Families say they’re watching their loved ones deteriorate in jail while lawmakers struggle to fix a mental health system built for a much smaller state.

SPALDING COUNTY, Ga. — Jails are built to hold people accused of crimes — not to treat serious mental illness. But across Georgia, hundreds of people ruled incompetent to stand trial are sitting in them for months, often more than a year, waiting for a bed to open at the state’s mental health hospital.

Lawmakers are confronting the issue as they debate the state budget. Commissioner Kevin Tanner, who oversees the state agency that runs the hospitals, told lawmakers there are currently about 800 people in Georgia jails waiting for transfer to a state hospital for competency restoration treatment.

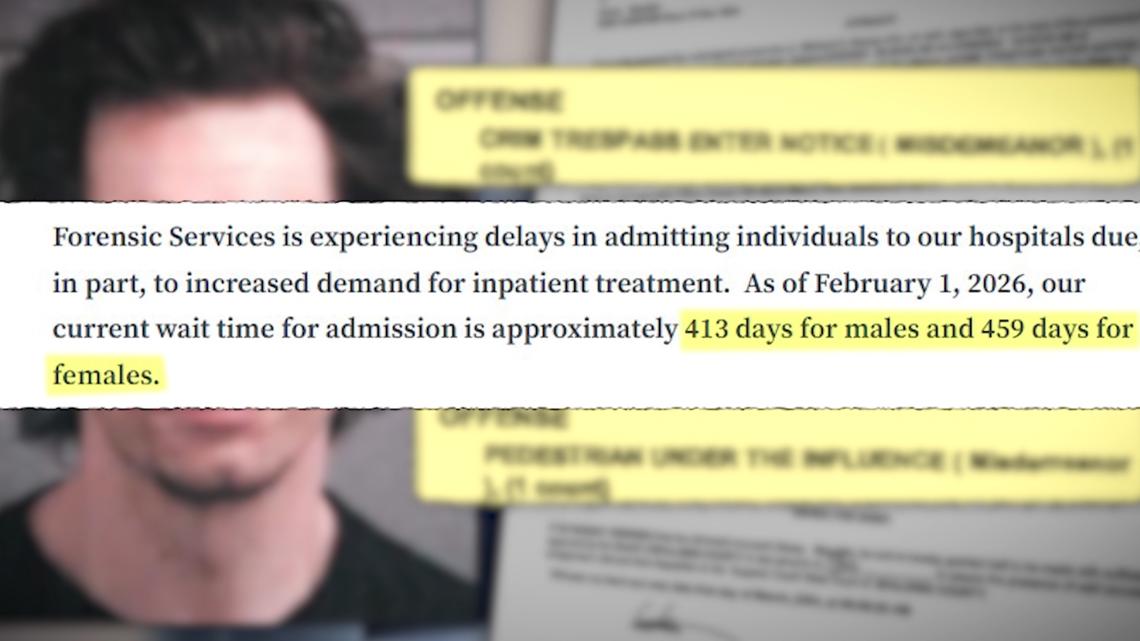

Korey Mauldin is one of them. Court records show a judge ordered he be transferred to the state hospital more than a year ago. Instead, he has remained in the Spalding County Jail.

Disciplinary records provided by his sister, Kayla Sanders, document repeated incidents while he has been in custody: being tased, placed on lockdown, isolated after fights with inmates and guards, and placed on suicide watch. On one occasion, he repeatedly banged his head against a cell door for hours. In another, he was found pulling padding off the wall in an isolation cell and eating it.

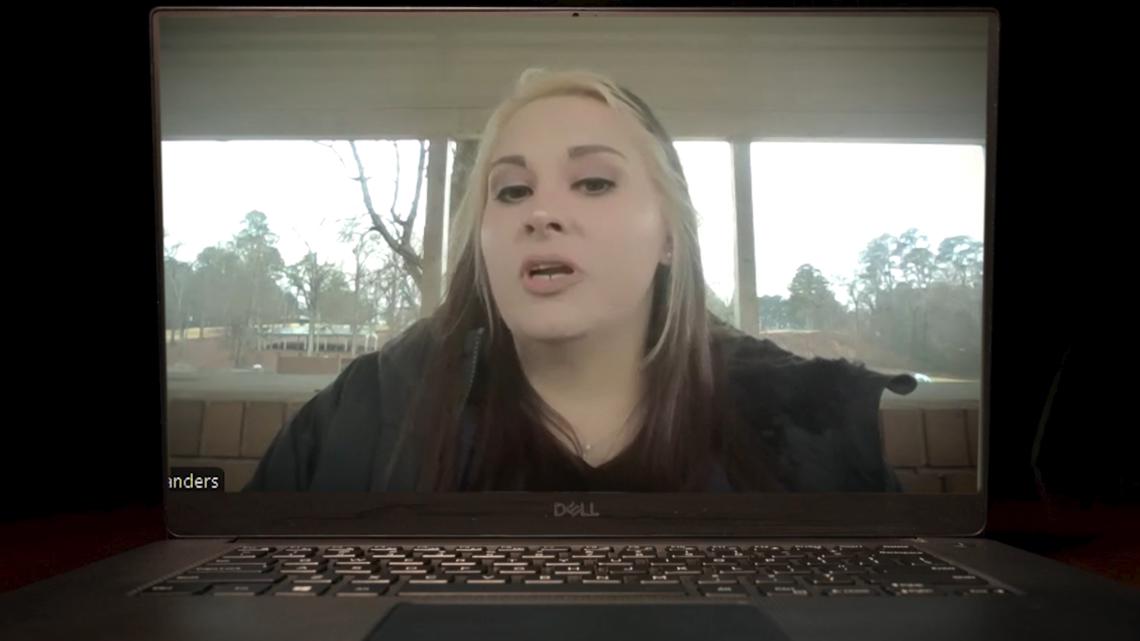

“You want to be angry at the jail. You want to be angry at the staff, but they’re overwhelmed. They’re overworked. They’re underpaid. It’s hard,” she said.6;’

Still, Sanders says she can see her brother’s health decline during video visits.

“He’s sitting in that jail without mental health treatment. His body is deteriorating. His mind is deteriorating. He’s not receiving, as far as my knowledge, the proper treatment that he should be,” said Sanders.

Sanders shared his records and agreed to talk with 11Alive Investigates, in a desperate hope to raise awareness about his case and the need for him to be transferred.

“He’s my heart. He’s my younger brother. One out of two. He was a mama’s boy. Very giving, kind, always trying to help others,” said Sanders.

Under Georgia law, when someone is arrested and later found incompetent to stand trial, a judge orders them transferred to a state psychiatric hospital. There, doctors determine whether medication and therapy can restore the person’s mental health so the criminal case can move forward. If not, the charges may be dismissed or the person may be involuntarily committed for long-term care.

Mauldin is jailed on misdemeanor charges including trespassing, loitering and public intoxication. In cases like his, a person can spend more time behind bars waiting for mental health treatment than they would have if they had simply been found guilty and sentenced on the original charges.

Sanders says she does not want her brother released. She wants him transferred to a facility where medical staff are trained to treat his condition.

“These jailers, these police officers, these deputies, they’re not trained to handle these cases. They’re not trained to handle these mental health diagnoses. That is never what jail was supposed to be,” said Sanders.

According to the state, the current average wait time for a male to be admitted to the state hospital for competency restoration is 413 days. The wait is even longer for females, 459 days.

Beds only become available when someone leaves the program. As more people are sentenced to state custody for serious crimes, fewer beds open up for those waiting in jails for restoration treatment.

Lawmakers questioned state officials about why years of additional funding for new beds and recruiting staff have not solved the backlog. State leaders told lawmakers that a certain percentage of the population will always require this type of care, but Georgia’s system was originally designed to serve a population of about four million people. Georgia now has more than 11 million residents.

The Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities is building a new 40-bed unit, but construction takes time. Even when it opens, the additional beds will be a fraction of what is needed.

For families like Sanders’, the timeline for solutions does not match the urgency of the crisis.

People like her brother, she says, need help now.

“Because his life matters. He’s important and he’s worth it.”