Study characteristics

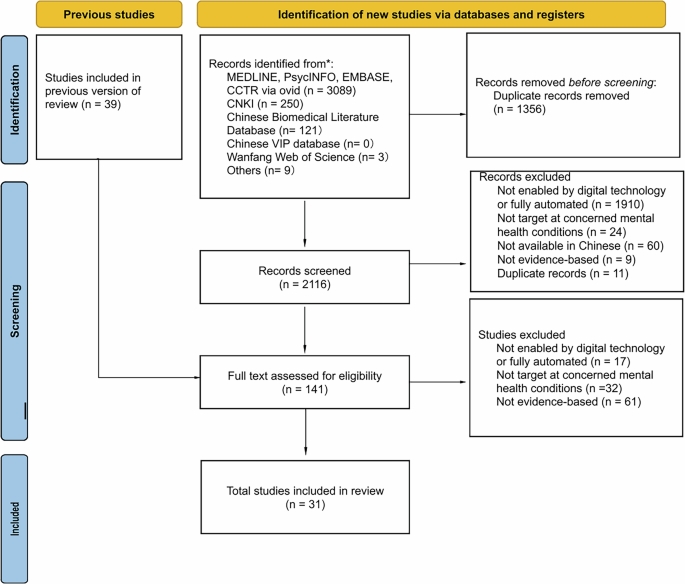

Our literature search retrieved 3472 study records, which were reduced to 2116 after removing duplicates (see Fig. 1). After the title and abstract screening, 102 articles were retained for full-text review. Of these, 89 were excluded, and 13 met the inclusion criteria. Additionally, 18 studies from the previous review on digital mental health in China8 met the inclusion criteria. All full-text records were screened independently by two reviewers (Cohen’s κ = 0.90). In total, 31 publications on 32 trials of 28 unique interventions were deemed eligible and included in the narrative synthesis. One of the included studies reports on three separate trials, two of which met the inclusion criteria16. The collection of included studies involved 24 English-language peer-reviewed studies and 7 Chinese-language peer-reviewed studies.

PRISMA flowchart of studies identified for inclusion in the review.

Table 1 provides an overview of the characteristics of studies included organized by intervention. All 32 trials were conducted in the Greater China region, including nine (28%) in Beijing, six (19%) in Hong Kong, four (13%) in Zhejiang, three (9%) in Guangdong, two (6%) in Shanghai, two in Macao (6%), one (3%) in Shandong, one (3%) in Chongqing, and four (13%) in multiple cities in China. Of the 28 interventions, 17 (61%) were in simplified Chinese, four (14%) were in traditional Chinese, one (4%) was in both simplified and traditional Chinese, and six (21%) were in unspecified Chinese (did not clearly indicate simplified or traditional Chinese usage). Twenty-two (79%) were locally developed for Chinese-speaking populations, six (21%) were originally developed internationally and translated into Chinese. Of the six internationally developed interventions, three (50%) were adapted for the Chinese context. Most interventions 22 (79%) were for adults, and six interventions (21%) were conducted amongst individuals less than 18 years old.

Table 1 Characteristics of the interventions grouped by online intervention modalityOnline intervention modalities

A range of digital technologies were utilized for mental health interventions. Among the 28 identified interventions, 12 (43%) were application-based interventions delivered via mobile devices, highlighting the increasing reliance on mobile technology for mental health support in the Greater China region16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27. Of these, four interventions utilized existing applications as delivery vehicles: two through WeChat22,26, a widely used social media platform in China, and two through WhatsApp16, a popular messaging application. Additionally, one intervention leveraged automated text messages to provide interventions28. Web-based interventions were employed in seven interventions (25%), reflecting the accessibility and broad reach of internet-based programs29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38. There is also a growing interest in immersive technologies for mental health treatment, as evidenced by the seven interventions (25%) that used virtual reality-based interventions39,40,41,42,43,44,45. Zhu et al. developed a computer software program to deliver their intervention, demonstrating a unique approach among the reviewed studies46.

Target population

The interventions included in this review targeted a variety of populations. Four (14%) interventions targeted a broad, non-specific universal sample from the public16,18,25. One study specifically recruited participants from university settings, aiming to represent the academic community32. Additionally, one study recruited a healthy sample of seventh-grade Chinese middle school students26. The remaining 27 trials of 22 unique interventions can be grouped into two categories based on the participants’ health conditions: individuals with existing mental health symptoms and individuals with existing physical health symptoms.

Individuals with existing mental health symptoms

Nineteen interventions (68%) targeted individuals with mental health symptoms. Among these, seven (37%) interventions focused on participants with self-reported depressive symptoms or a formal diagnosis of depression20,21,22,24,34,36,39,41,46. Three (16%) interventions derived from five studies addressed individuals with high social anxiety: one targeting adolescents19, one targeting adults23, and one targeting university students29,31,37. One intervention targeted individuals with situational insomnia35, and another focused on those with generalized anxiety disorder44. Additionally, three (16%) interventions derived from five studies included participants with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD)45, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)30, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)38, respectively. Four (21%) interventions derived from five studies aimed at individuals looking to quit smoking or struggling with impulse control and substance use disorders, including one for tobacco users28, one for internet addiction33, and two for broader substance use issues17,27. Of the 19 interventions, four (21%) were implemented to augment usual treatment, which included psychotropic medication use and psychological counseling27,39,41,46.

Individuals with existing physical health symptoms

Three interventions (11%) focused on individuals with physical health symptoms who were undergoing medical treatments that could have mental health impacts. Mao et al. and Wong et al. tested the effects of VR-based interventions on cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy40,42. Ran et al. applied a VR-based intervention to dental patients between the ages of four and eight to reduce anxiety and pain43.

Target outcomes and intervention typesDepression and related symptoms

Among the 28 included interventions, ten (36%) assessed depression as the primary outcome20,21,22,24,25,32,34,35,36,39,41,42, and another three (11%) included depression as the secondary outcome16,38. Of these 13 interventions, six, originating from five studies, employed mindfulness-based techniques16,24,32,39,42. Three interventions derived from four studies used internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy (iCBT)22,34,35,36. Other interventions included attention training41, behavior activation20,21, self-efficacy38, and a lifestyle medicine approach that incorporated psychoeducation, physical activity, nutrition, stress, sleep management, and motivation components. The severity of depression was measured using scales, including the Hamilton Depression Scale35,39,41,42, Beck Depression Inventory39, Patient Health Questionnaire-916,20,21,22, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale34,36, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale35,42, Symptom Checklist 90-Depression38, and 21-Item Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale25,32. Eleven interventions (85%) demonstrated significant improvements in reducing depression in the intervention group post intervention16,20,21,22,24,25,34,35,36,38,39,41,42, with two demonstrating sustained significance beyond the immediate post-treatment period16,38. Among the nine interventions that reported effect sizes, seven had small to medium effects16,22,24,25,32,38. One behavioral activation-based digital intervention for depression “Step-by-step” showed a large effect in the pilot20 but a moderate effect in the full trial21. One iCBT intervention underwent evaluation in trials conducted by Ren et al. and Yeung et al., where Ren et al.’s trial36 exhibited large effect and Yeung et al.’s trial34 found a moderate effect size for the intervention.

Anxiety

Generalized, mixed, and situational (non-social) anxiety was assessed as the primary outcome in eight interventions (29%)25,26,32,35,40,42,43,44, and five (18%) as the secondary outcome16,20,21,22,24. Among the eight interventions that measured anxiety as the primary outcome, one used relaxation and physical activity26, one employed mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT)42, one adopted mindfulness-based intervention32, two utilized distraction interventions40,43, one implemented exposure therapy44, one used iCBT35, and one took a lifestyle medicine approach25. The severity of anxiety was assessed using the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale26, General Anxiety Disorder 7-item16,20,21,22,24, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale44, and the State Anxiety Scale for Children40. Ran et al. assessed the application of a VR intervention to improve operative anxiety and behavior management during short-term dental procedures among children using the Children’s Fear Survey Schedule-Dental Subscale and Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale43. Additionally, two studies utilized the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale to concurrently measure the severity of depression and anxiety35,42, while two other studies25,32 utilized the anxiety subscale from the 21-item versions of the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale. With one exception, all interventions that measured anxiety as the primary outcome reported significant improvements in anxiety levels post intervention. The exception was an internet-based mindfulness intervention that incorporated principles from the Health Action Process Approach and assessed anxiety using the short version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale32. Additionally, of the eight interventions reporting effect size, seven interventions showed small effects16,21,22,24,25,32, while one had large effects40. The Step-by-Step pilot20 reported a large effect size while the full trial21 reported a small effect.

Social anxiety

Three of the included interventions (11%) focused on social anxiety19,23,29,31,37. These studies used the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale29,31,37, Social Phobia Scale29,31,37, Social Anxiety Scale19, Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale23, and State-Trait Anxiety Inventory23. All three interventions—one web-based cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)31,37 and two mobile-based cognitive bias modification for interpretation19,23—significantly reduced social anxiety. However, one of the three trials examining the web-based CBT treatment only investigated the predictors of treatment adherence and outcomes but did not report the effects on outcomes29. Another one of these three trials reported large effect sizes37. Lin et al. also measured the level of Taijin Kyofusho (TKS), a culturally specific form of social anxiety common in Eastern cultures where individuals worry that their behaviors, expressions, or physical characteristics might offend or discomfort others31, as the primary outcome measure using the 31-item Taijin Kyofusho Scale (TKSS). The study found that participants in the intervention group with higher pretreatment TKS levels showed significant reductions in TKSS scores posttreatment.

Mental wellbeing

Four mindfulness-based interventions (MBI) (14%) assessed general mental health and well-being, two as the primary outcome18,32 and two as the secondary outcome16. All four interventions used the World Health Organization Five Well-Being Scale (WHO-5), a short, self-administered, and positively worded scale that measures subjective well-being over the past two weeks. Wong et al. investigated an intervention based on the lifestyle medicine approach, using the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale – 21 Items to assess overall mental health as the primary outcome measure25. Additionally, the Step-by-step intervention trials conducted by Sit et al.20 and Li G et al.21 measured subjective wellbeing as the secondary outcome using WHO-5. Six interventions16,18,21,25,32 significantly improved mental well-being following the interventions and reported small to moderate effect sizes.

Cognitive function

Four of the included interventions (14%) measured cognitive function as the primary outcome27,30,41,46 and one measured it as the secondary outcome45. These studies evaluated the efficacy of different interventions: a VR-based exposure and response prevention intervention for female OCD patients45, a computer-assisted cognitive remediation intervention for adult patients with major depression46, a web-based executive function training intervention for pediatric ADHD patients30, a mobile-based attention training intervention for pediatric patients with depressive episodes41, and a cognitive training and cognitive bias modification-based intervention for males with methamphetamine use disorder27. Cognitive function was assessed using screening tests including Montreal Cognitive Assessment-Basic45, Wisconsin Card Sorting Test46, Trail Making Test, Stroop Color and Word Test, the CogState Battery27, objective evaluation30, and the Mini Mental State Evaluation Scale41. Four interventions27,41,45,46 significantly improved cognitive function and performance for participants in the intervention group, but no effect sizes were reported in the original articles. Additionally, the web-based executive function training intervention for pediatric ADHD patients did not demonstrate significant effects on executive function based on objective evaluations30.

Sleep

Two interventions, one utilizing CBT35 and one a MBI16, measured sleep-related indicators as primary outcome measures. Four other interventions, one employing relaxation and physical activity26, one using MBCT24, one implementing CBT22, and one adopting a lifestyle-medicine approach25, measured sleep-related indicators as secondary measures. The assessment measures included the Insomnia Severity Index16,22,25,35, Pre-sleep Arousal Scale16,35, Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes about Sleep Scale16, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index24, and the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System26. Both interventions that targeted sleep-related concerns as the primary outcome reported significant improvements in the intervention group post-intervention16,35; of these one reported large effect size16.

COVID-19 related outcomes

Four of the included studies directly addressed pandemic-related mental health challenges. Among these, one CBT-based intervention measured the severity of situational insomnia35, three other interventions examined COVID-19 related depression or anxiety symptoms as the outcome measures22,26,44. Zhang et al. documented three cases of patients with generalized anxiety disorder, who were primarily concerned with COVID-19 infection anxiety and reported that exposure therapy significantly reduced their anxiety levels44. Zheng et al. used an intervention promoting relaxation and physical activity and significantly reduced anxiety and eye strain among Chinese middle school students under home confinement26. Song et al. tested the efficacy of an iCBT intervention on reducing COVID-19 related mental health problems and reported medium effect sizes22.

Others

An expert system intervention for college students with internet addiction found a significant decrease in self-reported hours spent online per week and online satisfaction after the intervention. The intervention was found to have large effect sizes33. Two CBT-based interventions for substance use—one targeting smoking cessation28 and the other for adults with recent substance use17—reported significant improvements in addiction levels following smartphone-based interventions using measures including self-reported cigarette consumption and the timeline follow-back survey on primary drug use. Li A et al. measured eating behaviors with the Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire and the Power of Food Scale after a mindfulness-based intervention with eating-specific exercises and found significant improvements16.

Public availability

Of the 28 interventions reviewed, only one (4%) remained publicly available after the conclusion of the study18. Mak et al. designed the “Living with Heart” intervention, a mobile-based intervention in Hong Kong that offers mindfulness, self-compassion, and cognitive behavioral psychoeducation training for the general public18. The Android mobile version of this intervention is publicly accessible47.

The effective web-based CBT intervention for Chinese depression patients, MoodGYM, was reported by Yeung et al. and Ren et al.34,36. Although originally developed in Australia and translated into Chinese for the studies, only the English and the German version are currently available48. Additionally, the smartphone-based lifestyle medicine intervention developed by Wong et al., to address overall mental health for the general public in Hong Kong is expected to become available later this year25. All other interventions (86%) reported in the reviewed studies are not publicly available.

Study design

According to the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine levels of evidence49, this review included 25 (78%) randomized controlled trials (RCTs), six (19%) quasi-experimental designs, and one case series.

Randomized controlled trials

Six RCTs used an active control group, including four trials with “treatment as usual”27,39,41,46 and two trials as “enhanced treatment as usual”18,21. Three trials used a “no treatment”31,40,43 group. Four trials used attention control by adding components such as mental health education or basic counseling17,24,26,28. Ten trials utilized a waitlisted control group, granting participants in the control group access to the intervention after the trial’s completion16,19,25,32,33,34,36,37,38. Two trials used a mock intervention like the experimental intervention23,30. Among all RCT trials, two employed a three-arm design18,32.

Quasi-experimental designs

Of the six trials that adopted a quasi-experimental design, three employed a non-randomized approach. One trial evaluated cognitive behavioral therapy for COVID-19-related mental health problems, demonstrating its impact on reducing symptoms associated with the pandemic22. The other trials focused on treating social anxiety29 and OCD45 respectively. Additionally, three trials utilized a single group, pre-post uncontrolled design to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions20,35,42.

Case series

One case series study explored the role of virtual reality exposure therapy in treating psychiatric illness in three patients who had chief complaints of fear of COVID-19 infection44.

Quality assessment and acceptance

Quality assessments were conducted using the JBI critical appraisal tools. Results for the 31 publications included in Tables 2–4. While the review includes 32 trials, the quality assessment for the two RCTs from Li A et al., was based on that publication as a whole, resulting in 31 quality assessments16. Among the 24 RCTs reviewed, five (21%) had a low risk of bias21,24,25,26,27, 16 (67%) had a moderate risk of bias16,18,19,23,28,30,31,32,34,40,41,43,46, three (13%) had a high risk of bias17,33,39. Studies with moderate or high bias risk often showed weaknesses in selection, allocation, intervention administration, and outcome assessment methods, primarily due to unspecified randomization procedures or lack of participant and outcome assessor blinding. Due to the nature of psychotherapy interventions, double-blind designs were rarely feasible, with only two studies24,28 employing them. If the blinding of the participants and personnel rating were removed from the assessment, the risk of bias for these eight trials would be reduced significantly16,18,25,32,36,38,40,43. Of the six quasi-experimental studies reviewed, two (33%) had low risk of bias29,45, two (33%) had moderate risks20,22, and two (33%) had high risks35,42, primarily due to issues in selection and allocation, particularly the absence of a control group. The case series study had a high risk of bias as it lacked information regarding inclusion criteria and demographics of the patients.

Table 2 Quality assessments for randomized controlled trials included in the reviewTable 3 Quality assessments of quasi-experimental trials included in the reviewTable 4 Quality assessment of the case series trial included in the review

Additionally, seven interventions (25%) reported the acceptability or satisfaction levels of participants using a combination of questionnaires25, self-designed surveys17,34,38,40,42, and qualitative interviews20,21,40. All seven interventions reported high levels of acceptability and satisfaction among participants, indicating a positive reception and perceived value of the interventions.