, but findings differed depending on the aspect of socioeconomic position studied (for example, education level, occupation or income) and scale (for example, individual, parental, household or area level). According to Leonhardt et al., adolescents who perceived their family’s financial situation as good had lower risk of being worried about climate change, compared with those who perceived their financial situation as poor, in the large Norwegian study50. They also found that the level of parental education was consistently associated with eco-anxiety; compared with those with no higher education, young people whose parents had higher education had 1.57 (95% CI, 1.52–1.61) higher odds of being worried about climate change50, which was also found in several other studies, including within Sweden59, Portugal76 and Tanzania51. In a study based in Australia, those living in less advantaged areas (according to the Index of Relative Socio-economic Disadvantage) had higher odds of experiencing eco-anxiety compared with those living in more advantaged areas62. Among UK residents, higher socioeconomic status (measured by the Family Affluence Scale109) was associated with higher levels of eco-anxiety82. However, a study in Poland found that young adults in an unfavorable financial situation had higher odds of experiencing stress related to the climate crisis108.

Chou et al. elaborated in their qualitative study using focus groups with participants aged 5–18 years in three areas of Brazil55 that the socioeconomic context shapes awareness and engagement with climate change:

“There are two types of rich and poor people who deal with this situation: the rich ones either don’t care, they only think about money—or are informed and try to do as much as possible, because they have the money for it. There are two types of poor people, who either have no place to find information—or they have information, but they don’t have money to afford organic food.” (12,F; page 260 in ref. 55)

Furthermore, they found that the groups who were more aware and engaged with climate change issues belonged to the wealthier social classes and experienced more eco-anxiety55. This group comprised children and adolescents whose parents were more engaged in environmental action, or who attended private schools that had climate change integrated into their curricula. The influence of parental occupation was also noted by a participant, who noted that as their mother was a journalist, they felt well informed by them55. Working in extreme temperatures was also linked with climate distress in a Tanzanian study51, but there was a general lack of studies examining occupational influences. Another study highlighted how youth climate activists from privileged backgrounds had greater access to emotional and social resources to navigate eco-anxiety, further highlighting inequality in resilience and response capacity89. Other studies noted the educational context; students enrolled in environment-related courses tended to report higher levels of eco-anxiety67,68,81,98. However, these cross-sectional studies do not imply a causal relationship as students likely self-select based on their concern about the environment.

Media exposure

Media exposure emerged in several studies as a potential determinant of eco-anxiety54,61,67,71,72,75,90,96,97,105. In multiple qualitative studies, increased exposure to climate-related news, especially through social and mass media, was mentioned as a key theme. Studies highlighted that media allow the distribution of helpful information that can inform people about environmental issues95, but it can also intensify feelings of helplessness, especially when messaging is fear-based or lacks hopeful framing57,75. The frequency of media use and attention given to climate change news were key predictors of climate anxiety in a study based in the USA, with media exposure variables explaining around a third of the variance in climate anxiety scores75.

Many studies mentioned social media as an important factor affecting how CYP experience eco-anxiety47,50,61,90. A mixed-methods study by Gunasiri et al. including 46 participants aged 18–24 years in Australia found that negative stories about climate change shared on social media can contribute to feelings of hopelessness, guilt, shame and anxiety, which can be overwhelming61.

“I do get a lot of climate anxiety when I read the stuff about how June was the hottest month, I’m like yeah I can’t do anything about that.” (Interview participant 7; page 6 in ref. 61)

However, social media was also reported to have a positive role, providing a platform for young people’s voices and action:

“You can be speaking to people on the other side of the globe that you’d never interact with at any other point in your life and you’re able to build a community and a network.” (page 7 in ref. 61)

In another Australian study by Sciberras and Fernando, greater societal engagement, including consumption of news relating to international affairs, was related to high and increasing levels of climate worry over time47. A study across eight countries also found that participants reported increased climate anxiety due to social media coverage90. In contrast, the large cross-sectional Norwegian study by Leonhardt et al. found that individuals who expressed higher levels of concern about climate change tended to spend less time using social media50. Despite some variation, the overall pattern suggests that media can act as both a conduit for climate awareness and action, as well as a vector for eco-anxiety.

Intergenerational relations

A few studies indicated that intergenerational relations, including trust in older generations and worry about future generations, are potentially related to eco-anxiety49,56,68,91,94. Boyd et al. highlighted a ‘generational misalignment’, where youth report frustration and distress arising from perceived climate inaction by older generations94. This lack of trust in adults’ willingness or ability to mitigate climate threats contributed to feelings of betrayal and powerlessness among young people with pre-existing mental health problems in Australia94. Frustration at the burden of trying to fix previous generations’ actions was similarly highlighted in another qualitative study based in Quebec, Canada85.

“Yeah, I’m also angry at previous generation because actually, it’s us, it’s us who have to live with this… Like people who are 70 will die in like 30 or 20 years even, you know… it’s me who is 11 years old that will live in 40 years, 50 years, 60 years… Probably I’m going to live that again and again because others who are 70 years old today will have passed away when I’ll be 70 years old… But I will be there, I will see everything that degrades.” (Participant 15, 11 years old; page 10 in ref. 85)

Smith et al. also documented how young women expressed eco-anxiety in the context of contemplating future family planning, citing concerns about the environmental legacy being inherited from previous generations91. These findings suggested that diminished intergenerational trust may contribute to eco-anxiety, with eco-anxiety also relating to life choices which will affect future generations49,68.

“I mainly think about my own children that I want to have in the future […] And, you know, since I feel like they will be close to me because they are my family, I feel like I’m already worried about them. And these children don’t even exist and this future that doesn’t even exist. But it’s something that worries me the most. I think about my future family living in a world with climate change.” (Participant 7, female, 23; page 34 in ref. 49)

Peer and cultural norms

The influence of peer and cultural norms emerged as correlates of eco-anxiety in some studies47,56,86,87. Thomas et al. found that young people often described their climate emotions as shaped not only by personal experiences but also by the social environments in which they are embedded, including peer interactions and broader cultural narratives56. Cultural expectations regarding environmental responsibility, particularly in collectivist or activist-oriented communities, may heighten pressure to respond emotionally or behaviorally to the climate crisis. Sciberras and Fernando reported that individual worry profiles may be influenced by shared social and cultural contexts, where normative beliefs about climate change can either validate or suppress eco-anxiety47. In a qualitative study using participatory action methods, young people also highlighted the stigma surrounding climate concern and the unwillingness to talk about these issues in countries such as Jamaica (where some older people considered extreme weather to be a normal occurrence), but also in the UK (where it has been considered a taboo subject)103. They also mentioned struggling with whether to discuss concerns with family, friends and colleagues. A culture of denial was also found to be a source of eco-anxiety in a small mixed-methods study among adolescents participating in environmental groups at the University of Vermont, Canada97. Being ‘shamed’ by peers, belittled and experiencing derision related to their interest in climate issues was highlighted by several participants in a small study based within a Welsh school:

“I was made fun of and called Greta Thunberg for speaking out loud for defending my opinion. I know for a fact that I am not the first one, and sadly will not be the last one to experience it… I believe that is the school’s duty to stop shaming people for their beliefs and start to give better education.” (Sara, YP5, 2166–2174; page 80 in ref. 66)

Political determinantsDistrust

Studies consistently revealed concern from CYP regarding their lack of inclusion and representation in decision-making processes and their lack of trust in government and institutions, which can exacerbate eco-anxiety58,79,82,100,103,110. The cross-sectional study by Hickman et al. with data from 10,000 young people across 10 countries found that participants felt more betrayal (highest in Brazil, India and the Philippines) than reassurance toward the government, which correlated with climate anxiety and distress58. Barnes found that participants expressed pervasive distrust in government actors, associating this with heightened existential concern and hopelessness about the future98. Similar sentiments were reported by Thomas et al. where US participants described disappointment and anger toward political leaders as intensifying their eco-anxiety56, and in a study focused on Australia exploring CYP’s emotional responses to climate change:

“We have a few more Independent politicians in Parliament now […] so I think that is a positive… I feel more hopeful, but the trust is still low due to the previous government when nothing happened.” (young person, age 24; page 9 in ref. 100)

Other studies further elaborated that CYP often perceive political leaders as unresponsive or indifferent to the urgency of the climate crisis, resulting in frustration, alienation and a diminished sense of agency55,56,66,100,103. These studies suggest that eco-anxiety is not merely a reaction to environmental degradation, but a response to political systems perceived as inadequate or disingenuous in addressing the crisis.

Government and institutional inaction

Government and institutional inaction was identified as a recurring theme contributing to eco-anxiety. The large cross-sectional study by Hickman et al. highlighted that young people’s negative perceptions of governmental responses to climate change were associated with increased levels of distress58. Moreover, government inaction was frequently mentioned to be intertwined with political interests and industry lobbying, exemplified by Myers et al. in an Australian study, which highlighted young people’s frustration and anger as they witnessed fossil fuel industries influencing policymaking and distributing misinformation101. This hindered effective climate action, leading to reduced trust and contributing to eco-anxiety, especially when young people felt that their concerns were being dismissed. These findings were corroborated in another study by Boyd et al.:

“They’re really letting us down, like, [the Prime Minister] is putting so much money towards fossil fuels. When we really need to focus on the environment at the moment, because what’s the point of making money if you’re not going to have a planet? You know those politicians who are meant to oversee the stuff, they’re in their like, 60 s, 70 s. So by the time it actually hits really hard, a lot of them will probably not be here anymore. So it’s a bit discouraging as well. Like, it’s sort of been relegated to us.” (Client8; page 1027 in ref. 94)

Several studies revealed that perceived governmental inaction, lack of transparency and symbolic rather than substantive climate policies erode public confidence and contribute to emotional distress49,55,61,62,78,89,91,94,97,98,103,111. Hill-Harding et al. examined students’ emotional responses to climate change among university students in the UK and also found that perceptions of inadequate institutional responses, in this case, the university, may exacerbate eco-anxiety74.

Individual views, participation and actions

The literature consistently highlighted other political factors that may shape eco-anxiety, including political views and participation. Parsons et al. found that youth engaged in climate activism frequently expressed both empowerment and psychological strain, highlighting the emotional weight of taking on political responsibility when institutional responses are seen as inadequate93. Sciberras and Fernando found that adolescents with consistently high or increasing climate worry were more politically engaged47. Gunasiri et al. similarly found that participants who took climate action reported higher levels of worry, but that there were also positive psychological benefits (for example, feeling more in control)61, and in other studies the development of a social network that validated their identity was highlighted95. Some studies also noted concern around the potential repercussions of protest involvement101. Other studies also noted that a more liberal or left-leaning political orientation was associated with higher eco-anxiety among CYP75,98.

Geographic determinantsDirect exposure to environmental hazards

The direct experience of climate-related events was highlighted in several studies that explored CYP’s personal experiences53,55,61,77,92,101. A cross-sectional study by Vercammen et al. in the USA reported that individuals who had direct experience of climate change impacts (particularly wildfires) had higher mean scores for climate distress and eco-anxiety compared with those who had not encountered such impacts, even when taking into account age, gender, education level, family affluence, urban–rural residence and ethnicity77. The cross-sectional study conducted by Lykins et al. investigated Australian youth mental health in the aftermath of the Black Summer bushfires during 2019–2020, highlighting the mental health impact of localized events related to climate change on the individuals affected directly92. Young people directly exposed to the bushfires experienced higher levels of climate distress and concern compared with those who were not directly exposed. The study found that the proximity of the bushfire event, whether in terms of physical distance, social or temporal aspects, did not appear to have an impact on anxiety levels92. Simon et al. similarly found that young people living in the Philippines, where many people constantly experience first-hand the effects of climate change-related typhoons and droughts, were prone to experiencing eco-anxiety, but this also motivated them to take climate action53.

Qualitative research in New Zealand highlighted the potential impact of living in a coastal community, where one participant saw first-hand the erosion of the foreshore on his journey to school101. Chou et al. also highlighted that having family members impacted by climate-related events, such as flooding, led to feelings of fear among some participants in a qualitative study based in Brazil55. People living in low-lying countries, such as the Philippines and Jamaica, reported experiencing despair that their homelands may cease to exist in the future owing to sea-level rise and flooding103. Hearing the rain was also highlighted as a trigger for eco-anxiety among those affected by flooding in an Australian study focusing on young people with mental health problems94.

“And at night time that rain, for me, it was triggering. It was like, ‘Are we going to be flooded’? You know, I’m safe, but it still doesn’t help you not think about it. Think about others and yeah, animals, wildlife, all those things that are put out of place. I think that affects a lot of people too.” (Client 7; page 1028 in ref. 94)

Cross-country differences

The study by Hickman et al. suggested that the climate vulnerability of regions may be an important geographic determinant of eco-anxiety, with notable cross-country differences58. Surveying 10,000 CYP across 10 countries—including both high-risk and less-affected regions—the study found that youth living in areas more vulnerable to climate impacts (for example, Philippines and India) reported higher levels of climate worry and distress58, compared with countries such as Finland and France. In another multi-country study, Lau et al. explored differences in emotional engagement with climate change including climate anxiety, finding that participants in China had the highest levels, compared with Portugal, South Africa, the UK and the USA57. Other cross-national studies found few differences between levels of climate worry between countries87,112. Differences in measurement and scoring approaches used across quantitative studies made it difficult to synthesize results from single-country studies; therefore, we focused on the multi-country studies (Supplementary Table 3). However, these are also limited by the lack of nationally representative samples.

Urban–rural residence

Potential differences in the manifestation of eco-anxiety were found based on the urban or rural residence of the individual, but findings differed by country. For example, Strife et al. conducted interviews with urban American children who expressed heightened environmental anxiety, influenced by their exposure to urban environmental degradation96. In contrast, studies such as Ndetei et al. suggested that youth living in rural or semi-urban regions in Kenya may experience eco-anxiety differently, with their concerns more closely tied to direct interactions with the natural environment and localized climate impacts52. In this study, young people living in rural areas were found to experience a higher level of climate worry compared with those living in urban areas52. Chou et al. also identified regional disparities in Brazilian children’s climate awareness, emphasizing that urban access to information and activism differed from rural lived experiences55. Adolescents living in urban areas of Norway were more prone to eco-anxiety, compared with those living in rural areas50. Similarly, Prati et al. found living in the Italian countryside to be negatively correlated with climate worry48.