Shutterstock/Xharites

Shutterstock/Xharites

Burnout rates among paramedics and first responders reached 56% globally after COVID-19, with many providers not seeking help.Structured mental health counseling reduced burnout and suicidality in EMS providers when it was accessible, trusted, and proactive.Barriers to mental health care included stigma, confidentiality concerns, and cost, which hindered access to effective support for EMS personnel.

By William Rivera III, DHSc, NRP

The Breaking Point

When the first calls during COVID-19 began, paramedics and first responders had no idea how much their world and environment were about to change. Initially, there were just whispers of a new virus, then a few suspected cases materialized. Within a short time, ambulance crews were dispatched from one critically ill patient to the next, personal pro

tective equipment (PPE) supplies ran critically low and EMS crews found themselves in unknown anticipation during one of the most chaotic medical crises in recent history.

EMS providers and first responders continued to do their jobs, but the emotional fallout was overwhelming. Prior to the pandemic, prehospital care was already a career with higher burnout and suicidality than the general population.

The pandemic added fuel to the fire. Call volumes skyrocketed, paramedics and first responders consistently worried about infecting their families and loved ones, and physical and emotional fatigue gave way to hopelessness.

Research confirmed what most EMS veterans already understood as the toll was unparalleled. Burnout rates after COVID-19 reached 56% globally.1 The harsh reality was that many of the paramedics and first responders who needed help never asked for it.

The “Suck It Up” Culture

EMS culture had long been immersed in toughness. From the beginning, new EMS providers were trained to manage chaos, persevere through exhaustion and keep their emotions in check.

That mindset was vital in life-and-death scenarios, but when it became the primary way to process trauma and loss, the lasting results were devastating.

The stigma remained influential and present in many organizations. Numerous paramedics and first responders feared that acknowledging mental health struggles would mark them as weak, damage their careers or isolate them from their peers.2

As one participant in the study bluntly stated, “You don’t want to be the medic everyone whispers about.” The mentality to stay strong may have allowed providers to be efficient on the scene, but off scene it tore down their resilience, promoted burnout and fueled suicidality.

Why Mental Health Matters in EMS

The literature revealed that paramedics and first responders were among the most at-risk groups for cumulative stress, depression, burnout, and suicidality due to consistent exposure to trauma and long, unpredictable work schedules.3,4

In North Carolina alone, surveys recognized burnout in more than 60% of EMS providers. Studies validated that without structured mental health support, consequences included medication errors, compassion fatigue, reduced patient satisfaction and higher provider turnover.5

Asking Hard Questions

To move past assumptions, I conducted an applied research study during the pandemic with more than 370 paramedics and first responders across North Carolina.

This mixed-methods project combined quantitative surveys, qualitative interviews and standardized psychological assessments, using grounded theory and phenomenology to capture both empirical patterns and lived experiences.6,7

The central question was clear: Did counseling reduce suicidality and burnout in EMS providers? The findings indicated that it did, but only when counseling was accessible, trusted, and proactive.

This study built upon a comprehensive literature review that detailed how paramedics and first responders faced increased rates of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), burnout, and suicidality during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Research consistently demonstrated that although mental health interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), critical incident stress management (CISM) and employee assistance programs (EAPs) offered promise, organizational obstacles such as stigma, limited access to proper care, and confidentiality concerns reduced their effectiveness.2,8

Grounded theory and phenomenology provided guiding frameworks to portray both the measurable impacts and the lived experiences of paramedics and first responders, recognizing that resilience was not only shaped by data, but also by personal meaning.

The methodology incorporated quantitative surveys, qualitative interviews, and psychological assessments to create a mixed-methods approach that emphasized both patterns and narratives. With more than 370 participants, the study established a comprehensive picture of the mental health needs of EMS providers.

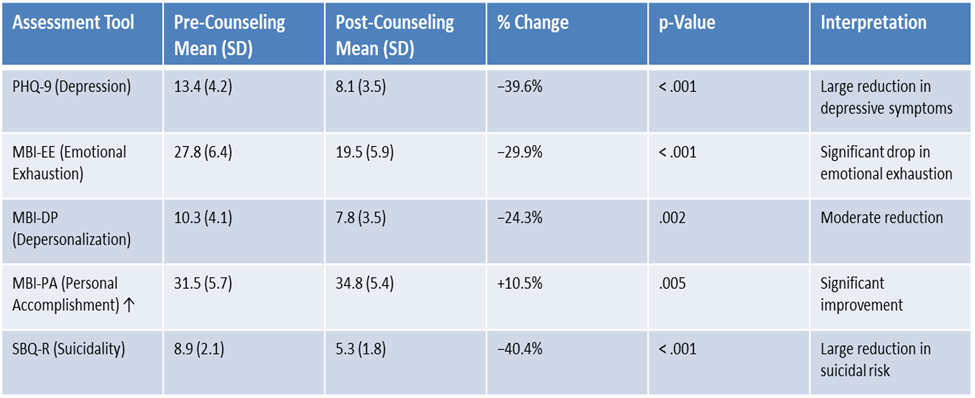

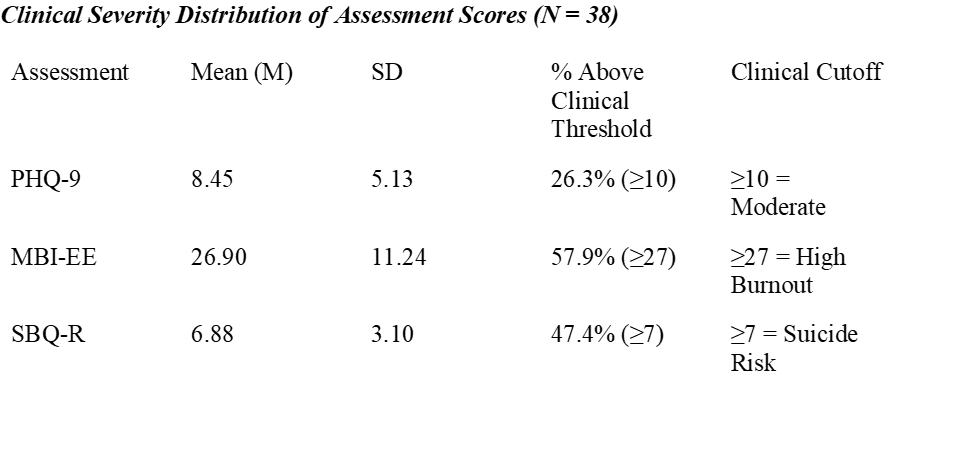

Surveys revealed elevated burnout and suicidality, while interviews uncovered themes of stigma, mistrust of organizational programs, and unmet demand for trauma-informed counseling. Psychological assessments statistically confirmed significant reductions in suicidality and burnout among those who participated in structured mental health counseling.

The results highlighted a clear message: proactive, trauma-informed, and structured counseling works. Counseling not only minimized negative EMS mental health outcomes, but it also improved resilience, job satisfaction, and provider retention.

However, inadequacies remain in availability, affordability and organizational trust. The study’s evidence demonstrated that EMS organizations need to address clinical and systemic stressors if they want to establish and maintain a sustainable workforce.

Without proactive and targeted interventions, burnout and suicidality continue to threaten the stability of EMS systems nationwide.

What We Learned: Counseling Worked

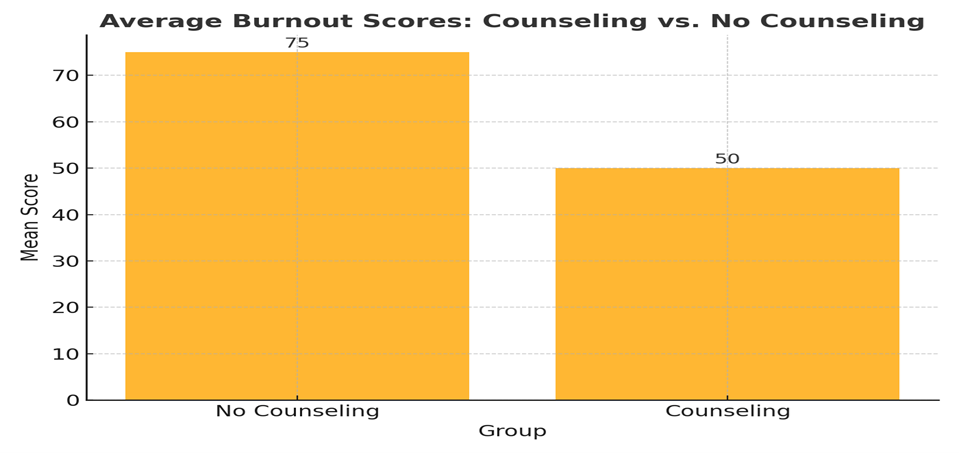

Participants involved in structured counseling scored substantially lower on burnout and suicidality assessments.

They expressed enhanced coping mechanisms, improved resilience, and renewed job satisfaction. These results supported evidence illustrating the effectiveness of CBT,9 CISM,10 and resilience training.11

Figure 1. Average burnout scores among participants with and without counseling.

Figure 1. Average burnout scores among participants with and without counseling.

Figure 2. Average Scores. Pre- and post-counseling.

Figure 2. Average Scores. Pre- and post-counseling.

Figure 3. Clinical severity distribution of assessment scores.

Figure 3. Clinical severity distribution of assessment scores.

Barriers Persisted

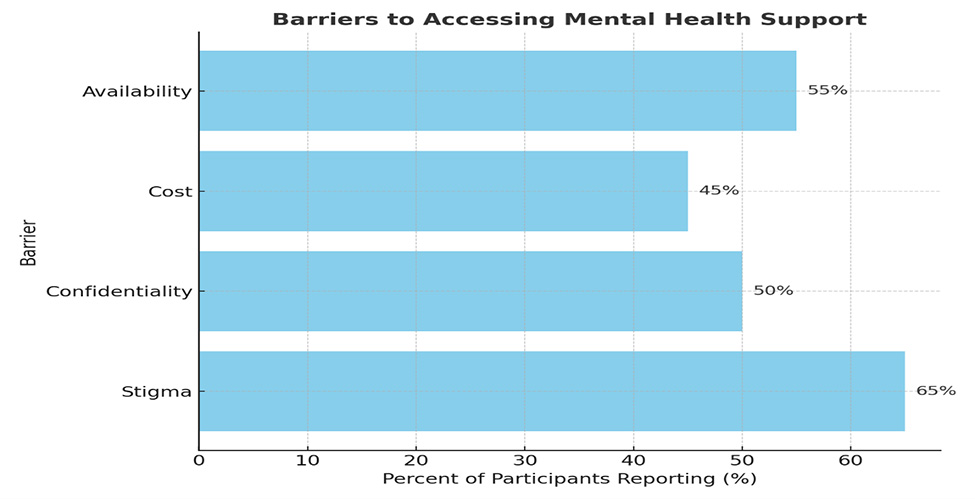

Unfortunately, effectiveness did not equate to access. Participants consistently reported several barriers to mental health care such as stigma, confidentiality concerns, and cost, and long wait times to see a knowledgeable provider.

They often feared judgment and/or career damage and they worried that employer-provided interventions were not completely private. Experiencing gaps in insurance coverage, some reported that they were forced to pay out-of-pocket.

Others stated that long wait times to see a provider led them to simply giving up.

Figure 4. Reported barriers to accessing mental health counseling among EMS participants.

Figure 4. Reported barriers to accessing mental health counseling among EMS participants.

Peer Support Was Valuable But Flawed

Many agencies primarily leaned on peer support. Although some medics found it helpful, others questioned whether their peers were adequately trained, and most importantly, trustworthy.

Without proper preparation and structure, peer support teams risk being seen as nothing more than “lip service” rather than real help.12 Efficient peer support needed to be structured, organized, trained, trusted, and continuously evaluated.

Faith-Based Counseling Offered Relief

Several participants felt that chaplains and faith-based counseling had provided substantial support.

For them, resilience was both spiritual and psychological. Integrating faith into counseling created the difference between merely tolerating the job and finding restored purpose in it.

Telehealth Opened Doors

A positive outcome of the pandemic was the increased use of telehealth appointments. For medics who had been hesitant about in-person visits or who lived in rural areas, virtual counseling sessions became a safe and convenient refuge. Telehealth mitigated barriers of time, travel, and stigma.13

For some, participating in a confidential session from their home felt more secure than walking into a clinic. The findings suggest that telehealth needs to remain a foundation of EMS mental health strategies moving forward.

Tools That Worked

Evidence showed that certain counseling modalities were particularly effective for EMS providers: cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) and resilience training.

CBT helps reframe negative thought patterns and develop healthier coping mechanisms;8 EMDR helps process trauma and reduces the intensity of disturbing memories; and specifically designed resilience training programs teach stress management, self-care and peer connection to build long-term perseverance.

EMS agencies that incorporated these approaches into organizational wellness programs observed stronger, happier, and more resilient medics.

Recommendations for EMS Leaders

The results of this study pointed directly to actions EMS agencies must adopt.

Normalize Counseling

Since structured counseling measurably reduced burnout and suicidality, agencies should implement routine mental health screenings and annual counseling as preventive care—not corrective action.

Participants who received counseling improved significantly, but many still struggled to access services. Agencies must partner with trauma-informed providers, expand telehealth, and ensure services are free or affordable.

The study showed peer support was underutilized due to mistrust. Agencies must vet, train and continually evaluate peer support programs to ensure confidentiality and competence.

Address Systemic Stressors

Data demonstrated that counseling improved outcomes, but interviews made it clear that organizational issues—like mandatory overtime and understaffing—continued to drive burnout. Counseling must be paired with systemic reforms.

Many participants credited faith-based and family-centered counseling as crucial. Agencies must recognize that resilience is multifaceted and they should provide diverse support options.

Changing the Culture

Real and effective change necessitates a cultural shift. Leaders must encourage vulnerability, standardize conversations about mental health and change punitive attitudes toward help-seeking.

Imagine a workplace where saying “I have an appointment with my counselor” is as normalized as stating “I have a dental cleaning.” The EMS profession has always been proud of its resilience. True resilience is not suffering in silence.

Instead, it is understanding when to ask for support and having the courage to accept it.

The Path Forward

The pandemic revealed critical failings in EMS mental health support that can no longer be brushed aside. Counseling works and it saves lives.

Until stigma is removed and access is improved, many providers will continue to fall through the cracks. EMS leaders have a simple choice: maintain the traditional “suck it up” mentality or build a new culture in which medics are supported as whole human beings.

The future of the EMS workforce depends on it. It’s time to remove silence and replace it with support. In EMS, taking care of each other is just as important as taking care of our patients.

More from JEMS

Bonnie Rumilly’s Journey Through Trauma and Resilience

EMS Frontline Fatigue in Focus: A Profile of Intervention Strategies Driving Change

Our Approach to Mental Health Is Not Working

The Truth You Don’t Want: An EMS Veteran on PTSD, Stigma and the Fight to Stay Whole

About the Author

William Rivera III, DHSc, NRP is a paramedic with Cape Fear Valley EMS and a doctoral student in Health Sciences at Liberty University. He previously served as a Weapons Squad Leader in the U.S. Army and a Squad Leader in the U.S. Marine Corps. With a background in senior fitness management and personal training, he focuses his research on reducing PTSD, burnout and suicidality among first responders.

References

1. Reardon, M., Abrahams, R., Thyer, L., & Simpson, P. (2020). Review article: Prevalence of burnout in paramedics: A systematic review of prevalence studies. Emergency Medicine Australasia, 32(2), 182–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/1742-6723.13478

2. Hazell, C. M., Fielding-Smith, S., Koc, Y., & Hayward, M. (2022). Pilot evaluation of a brief training video aimed at reducing mental health stigma amongst emergency first responders (the ENHANcE II study). Journal of Mental Health, 33(5), 587–595. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2022.2069707

3. Canu, I. G., Marca, S. C., Dell’Oro, F., Balázs, Á., Bergamaschi, E., Besse, C., Bianchi, R., Bislimovska, J., Bjelajac, A. K., Bugge, M., Busneag, C. I., Çağlayan, Ç., Cernițanu, M., Pereira, C. C., Hafner, N. D., Droz, N., Eglite, M., Godderis, L., Gündel, H., . . . Wahlen,

A. (2020). Harmonized definition of occupational burnout: A systematic review, semantic analysis, and Delphi consensus in 29 countries. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 47(2), 95–107. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3935

4. Kaplan, G. R., Frith, T., & Hubble, M. W. (2023). Quantifying the prevalence and predictors of burnout in emergency medical services personnel. Irish Journal of Medical Science, 193(3). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-023-03580-7

5. Jeanmonod, D., Irick, J., Munday, A., Awosika, A., & Jeanmonod, R. (2024). Compassion fatigue in Emergency Medicine: Current perspectives. Open Access Emergency Medicine, Volume 16, 167–181. https://doi.org/10.2147/oaem.s418935

6. Akkaya, B. (2023). Grounded theory approaches: A comprehensive examination of systematic design data coding. International Journal of Contemporary Educational Research, 10(1), 89–103. https://doi.org/10.33200/ijcer.1188910

7. Gallagher, S. (2022). What is phenomenology? In Phenomenology. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-11586-8_1

8. Bergen-Cico, D., Kilaru, P., Rizzo, R., & Buore, P. (2020). Stress and well-being of first responders. Handbook of research on stress and well-being in the public sector. Edward Elgar Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788970358.00013

9. Bryant, R. A., Kenny, L., Rawson, N., Cahill, C., Joscelyne, A., Garber, B., Tockar, J., Tran, J., & Dawson, K. (2021). Two‐year follow‐up of trauma‐focused cognitive behavior therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in emergency service personnel: A randomized clinical trial. Depression and Anxiety, 38(11), 1131–1137. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.23214

10. Price, J., Landry, C. A., Sych, J., McNeill, M., Stelnicki, A. M., Asmundson, A. J. N., & Carleton, R. N. (2022). Assessing the perceptions and impact of critical incident stress management peer support among firefighters and paramedics in Canada. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), Article 4976. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19094976

11. Beauchamp, A., Ponder, W., & Jetelina, K. (2023). Dissecting the interrelations of suicidality and mental health across first responder subtypes seeking treatment: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Social, Behavioral and Health Sciences, 17(1).

https://doi.org/10.5590/jsbhs.2023.17.1.04

12. Auth, N. M., Booker, M. J., Wild, J., & Riley, R. (2022). Mental health and help seeking among trauma-exposed emergency service staff: A qualitative evidence synthesis. BMJ Open, 12(2), Article e047814. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-047814

13. Haimi, M. (2023). The tragic paradoxical effect of telemedicine on healthcare disparities- a time for redemption: A narrative review. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making, 23(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-023-02194-4