Around 75 per cent of all suicide deaths in Canada are men — yet plenty of stigma remains around men’s mental health concerns, according to the Canadian Mental Health Association.

That’s why the Windsor and Essex County branch of the CMHA is continuing its Healthy Minds 4 Men program, the next edition of which launches in late February.

The free four-week course offers guided group sessions where adult males are able to explore their emotions, show vulnerability and learn about mental health in a non-judgmental environment.

“We know that men should reach out for help more. We encourage it,” said Adrian Deschamps, a mental health educator with CMHA Windsor-Essex, who designed the program last year.

“But a lot of men, even though they see this invitation — deep down, they still feel that fear of reaching out.”

Adrian Deschamps, a mental health educator with the Windsor-Essex branch of the Canadian Mental Health Association. (CBC News)

Adrian Deschamps, a mental health educator with the Windsor-Essex branch of the Canadian Mental Health Association. (CBC News)

Despite many public awareness campaigns and efforts to normalize talking about mental health, Deschamps says avoidance and self-isolation remain the most common response among men when confronted with emotional challenges.

“It’s one of those things were I can sit with a group of guys, and I can say, how many of you have been told real men don’t cry? And every hand goes up,” Deschamps said.

“How many of you have been told that if you show weakness or show vulnerability, that you’re not going to be respected? Every hand goes up.”

The sign at the Windsor-Essex branch of the Canadian Mental Health Association. (CBC News)

The sign at the Windsor-Essex branch of the Canadian Mental Health Association. (CBC News)

Each of the four sessions of the Healthy Minds 4 Men program is meant to examine a different area of men’s mental health.

For example, the first session delves into male-specific stressors, such as social dynamics and societal pressures.

Deschamps says economic factors and traditional “provider expectations” can put men “in a really bad headspace,” especially when it comes to employment and the workplace.

“Workplace mental health is one of the biggest areas that can be overlooked,” Deschamps said. “We often spend a lot of our waking life at work, right? If you’re going to work for seven, eight hours a day, and you’re walking in with a sense of dread and a sense of stress, it’s going to affect you.”

Mental health educator Adrian Deschamps at the Windsor-Essex branch of the Canadian Mental Health Association. (CBC News)

Mental health educator Adrian Deschamps at the Windsor-Essex branch of the Canadian Mental Health Association. (CBC News)

According to CMHA data, in 2022, there were 3,589 suicides in Canada — and 2,686 of them were male. Deschamps says the most represented age group among those male suicides was 44 to 64 years old.

Asked why there is continued reluctance to engage men’s mental health concerns, generation after generation, Deschamps says he believes there’s a difference between understanding an issue with one’s head and understanding with one’s heart.

“We’re often fighting through the emotional component, more so than the cognitive component, of understanding what to do,” he said.

Melissa Bianchi (left) and her son Jacob Lamont (right) in a personal photo. (Melissa Bianchi)

Melissa Bianchi (left) and her son Jacob Lamont (right) in a personal photo. (Melissa Bianchi)

That may have been the case with Jacob Lamont — a 24-year-old Windsor man who died of a fentanyl overdose in June 2023.

Lamont’s mother, Melissa Bianchi, says her son was not a regular user of fentanyl, but she doesn’t know if he meant to take his own life. He had struggled since childhood with anxiety, depression and suicidal ideation.

“I used to make him promise me: One more day,” Bianchi said. “I would know when he was having a bad moment, a bad day, a bad week. And I’d say: ‘Just promise me one more day.’”

“And I remember him laughing at me and saying, ‘Yeah, and then what happens, Mom, with one more day? If I feel the same?’”

“And I’d say, ‘Then you promise me one more, Jacob.’”

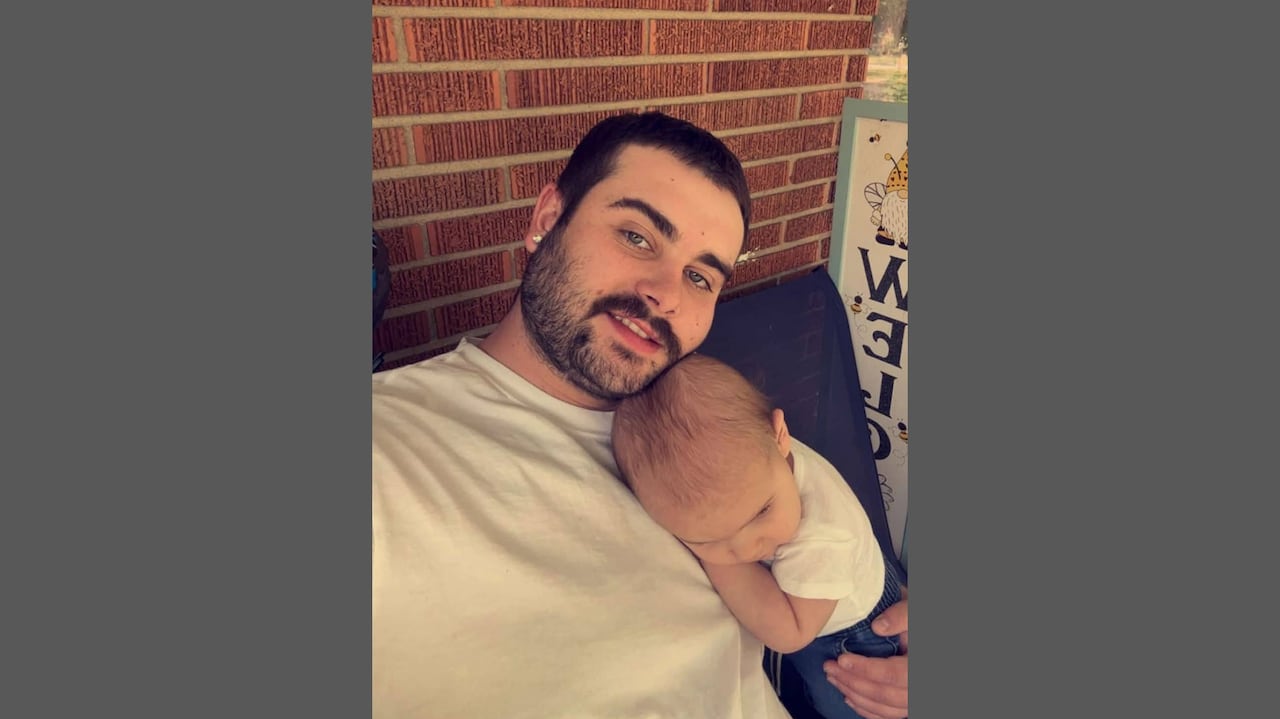

Jacob Lamont of Windsor with his infant son in a personal photo. (Melissa Bianchi)

Jacob Lamont of Windsor with his infant son in a personal photo. (Melissa Bianchi)

Bianchi says that at the time of her son’s death, he was dealing with “monsters in his head” — despite the fact that he had loving family members, and had recently become a father.

She believes her son would have benefitted from programs like Healthy Minds 4 Men, as well as better public understanding of men’s mental health.

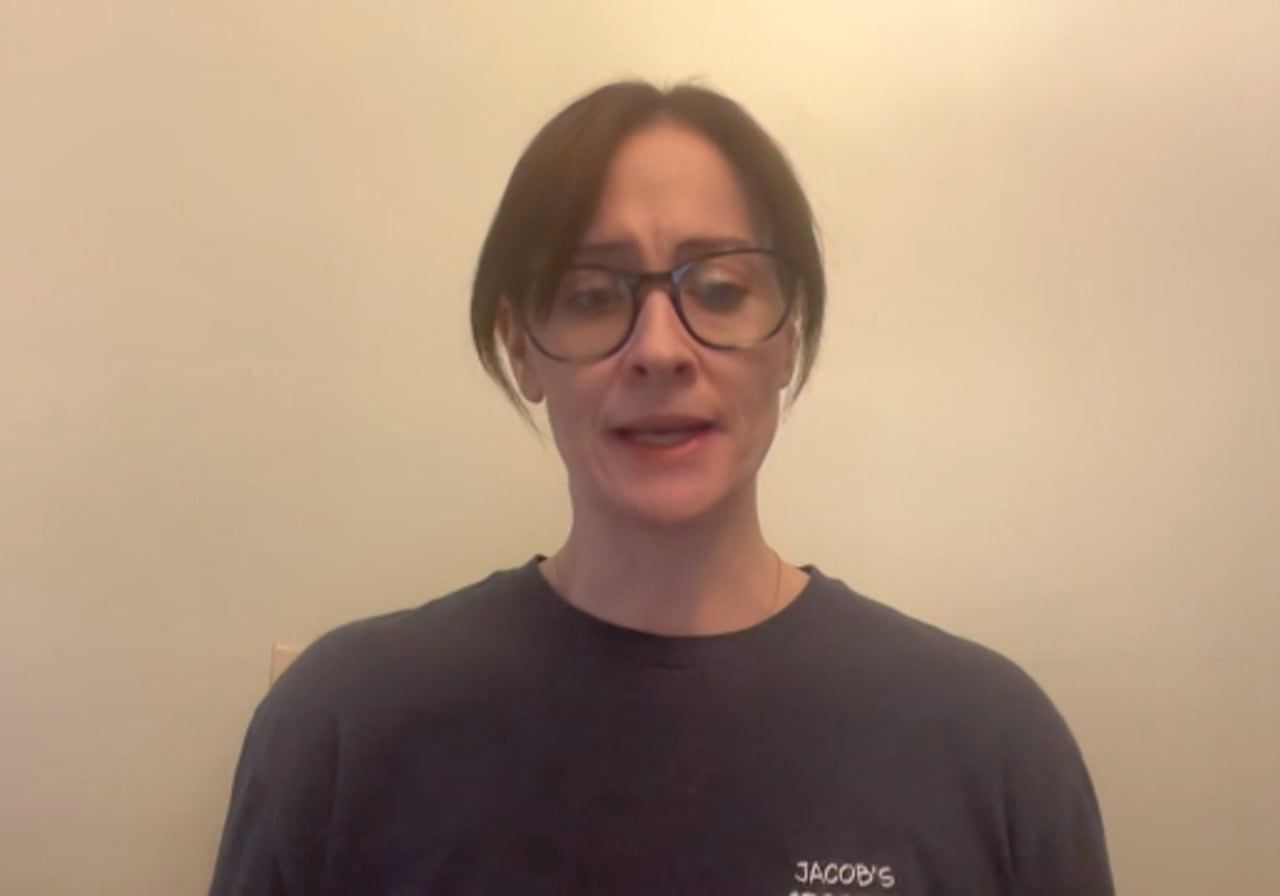

Melissa Bianchi, mother of Jacob Lamont, speaking with CBC Windsor. (CBC News)

Melissa Bianchi, mother of Jacob Lamont, speaking with CBC Windsor. (CBC News)

“I think that there is such a stigma around it that it creates a silence, and I think that that silence is deadly,” Bianchi said.

“When you talk about men’s mental health, or when they try to open up, there’s an embarrassment. There’s shame. There’s fear of being judged. It’s not good enough. It’s not being manly enough. And I know my son struggled with that.”

Jacob Lamont of Windsor in a family photo. (Melissa Bianchi)

Jacob Lamont of Windsor in a family photo. (Melissa Bianchi)

The 2026 edition of Healthy Minds 4 Men begins 6 p.m. on Feb. 24 at the Windsor-Essex branch of the Canadian Mental Health Association (1400 Windsor Ave.).

Enrollment is free, but advance registration is required. To register, visit the events section of windsoressex.cmha.ca.

If you or someone you know is struggling, here’s where to look for help: