City plans not only involve specific regions and income classes but also substantive themes. Thus, each city plan was analyzed based on (1) dimensions of health, (2) equity and (3) implementation readiness.

Dimensions of health

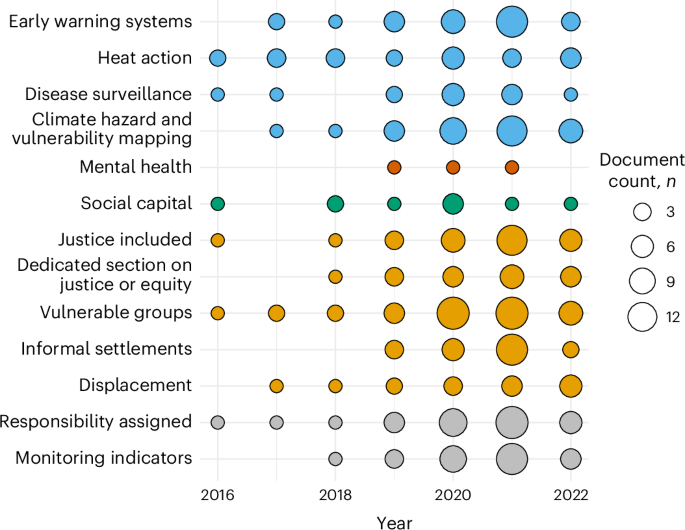

Health was divided into six themes across physical, mental and social health. Figure 3 shows the document themes by year of plan approval, with the subsequent subsections providing more detailed findings per theme. The larger circles over time are representative of more overall documents and not increased proportion of theme prevalence.

Fig. 3: Prevalence of health prioritization levels across core climate adaptation themes.

Each color represents a thematic group. The blue dots show the physical health themes; dark orange, mental health; green, social capital; orange, justice and equity themes and gray, implementation readiness themes.

Physical health

Here we define physical health indicators as health adaptation that addresses physical health concerns at a systems level—commonly referred to as direct health impacts from climate change. This includes disease burden and risk of injury or death from climate hazards. We coded physical health based on the indicators used in ref. 22. Their health indicators were chosen from commonly referenced climate–health actions in the literature, covering topics of emergency response, mapping, preparedness and heat action22. We were specifically interested in adaptation strategies that were human-focused. Adaptation strategies that were focused on built infrastructure without connection to human health were not considered.

Overall, physical health is the most common form of health integration. Out of the plans that included health adaptation strategies (Extended Data Table 1), all but one included at least one physical health component. Hazard and vulnerability mapping was the most integrated, with 56% of plans integrating a hazard and vulnerability assessment into their plan or stating an intention to do so. Also, 51% of plans included early warning systems, out of which 22 were for hazards (floods, droughts and stormwater), 10 were for extreme heat and 2 were focused on disease. Furthermore, 40% of plans included heat actions. This included blue and green infrastructure, operating cooling shelters, awareness and education activities, heat vulnerability mapping, alert and early warning systems, capacity and training at healthcare facilities, altering occupational health standards to reduce exposure, and developing or updating heat action plans. Fourteen plans (25%) included disease surveillance measures.

Some plans included additional adaptation strategies outside of the four categories above. Strategies on climate-resilient health systems included capacity building, training for health staff and first responders, improving access to care and increasing public awareness, climate and health research and plan development, vector control and strengthening of health systems. Two plans included strategies to reduce illness from contaminated food and food procurement, whereas nutrition and food systems were more common. One plan mentioned sustainability of health systems and reducing waste and emissions of health facilities and one plan mentioned implementing a one-health approach. Although strengthening health systems can lead to mental and social co-benefits, this was only coded as a physical health strategy unless mental health was directly mentioned. The core focus of health system strategies was on healthcare delivery and disease.

There were several health-adjacent topics that were commonly covered in plans from an infrastructure or mitigation perspective. These included air pollution, water and sanitation, urban heat islands, and nutrition and food systems. Health was secondary or not included in the content of these sections, and therefore, they were not included in our code strategy as a health adaptation measure. For example, water and waste was discussed as an infrastructure issue in mitigation sections in which health was a co-benefit. It is still important to acknowledge that strategies in these sectors exist, and there is an opportunity to optimize the health benefits and components of these strategies.

Other studies have also found a dominance of physical health in health adaptation literature27. So far, physical health is the common understanding of health impacts and health adaptation, and therefore, it is expected that most—if not all—of health integration would focus on physical health components. The emphasis on flooding and heat is similar to other studies13,21,23.

It is important to note that not all of the strategies included here are a direct health adaptation strategy. For example, hazard early warning systems can be designed and implemented with little regard for health even if they have a health benefit when enacted. Similarly, not all heat action is done through a health framing. As such, it is important to consider the vast array of health topics that are still missing from adaptation discussions at a city level. Future studies can consider a more stringent coding system for climate-resilient and sustainable health systems18, as well as other adaptation strategies that directly address disease, injury and mortality23.

Mental health

Previous analyses of city climate plans have had limited inclusion of mental health. We only located one study that reviewed global city adaptation plans and included mental health23. As such, we wanted to determine if mental health is included in city adaptation planning, and if so, how it is integrated (Extended Data Table 2). We found that mental health was rarely considered. Houston was the only city to have a dedicated section on mental health, with one of their three mental health strategies specific to climate adaptation. Houston acknowledged the mental toll that previous disasters have had on residents even years later: “Hurricane Harvey Registry found that two-thirds of the respondents reported intrusive or unintended thoughts about Harvey and associated flooding. This trauma is not only from one hurricane, but from repetitive flooding in some neighborhoods as well as daily fears of violence, poverty, isolation and loneliness that many Houstonians experience on a regular basis.”

The city’s mental health strategy aims to train first responders in psychological first aid to increase the support provided in the aftermath of a disaster. The city included two other mental health interventions not specific to climate change to provide peer-to-peer and professional mental health support to youth. Houston’s plan may have been more likely to include mental health as their plan was a city resilience plan, which was not exclusive to climate change. In general, we found resilience plans or climate action plans with a non-traditional format were more likely to include mental health, social health or equity. Further, the city of Houston has had numerous large-scale disasters (Hurricane Harvey, Tropical Storm Imelda) in recent years, which could have influenced inclusion.

Cape Town included an adaptation strategy on mental health with the broad intention to include mental health in their climate response and to integrate intersections between mental health strategies in the city’s resilience plan with their climate actions. Chicago’s plan, like Houston’s, was a city resilience plan, included mental health strategies outside of climate adaptation. These included training for emergency personal to improve crisis response for individuals with mental illness.

A handful of plans included the words “mental health” either acknowledging there can be mental health impacts to climate change or that there are mental health and well-being co-benefits to some adaptation strategies—blue and green infrastructure, for instance. These occurrences show that there is some awareness of mental health outcomes to climate mitigation and adaptation strategies (both beneficial and maladaptive) at the city level, although significantly less than physical health awareness. There is more ground to gain to achieve comprehensive and direct adaptation strategies targeting mental health.

Very little mental health presence aligns with similar studies. In the typology of urban health adaptation in ref. 23, the authors reviewed 369 actions across 98 cities and found no mental health adaptation strategies. Most research on climate and mental health at the city level focuses on heat as the main exposure28,29, with most research on climate and mental health, irrespective of geography, centering on quantifying impacts or co-benefits28,30. Previous studies have called for increased focus on mental health in climate health and vulnerability and adaptation assessments27. Although these assessments can be completed at any level of jurisdiction (municipal, regional and national), majority are completed at a country level31. Further, research shows that mental health integration is doing little better at a national level with only 8 out of 38 Nationally Determined Contributions referencing mental health19,32,33. WHO recently found similar mental health inclusion in NAPs, with 5% including mental health adaptation strategies26. HNAPs performed better still, with 22% including adaptation strategies for mental health26. Our findings further confirm gaps on mental health that are prevalent throughout the climate policy landscape and highlights the opportunity for subnational leadership in this area.

Social capital

Social health refers to interpersonal relationships such as the quality of social interactions and community integration, which are considered an essential element of good health and well-being34. Here we focus on social capital as the social health proxy for adaptation strategies that enhance community resilience and build social support. Ten plans included elements of social capital. These include social support mechanisms like building resilience hubs and integrating social support into emergency response including elderly support networks and establishing neighborhood emergency plans (Extended Data Table 3). Other strategies focused on overall community cohesion and varied from better understanding social capital to investing in sports, culture, art and education. We did not code specifically by subpopulation (women, children, elderly). However, when subgroups were mentioned, the elderly were most commonly targeted by social cohesion measures. One plan, Rio, specified actions for children including access to education, sports and culture.

Terms related to social capital (community, social cohesion and inclusivity) were most used to refer to public participation and curating both community and community organization involvement in the climate planning progress or for transferring responsibility for adaptation strategies onto community and individual behavior. Although it is important to have public participation in planning processes and having strong public involvement can lead to a stronger focus on equity35,36, it is not directly relevant to social cohesion as defined here. As such, when these terms were used in this way, it was not coded as being relevant to social health.

Some plans integrated elements of social determinants of health outside of social cohesion. In particular, plans that had a strong equity focus or followed a non-traditional structure (such as Rio or Barcelona) had more strategies addressing social issues. The most common involved providing access to safe, affordable and climate-resilient housing and providing increased access to economic opportunity. There are strong overlaps between social health, equity and vulnerability, particularly with regard to climate resilience. Both housing and income are essential for good health and well-being37,38 and for resilience to climate impacts2,39, yet these are not considered standard in climate action planning. Further, community cohesion has been found to improve outcomes after disasters40 and on the opposite end, social isolation is tied to worse health outcomes41.

Some studies have looked at the role of social capital in urban case studies. Guardaro et al.42 explored social capital and urban heat risk. Opoku-Boateng et al.43 and Shahid et al.44 examined the role of social capital in informal settlements in Ghana and Pakistan, respectively. All three noted that social capital is an underutilized resource in climate resilience, although there was notable variation in how social capital was defined42,43,44. Examining the social determinants of health in urban centers is not new45; however, there has been less integration on their relevance in climate policy. Friel et al.45 argued for joint action on climate mitigation and adaptation and addressing social determinants of health, whereas others have called the climate crises a determinant of health in its own right46. More studies can look at the inclusion of social capital, social cohesion and social resilience as a consideration of social health in climate adaptation. To the best of our knowledge, this has not yet been explored in the literature.

Equity and vulnerability

Unlike health, justice, equity and vulnerability content was coded outside of adaptation strategies. We determined if there was a justice or equity focus across two areas: presence of justice or equity and vulnerable groups (Extended Data Table 4). Presence of justice and equity was determined if the words justice and equity were used and if there was a dedicated section on justice, equity or vulnerability. We did not further code by type of justice as this has been looked at by other studies35. Plans were considered to have discussed vulnerable groups if there was dedicated text on population groups that were at a differentiated risk than the general population. We further looked at two specific elements that enhance vulnerability, namely, displacement and informal settlements.

We found that almost half (49%) of the plans sufficiently included justice, with 33% having a dedicated section and 65% using the words justice or equity. Plans that only vaguely mentioned that climate change has inequitable impacts but did not integrate justice into their approach were not classed as having sufficiently included justice but were coded as having used the words justice or equity when applicable. Also, 75% of plans mentioned vulnerable populations, with varying levels of inclusion. This could be one or two sentences up to a dedicated section on vulnerability and specific adaptation strategies. Furthermore, 40% of plans mentioned informal settlements and 29% mentioned climate displacement.

Overall, justice and equity content were most discussed in the background sections. Some plans grounded their whole approach from a justice framework by incorporating it in the plan’s goal. However, similar to health, there was often limited follow-through on integrating justice into the adaptation strategies. Three plans also used a strong gender lens in addition to an equity lens. The word “inclusion” was commonly used to denote themes of justice or equity, with some plans even using inclusion as a third pillar of the plan after mitigation and adaptation.

When looking at content related to displacement, climate displacement was most commonly mentioned in relation to climate hazards or sea-level rise that could lead to displacement of populations within the city, often from informal settlements. Only two plans acknowledged receiving displaced communities from elsewhere and included preparing for climate refugees into an action item.

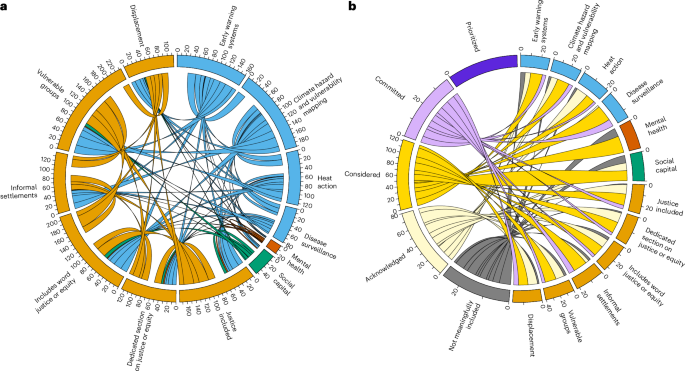

We wanted to extract the relationship between health and equity in C40 adaptation planning. Figure 4a shows a co-occurrence chord diagram highlighting which plans had health and equity themes co-occurring within each plan. The figure shows unidirectional relationships from the starting theme (base color) to the end point. For example, social cohesion (green) shows that plans that had social cohesion strategies also had a section on justice or equity and discussion on vulnerable groups including mention of climate displacement.

Fig. 4: Visualizing the co-occurrence of themes in C40 adaptation plans alongside equity (a) and health prioritization level (b.)

a,b, Co-occurrence of coded themes (a) and coded themes with health prioritization level (b). The outside bands show the total count of co-occurrences that the theme had across all themes. For example, early warning systems co-occurred 161 times with the themes, whereas the bands show which terms early warning systems co-occurred with. They are color coded by the thematic group. Panel b shows the co-occurrence of health prioritization level across each theme.

The bands on the outside show the base color of each theme and the proportionality of that theme in our overall sample. First, looking at the outside bands, most health codes fall into either early warning systems, hazard and vulnerability mapping, or heat action. These are health-adjacent codes as all of them can be done without a health focus. Strategies that directly target a health concern (disease, mental health or social cohesion) were less common, with mental health being the least common of the three. Similarly, on the justice side (orange), the umbrella categories—vulnerable groups and overall justice inclusion—were more prevalent in the plans than specific terms such as informal settlements or climate displacement. This is expected as not all cities included here have populations living in informal settlements.

Interestingly, mental health and social cohesion rarely co-occurred with physical health indicators but did co-occur with justice. This shows that mental and social health strategies were incorporated more from an equity perspective than a health one. This is further supported compared with health prioritization categories in which mental health and social health were more common in plans that had a lower health prioritization category than the physical health indicators (Fig. 4b, purple).

Implementation readiness

We incorporated two proxy variables to gauge implementation readiness. We assessed implementability through responsibility designation and the presence of monitoring indicators. Majority of plans (62%) designated a city department that was responsible for each adaptation strategy, with some plans designating a lead agency and supporting agencies. Also, 51% of plans included indicators. However, indicators were sometimes distantly related to the adaptation strategy.

The distinction between awareness and action could be tied to time and ambition. Many of the current health adaptation strategies reflect early stages of the policy process (such as planning). This includes intention to develop future plans or to complete additional research or mapping. Funding and capacity are often cited as limiting factors to implementation and could lead to lower levels of ambition on health adaptation13.

Further, many of the strategies listed were not granular enough for implementation. For example, many of the disease surveillance measures lacked specificity (for example, “strengthen effective climate-sensitive disease surveillance and prevention programmes”). It remains unclear how these initiatives will be implemented, what diseases will be targeted and if any implementation has occurred. Vague or broad climate adaptation strategies show a limit to operationalization. However, it is possible that these strategies would be followed up in other plans and strategies with more detail.

Moreover, the segmentation of sectors leads to challenges on planning and implementation. This was evident in the varied location of health strategies in climate plans. Plans that did not have a health section had health adaptation strategies integrated across other headings either under adaptation broadly, under social impacts, disaster management, or under vulnerability or equity subheaders. Last, the early establishment of health as a co-benefit could lead to challenges reframing and reintegrating health as a primary adaptation element.

Limitations

Our methodology does pose several limitations. First, the screening favored English-language documents. In cases where an English version was accessible online, this version was included. However, the English translation was sometimes shorter in length (that is, a summary version) or was written in simpler vernacular. If an English version was not located, Google Lens was used to translate and review the documents in English. In both cases, it is possible there is content in the original plan that was not represented in the English version or that there were errors in the translations provided.

Further, we only used one plan per city based on what was reported by cities into the CDP database. We determined that this was the most uniform method of analysis between cities, aligning with both C40’s published plans47 and similar studies22,35. Including additional documents from a manual search of city websites would have led to high levels of variation in information on each city and being unable to confirm the totality of the information gathered. It is possible that there are more recent plans (since August 2023) or other city planning documents that integrate elements of health adaptation, which are not included in this analysis. As CDP is self-reported, the cities are choosing the documents they determine are the most representative of their city’s climate adaptation planning. There are limits to the CDP database itself. In particular, it is self-reported, which could lead to inaccuracies in the data. As all plans were reviewed manually, there was little reliance on CDP reported statistics beyond the initial sample selection.