Editor’s Note: This story discusses suicide and mental illness. Reader discretion is advised.

Margaret “Maggie” Murphy said she lives a wonderful life. She was a good student growing up and considered herself a nerd as a child.

Murphy said she’s lucky to have the life she does. But anxiety and depression have challenged her throughout it. There have been times when she struggled to get out of bed. Sometimes, she said, she couldn’t get out at all.

“There’s some things I need to talk through with a counselor or a therapist,” Murphy said. “There’s sometimes when a medication that I take happens to be Prozac, and if for any reason, I do not take that, I will become very depressed.”

She spent adulthood working as an administrator in end-of-life care for 20 years in Massachusetts for a nonprofit. In 2016, she returned to the Lehigh Valley for a career switch.

Murphy now works as the executive director of the Lehigh Valley Chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness. The non-profit organization was founded in 1979 around a kitchen table in Wisconsin, when families affected by mental illness realized they weren’t alone. According to the organization’s website, it has evolved into the nation’s largest grassroots mental health organization.

As the executive director, Murphy said she empathizes with everyone she helps and wants people to know her story.

An estimated one in five adults in the U.S. live with a mental illness, according to the National Institute of Mental Health. The American Association of Suicidology reported 49,316 suicide deaths in 2023.

Suicide is the 11th leading cause of death in the U.S., and those numbers have remained largely stagnant.

In 2018, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported an age-adjusted suicide rate of 14.2 deaths per 100,000 people. Although the rate decreased from 2019 to 2021, it rose again to 14.2 in 2022.

Murphy and members of other nonprofit organizations across the Lehigh Valley are working to change those statistics.

The Lehigh Valley chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness and Pinebrook Family Answers aim to connect people with support early — before a mental health crisis or before someone considers suicide.

In the Lehigh Valley, this nationwide issue is prevalent. The Lehigh County Coroner’s Office and Forensic Centers reported 60 suicide deaths between January and November 2025.

Lehigh County Coroner Daniel Buglio said he anticipates the total will exceed last year’s count of 64 deaths.

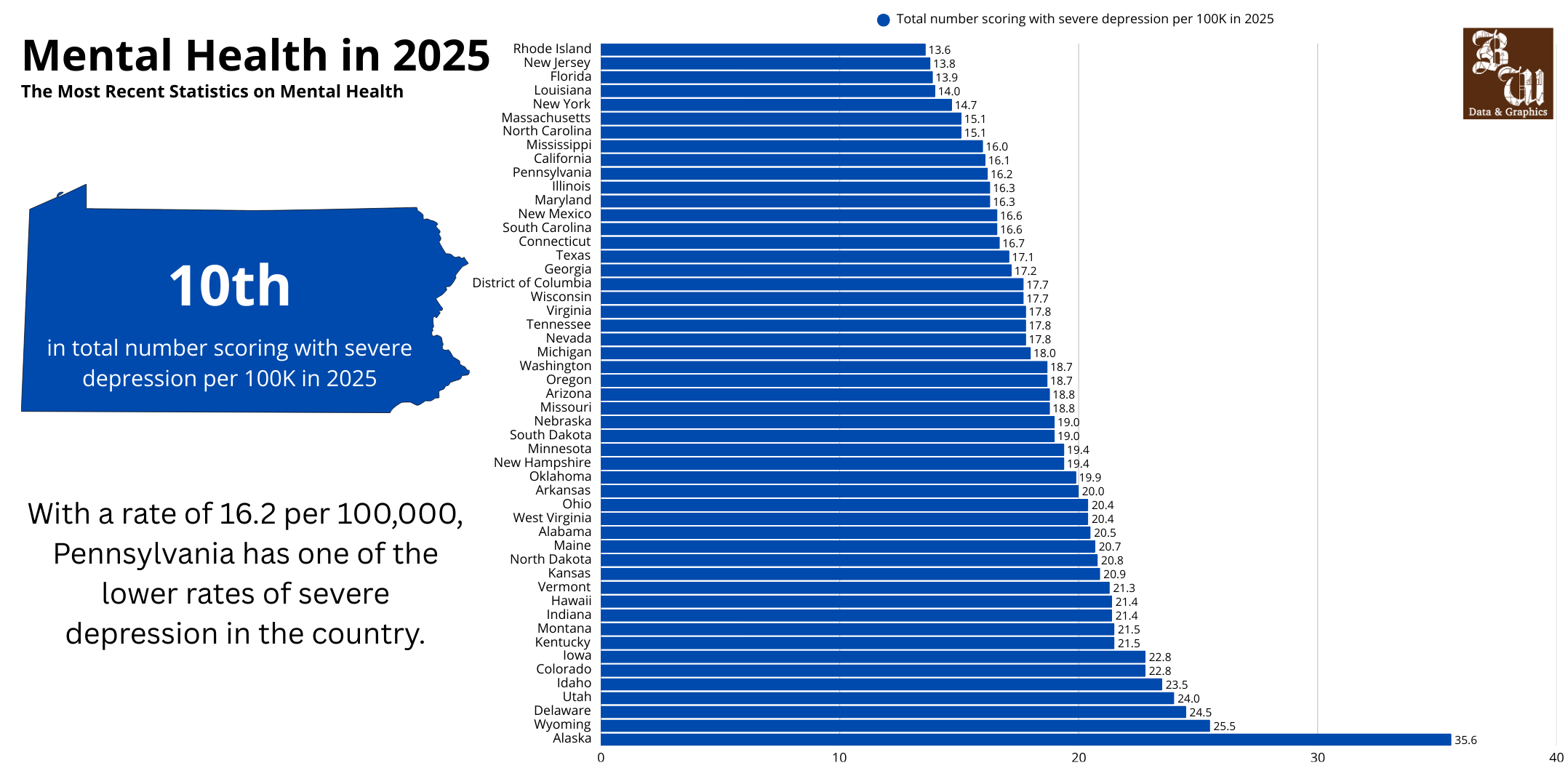

Graphic by Christopher Skabich · Source: Mental Health America

Graphic by Christopher Skabich · Source: Mental Health America

“When you look at those numbers, typically in December is usually our highest number of suicides,” he said.

Buglio also said toward the end of the year, most people who die by suicide in the county are 50 or older.

Andrew Anderson, an assistant professor of health policy management at Johns Hopkins University, helped conduct a study examining how adults experience and respond to mental health crises. Anderson’s responses were provided through an email interview.

Nearly one in 10 adults in the U.S. experienced an acute mental health crisis in the past year, according to the study.

Anderson defined a crisis as times when a person’s thoughts, feelings or behaviors were too much to handle and required immediate help to stay safe or function.

“Acute distress occurs when everyday stressors exceed available coping resources,” Anderson wrote. “These moments often reflect broader systemic issues, economic precarity, lack of access to behavioral health care, discrimination, loneliness and structural barriers that limit people’s ability to get help early.”

Pinebrook Family Answers offers services for people seeking mental health support, including out-patient psychiatric and counseling services, youth behavioral programs, family-based support and reentry programs for people returning to the community after incarceration. The Suicide Prevention Coalition is one of Pinebrook’s initiatives.

Carlos Gomez works as a supervisor with the coalition.

Gomez said insurance can act as a barrier to necessary care. While there’s a significant need for mental health support, he said allowable amounts from insurance companies have made it increasingly difficult for organizations to continue operating.

“(The allowable amount) is the amount that the insurance will pay a provider no matter what they bill,” he said. “A lot of times, it’s significantly less than what the provider charges, or even what services are really rendered to the patient.”

The allowable amount acts as a negotiated maximum, dictating the most a patient can be charged. While it protects the patient, it also limits what providers are paid.

Gomez said if a doctor spends 90 minutes with a patient, insurance may bill $500 for the visit, which may not cover the cost of care.

The provider may receive about $100 of that amount, he said.

“And if you take a look at the bigger picture, that’s not a lot of money, especially with providers’ time to prepare for their patients,” he said.

He also said everyone who seeks help has a different story. Some are seeking counseling, others medication from a psychiatrist, or support groups to discuss lived experiences.

Lori VanDoren, the vice president of programs at Pinebrook Family Answers, said alongside the nation’s mental health crisis is a shortage of mental healthcare providers. She said much of Pinebrook’s work is supported by medical assistants.

“Sometimes, what we get paid from the insurance companies don’t actually cover our costs as an agency, which can be difficult for us to keep operating,” she said. “Some organizations have closed because they couldn’t continue.”

She also said the Lehigh Valley is fortunate in some ways, as Lehigh Valley Health Network and St. Luke’s Health Network also provide mental health services, including psychiatry and outpatient care.

However, wait times remain long. VanDoren said the waitlists at the offices she connects people to through National Alliance on Mental Illness Lehigh Valley range from eight to 12 months.

In those cases, Murphy said she looks to pivot.

She encourages prospective patients to speak with their primary care about prescriptions that may help alleviate physical symptoms associated with mental illness, such as lethargy.

These medications are typically selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, which help increase levels of serotonin in the brain.

National Alliance on Mental Illness and Pinebrook both offer peer and family support groups open to biological and chosen families. Murphy said it doesn’t matter which organization participants choose — she wants people to know the groups are safe spaces to share their experiences.

“A family member who attended the family support group once said to me, ‘I can’t believe I’m in a room of people who understand what it’s like to not be able to invite people over because you don’t want them to see the holes that your son has punched in the wall when he was in the middle of an episode of psychosis,’” Murphy said.

The goal, VanDoren said, is to provide interventions sooner.

Pinebrook and National Alliance on Mental Illness also train volunteers. VanDoren said Pinebrook’s volunteers receive training in mental health first aid and QPR, a suicide prevention program designed to assess suicide risk.

This is one of many reasons Murphy shares her story.

“(We) just help people know that they’re not alone,” Murphy said. “They’re not the only ones going through this struggle.”

If you or someone you know is experiencing a mental health crisis, please call 988. Click the following links for more resources on how to get help from NAMI Lehigh Valley and Pinebrook Family Answers.