Data collection

We conducted a cross-sectional study in Yogyakarta City, Indonesia, during October–November 2024. Yogyakarta City (hereafter called “Yogya”) is the capital of the Special Region of Yogyakarta Province with a population of 414,000. The estimated proportion of adolescents aged 15 to 24 years represents 15% of the total population22.

Based on the statistical assumption, we interviewed 439 adolescents who met two main criteria: aged between 19 and 24 years, living in Yogyakarta and the surrounding areas (but still in Yogyakarta Province), and and was doing outdoor activities at that time. We conducted the interview outdoors. The interview was conducted by 6 trained enumerators using KoBoToolbox v2021.2.423 on a smartphone. We divided the data collection into three times of the day: morning, mid-day, and afternoon, with almost equal respondents in those three times of the day.

Participation was voluntary and all participants gave their informed consent prior to the interview. This study was approved by the Medical and Health Research Ethics Committee Faculty of the Faculty of Medicine, Public Health, and Nursing, Gadjah Mada University (Number KE/FK/1496/EC/2024). The research procedure was in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

The interview’s questionnaire consisted: (1) environmental conditions (interview time, ambient temperature, and humidity), (2) respondent’s characteristics (gender, age, education, etc.), (3) ecological conditions (green open space facilities, access to health care facilities, environmental policy, etc.), (4) microclimatic perception and preference (regarding ambient temperature, humidity, airflow, sunbeam, and comfort), (5) impact of heat exposure on physical and mental health, (6) the respondent’s mitigation and adaptation practices, and (7) the related psychological factors. We used the Likert scale for most of the psychological-related questions. Items, statements, or questions that were used in the statistical analysis can be found in Tables 1 and 2.

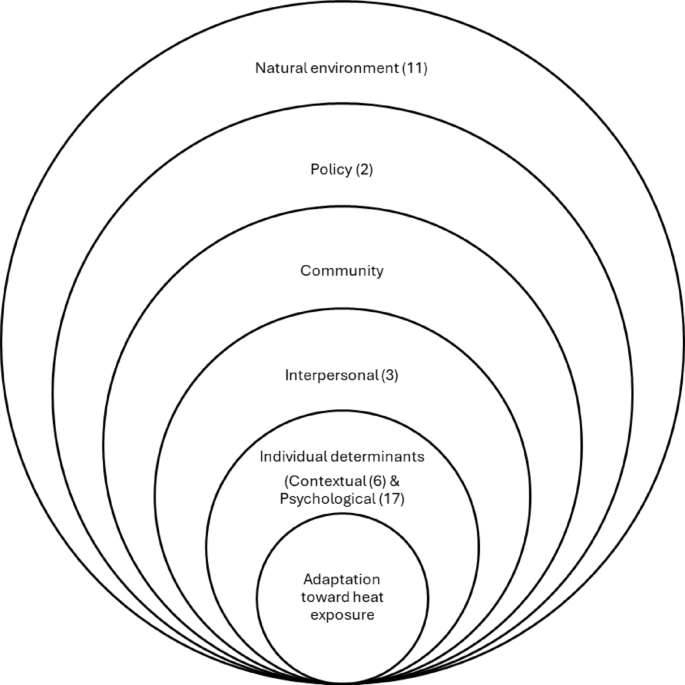

For the questionnaire, we adapted the Socio-Ecological Model (SEM) framework (Fig. 1)24 in combination with the RANAS theory at the individual level25. The SEM framework argues that individual behavior is influenced by the interplay of multi-level aspects, i.e., individual, interpersonal, community, policy, and natural environment. Items, statements, or questions from the surveys were then grouped into those five aspects. Examples of individual factors are age, gender, education, and the impacts of heat exposure experienced by the person. Examples of interpersonal factors are the negative impacts related to heat exposure that is experienced by the respondent’s relatives or peers, the frequency of talking about adaptation practices toward heat exposure with peers, and the frequency of hearing about the impact of heat exposure on health. An example of community factors are the social norms. To measure the policy factors, we collected people’s perceptions about government policies to create a cooler environment and whether the government provided information about the impact of exposure to a hot environment. For the natural environment, we included questions on microclimate perceptions, temperature, and humidity.

An adapted socio-ecological model of adaptation towards indoor heat exposure. The values indicate the number of variables used in the statistical analysis. The ‘community’ aspect-related variables are analysed under the individual–psychological determinants.

We measured ambient temperature and humidity, each time before an interview was conducted with each respondent, using the Air quality monitor HT9600 particle counter, Digital humidity & temperature meter GM1360A, and AZ 87,786 WBGT logger.

Data analysis

Data from KoboToolbox was transferred to Microsoft Excel for cleaning, and afterwards to IBM SPSS version 27 for statistical analysis. All data are presented as mean (M) and standard deviation (SD).

For the impacts of heat exposure, we enquired about the physical and mental impacts experienced by the person. There were 10 and 8 items related to physical and mental impacts, respectively. The questions that we asked are: “Have you ever experienced symptoms related to heat exposure?” and “How do you feel when the weather is very hot?”. Examples of physical impacts are fatigue, dehydration, excessive sweating, heat stroke, etc. Examples of mental impacts are stress, sleep disturbances, confusion, anxiety, etc. We summed up all items, and the level of physical and mental impacts experienced by the respondent was determined from the number of items mentioned (i.e. more items relate to a higher level of impact).

For the microclimate perceptions, we enquired about their perceptions of the present temperature, humidity, wind flow, and overall comfort with the environment situation. We used 5–7 Likert scale answer options.

We analysed the norms-related variables (‘community’ aspect or layer in the SEM model, Fig. 1) at the individual aspect because these norms-related variables are included in the RANAS theory at the individual aspect. According to the RANAS theory, the behavioral determinants can be divided into contextual (age, income, education, etc.) and psychological factors (perceptions of risk, attitude, norms, etc.). We adopted the approach of existing RANAS studies that analysed first the contextual factors, and significant contextual factors were included in the final regression analysis using psychological factors26,27.

For the dependent variable in the regression analysis, we used a question about the adaptation practice that the respondent did at the time of the interview. In this study, we define adaptation as an action taken to manage and minimize the impact of heat exposure. There were 11 items related to heat adaptation practices, e.g., Use head protection, sunglasses, sunscreen, wear appropriate clothing (light, loose, and light-colored), bring drinking water when outdoors, consume sufficient drinking water to prevent dehydration, limit activities under direct sunlight, etc. We summed up all actions that were mentioned by the respondent, and the engagement level in adaptation practice towards heat exposure was determined from the number of actions mentioned by the respondent (i.e. more actions related to higher engagement in adaptation practices).

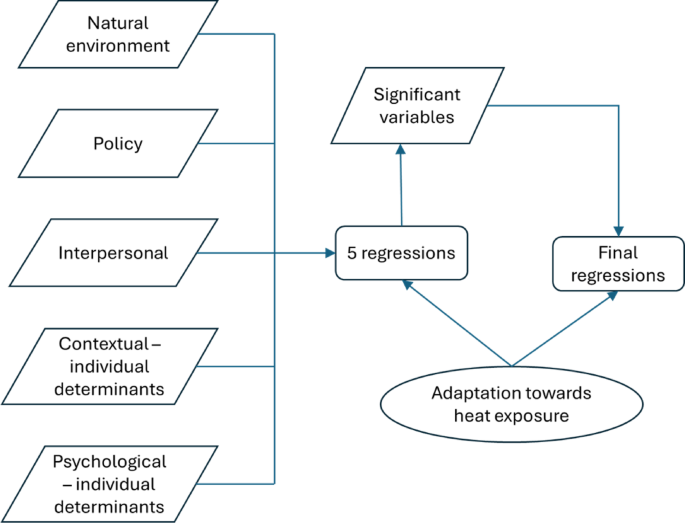

We performed the stepwise multivariate regression analysis using all variables. First, we entered all variables in each aspect and regressed them on adaptation practices, as the dependent variable. For example, we entered 11 variables in the natural environment aspect as independent variables and regressed them on adaptation practices. Significant variables (p-value < 0.05) in this regression were then included in the final regression. We repeated the same procedures for other aspects of SEM. The procedure is shown in Fig. 2.

Procedure of the analysis. Parallelogram boxes are the independent variables, and an oval box is the dependent variable.