David Hosford is anxious about a big test coming up in December. That’s when the 87-year-old retired high school teacher will have his driving skills assessed to see if it’s still safe for him to get behind the wheel.

Hosford was diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment about four years ago but seemed OK to drive. Recently, though, his neurologist had grown concerned about some deterioration and suggested Hosford take a safety test and stop driving until that evaluation was completed.

So for now Hosford and his wife, Diana, who does not drive, are relying on neighbors and friends to take them to appointments, shopping, and everywhere else they need to go. The wait time for back-logged safe driving assessments can be several months in Massachusetts.

“We live out in rural Plymouth. The nearest loaf of bread is seven miles down the road,” Hosford said. “There isn’t any place to walk to.”

Determining whether an older person remains safe to drive has become a third rail of aging as many people maintain their license far longer than most did a generation ago. At the same time, the proportion of fatal crashes nationwide involving older drivers has risen 73 percent since 2001, federal data show. Now, two new studies from local researchers underscore the challenges ahead.

“Most health care professionals do not have the requisite knowledge and training to assess driving competence,” Dr. Kirk Daffner, director of the Center for Brain/Mind Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, noted in an October article in JAMA Neurology.

Daffner sees many patients with cognitive impairments who may eventually need a comprehensive driving assessment by a specialized program, which often includes a road test. But many, like Hosford, struggle to pay the hefty price tag, which can run upward of $800 in Massachusetts.

Medicare doesn’t cover the cost, which means millions of older adults, many on fixed incomes, must come up with the money. This policy, Daffner wrote in JAMA, needs to change.

“Impaired drivers,” he wrote, “pose safety risks for not only themselves but also the public at large.”

But just yanking older drivers’ licenses should not happen in a vacuum, Daffner said, because it often leads to isolation.

“If we take away people’s keys or the ability to drive, then as a society we need to do a better job providing them with alternative means of transportation,” he said. “It’s just cruel to say; ‘Well, you can no longer drive, and good luck.’”

And while the number of fatal crashes involving older drivers has increased in recent years, the number of those crashes as a share of the older population has declined.

Still, Daffner and other health experts said they see trouble ahead.

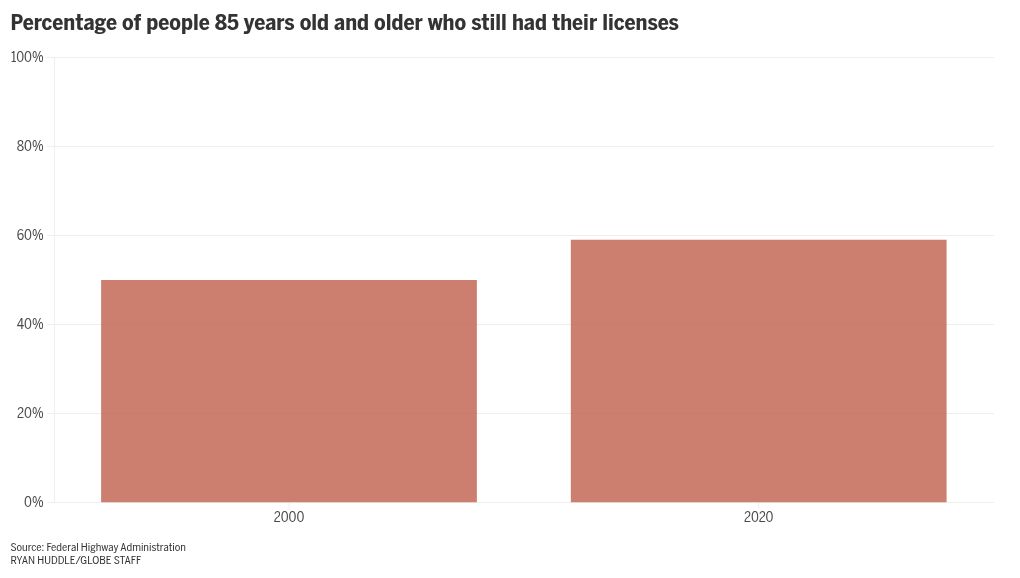

More drivers than ever are maintaining their licenses well into old age. Federal data show that 59 percent of people 85 years and older still had their licenses in 2020, the most recent data available, compared with roughly half in 2000. And about 17 percent of Americans over 65 — about 8.2 million people nationwide — experience mild cognitive impairment and are at increased risk for crashes.

Age alone doesn’t determine driving performance. But as our years increase, so, too, does the potential for health issues that can impair ability behind the wheel, including reduced vision or hearing, slower reaction times, seizures, or heart conditions that can produce light-headedness.

Andrew Zullo, an associate professor of public health at Brown University, recently studied medications commonly taken by older adults that could impair driving ability, such as medicine to treat anxiety, insomnia, pain, depression, and even high blood pressure, and found that most who were in a car crash continued to take them afterward.

Zullo’s study, published this month in JAMA Network Open, noted that approximately 20 percent of drivers 65 and older who have been involved in one crash will have another. That sobering statistic, he said, makes it crucial for health leaders to identify ways to prevent these crashes.

One obvious obstacle, he said, is that doctors often don’t know their patients were involved in an accident unless they were seriously injured.

“We don’t have robust systems in the US to notify physicians,” he said. If doctors had such a system, or their patients felt comfortable confiding the information, their doctor could do a review of their medications and perhaps lower the dosage or switch to another one with less potential to impair driving.

“I think a lot of older adults are worried if they are involved in a motor vehicle crash their families or others in their lives may express concern about their driving and may apply pressure to stop driving,” Zullo said. “That’s a worry for older adults because that’s taking away their autonomy.”

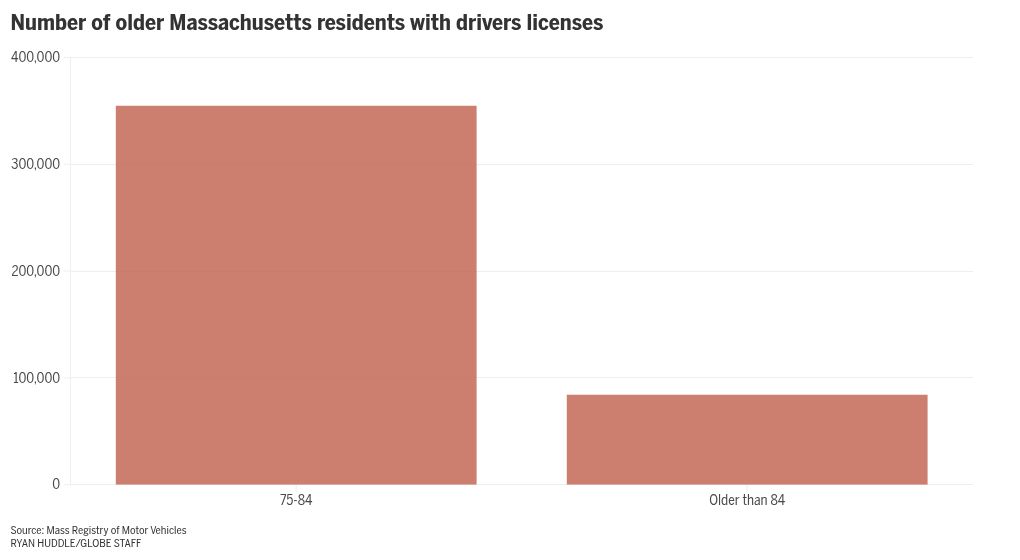

Massachusetts law requires people 75 and older to renew their license in person and pass a vision test. But after they’ve passed the road test required to receive a license in the first place, often decades ago, the state relies on motorists themselves to determine whether they can still safely drive. It does not require health care providers to report patients they believe are not physically or medically capable of safely operating a motor vehicle, though it provides a system to report concerns to the Registry of Motor Vehicles, which has a medical affairs unit to review the reports.

Dr. Sarah McGee, clinical chief of geriatric medicine at UMass Memorial Health, said in her 34 years at UMass, she has resorted to reporting just one or two patients to the state. But she said she strongly advises patients who may be impaired to have their driving evaluated by an assessment program, explaining where the programs are and how much they cost.

Sometimes driving assessments find a patient may just need a refresher course, she said, and they set up a lesson.

“Some patients say, ‘I do much less driving at night,’ or ‘I don’t like driving in a storm,’ or they don’t like getting on a highway,” McGee said. “It’s very telling in terms of what people share with you. A lot of times people will restrict their driving themselves.”

Often caught in the middle are middle-aged children of older people, nervously watching a parent decline but unsure how to broach the prickly issue.

That would describe Anna Stern, a 45-year-old social worker who realized her then-76-year-old mother was driving around Somerville far below the speed limit, changing lanes without signaling, and seeming uncertain behind the wheel. Stern contacted her mother’s doctor privately and asked that he bring up the subject.

Her mother, who thought her driving was fine, didn’t pass the initial in-office evaluation at Spaulding Rehabilitation, one of a handful of hospital-based driving assessment programs in Massachusetts. So she opted not to proceed to the road test and gave up her car.

“I was shocked,” said Stern’s mother, Tam Neville, now 80. “I studied the AAA book, and I thought it would be easier than it was. My feeling is that they don’t want seniors on the road, probably for good reason.”

Neville is among the fortunate ones. She could easily afford the $300 for the initial evaluation, and she lives within a 10-minute walk of many stores and restaurants in Somerville. She also has a home health aide to help run errands.

David and Diana Hosford’s wedding photo. The retired Army veteran, who was awarded the Bronze Star for his service in Vietnam, was diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment and his neurologist wants him to take a driving test.

Craig F. Walker/Globe Staff

But Hosford, the 87-year-old awaiting his driving evaluation in Plymouth, isn’t so lucky. With a fixed income, the $300 tab on his credit card weighs heavily as he looks longingly at his idle Ford pickup truck.

“I feel like a beggar when I have to ask friends and neighbors for a ride,” he said.

Losing the ability to drive, said his wife, Diana, is like breathing. “You don’t think about it until you can’t.”

Kay Lazar can be reached at kay.lazar@globe.com Follow her @GlobeKayLazar.