Suicide. It’s not something we like to talk about—especially when we’re talking about our kids. Yet it’s a painful reality in our world today. Unfortunately, most of us know someone in our community whose child has died by suicide.

There’s good news and bad news on teen suicide rates.

Let’s have the good news first. According to one recent study by Substance Use and Mental Health Services Administration, rates of suicidal ideation among teens—thinking about suicide—dropped modestly from 12.9% in 2021 to 10.1% in 2024, and documented suicide attempts dropped from 3.6% in 2021 to 2.7% in 2024.

Advertisement

X

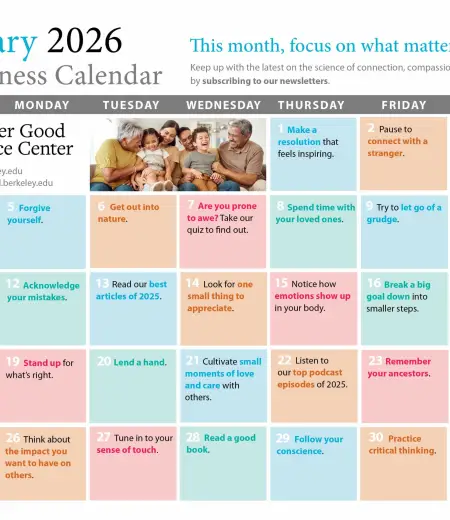

Keep Up with the GGSC Happiness Calendar

Focus on what matters to you this month

Now the bad news. This means that one in 10 teens aged 12 to 17, or 2.6 million teens, thought seriously about ending their life in 2024, and an additional 13.5% were unsure or didn’t want to report whether they were having thoughts of suicide, indicating that these estimates are likely much higher. In addition, teens who identify as LGBQ+ fare much worse; 41% of students identifying as LGBQ+, compared to 13% of those identifying as heterosexuals, seriously considered suicide.

Clearly, there’s much work still to be done to address the unacceptable reality that our youth are deeply in pain. So how does a teen find their way through? According to new research I conducted with colleagues, practicing self-compassion could be a promising source of strength and support.

Feeling less alone

Funded by the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, my colleagues and I recently enrolled transgender teens who experienced suicidal ideation in an eight-session self-compassion course, called Mindful Self-Compassion for Teens (MSC-T). Teens learned tools for supporting and being kind to themselves when facing situations that were emotionally hard.

Importantly, the participants learned that they weren’t alone in what they were feeling—that experiencing sadness, loneliness, and anxiety, for example, was a normal part of being human. Certainly, the situations that prompt those feelings differ across teens, but, nonetheless, the teens came to understand that all humans experience feeling alone, sad, angry, and hurt. Most of all, they learned that there was something they could do—exercises and practices they could engage in—to support themselves when they felt this way.

For example, in one session of MSC-T, teens participated in an exercise called “How Would I Treat a Friend” that helped them realize that they were much kinder and more supportive to their friends than they were toward themselves when struggling with something difficult. This led them to recognize moments when they felt stressed or “less than,” ask themselves how they would treat a friend in this situation, and treat themselves in a similar way. They then learned specific tools to do this—to support themselves—such as using a comforting physical gesture like putting their hand on their heart, or grounding themselves by noticing the sensations of their feet on the floor.

Through learning these practices across the study, teens decreased in suicidal ideation from before to after taking MSC-T, and their thoughts about suicide continued to decrease over the next two months. Teens with greater increases in self-compassion experienced greater decreases in suicidal ideation.

Teen participants had the opportunity to share their thoughts about how the program unfolded for them. Our analyses yielded three themes: They felt accepted and safe within a supportive community, experienced self-growth, and experienced a sense of mattering.

First, many expressed that being with others with a similar identity in a safe space allowed them to feel a sense of connection and that they “belonged,” something that they often didn’t experience in other contexts. As one teen shared, “It was really wonderful to get to talk about our experiences without having to explain things again and again and have other people just understand and accept you and your experiences completely.” Here, the teen articulates a basic human need: to be seen, accepted for who you are, and integrally connected in a community.

The second theme described the self-growth that teens experienced through taking the class. Many voiced an appreciation for the coping and self-regulation skills that they gained. They shared that they valued the “toolkit” of skills that they now had in their back pocket to retrieve when feeling overwhelmed with emotion. One teen commented on the usefulness of grounding techniques when anxiety and depression were high, and another commented on the calming effect of the techniques and how these techniques helped them care for themselves.

Finally, the third theme reflected the sense of mattering—the teens wanted to be seen, heard, and understood as the complex and multifaceted individuals that they were. One commented that they appreciated that the facilitators were “open to feedback” and another valued the fact that “you didn’t have to do anything that didn’t work for you.” For some, contributing to the curriculum content was important. Mostly, having their voices heard and valued was critical.

Bringing self-compassion to teens

Previously, the teen years were thought of as a time of “storm and stress” and a stage where you simply hold tight until you make it through. Thinking about the teen years in this way is no longer considered accurate by adolescent researchers and psychologists.

In fact, the psychologist Daniel Siegel talks about these years as being a time of opportunity, growth, and exploration—a time to discover one’s own purpose and agency. Undeniably, it’s a time when a lot is changing and teens often find themselves on unsteady ground, but it doesn’t have to be a rabbit hole of despair.

Youth thinking about suicide does not have to be pervasive in our society. Self-compassion offers teens a way to understand their emotional pain and, more importantly, manage this pain and grow from it. A 2024 study found that when college students met the stressful experiences in their lives with self-compassion, they became more resilient over time.

Teens need self-compassion skills so that they, too, can become more resilient. If you want to incorporate self-compassion lessons into your school, I recently published a book detailing a 16-session in-school self-compassion curriculum for teens, including 15-minute “drop-in” sessions that school counselors can deliver in the classroom. We also launched a new website filled with self-compassion resources specifically for teens. Books and other resources are also available.

At the end of 2021, then–U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy warned us of the youth mental health epidemic in his Youth Mental Health advisory: “The challenges today’s generation of young people face are unprecedented and uniquely hard to navigate. And the effect these challenges have had on their mental health is devastating.”

We have the tools and the knowledge to help our youth navigate these challenges, including suicidal ideation. Now let’s work together to do everything we can to arm our children with what they need to contend with 21st-century society.