Anxiety affects hundreds of millions of people every year. What treatments are available, and how have they changed over time?

Anxiety is the most common mental health condition globally. It’s estimated that 4% to 5% of people in the world have an anxiety disorder at any given time.

Long-term surveys in the United States suggest that around one-third of people experience an anxiety disorder at some point in their lives.1

There is often poor data on the prevalence of mental health conditions, especially in lower-income countries. Even in rich countries, these figures might be an undercount due to the stigma that many feel in admitting they struggle with mental health.

That means most of us will either struggle with anxiety ourselves or know someone close who has or will. This is also true for the two of us, and seeing how big an impact it can have on people’s everyday lives, we know that having effective treatments that alleviate or at least reduce symptoms can be life-changing.

In this article, we examine the history of pharmacological treatments — specifically, drugs — used to treat anxiety since the 1950s. These have changed a lot in the five decades until the early 2000s, but there have been no new anxiety medications approved since 2004.2

While there has been a slowdown in the number of new drugs approved for anxiety (which is the focus of this article), the usage and number of prescriptions for anti-anxiety medications have likely continued to increase in recent decades.

It can be hard to get concrete and consistent data on this because, as we’ll see, many of the most recent drugs are primarily antidepressants; so even when prescription figures are available, it’s usually not clear whether they are being used to tackle depression or anxiety. In some cases, it can be both. Even in just the last few years, there have been noticeable increases in the percentage of American adults receiving mental health treatment, which includes taking medications.

For context, around one in six American adults takes medication for any mental health issue each year.

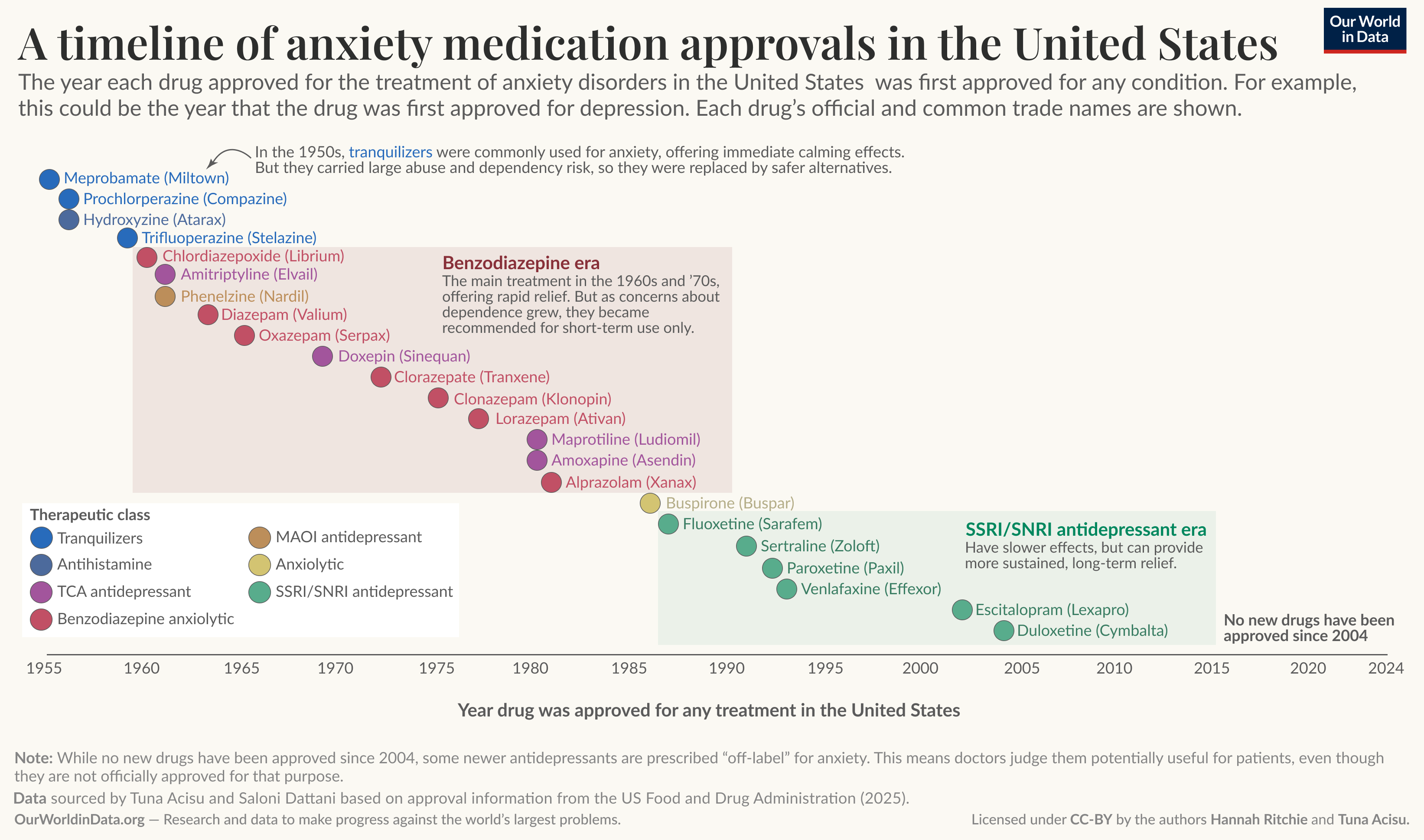

Across the world, a range of treatments are used to alleviate anxiety. Building a consistent timeline for all countries would be difficult, so here we focus on the timeline of medication approvals in the United States. At least 22 drugs have been officially approved for anxiety treatment there since 1955.

In the chart below, we’ve created a timeline. Each dot represents a single drug, with its official name and trade name (which you may have heard more about) labeled. Tuna Acisu and Saloni Dattani produced this dataset based on data from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).3

Most of us will either struggle with anxiety ourselves or have someone close to us who has or will.

The date allocated to each drug is when the FDA first approved it. This means the FDA found the molecule to be a safe and effective treatment for a particular condition. Some of these drugs were first approved explicitly for anxiety, but others were used for other conditions and were only approved for anxiety later. For example, “duloxetine” was approved for the treatment of depression in 2004, which is the date shown on the timeline. It got licensed for anxiety three years later.

Each drug is colored according to its therapeutic class, determined by its active ingredient and mechanism of action in treating anxiety.

Note that here we only focus on drugs officially approved for anxiety treatment by the FDA. That means “off-label” medications — which means a doctor decides that a particular drug could be useful for a patient, despite it not being officially approved for anxiety — are not included.

The timeline can be split into three big parts: tranquilizers in the 1950s, the benzodiazepine era up to the mid-1980s, and the era of antidepressants in the following two decades.

The first medication on our timeline is meprobamate, commonly known as Miltown. It’s a tranquilizer, which was the main treatment for anxiety in the 1950s. Miltown has often been framed as the first “blockbuster” psychiatric drug in the United States, due to its popularity and how it was promoted to “consumers”.4

Several historical accounts of anxiety treatment suggest that 1 in 20 Americans was taking Miltown in the late 1950s, but we were unable to find an official or academic source for these claims.

Miltown was marketed as a “minor tranquilizer”: it was said to take the edge off anxiety symptoms without the full effects of sedation that previous tranquilizers caused. It worked by slowing activity in the central nervous system, often reducing the acute symptoms of anxiety.

While it was safer than previous drugs, it still carried significant risks of overdose and addiction and was later replaced by safer treatments.

In this era, anxiety was often treated as a short-term nervous reaction. That’s why treatments like tranquillizers were used: they targeted the physical symptoms of the nervous system rather than the underlying causes.

But as you can see in the timeline, antidepressants, such as monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) started being used in the early 1960s. These can alter the patient’s mood and affect their anxiety by changing brain chemistry. Their effectiveness suggested that anxiety had a neurological basis that could be changed in the long term through medications, rather than relying only on short-term treatments that targeted nervous symptoms. This represented a clear change in the overall scientific understanding of anxiety disorders.

The benzodiazepine revolution of the 1960s and ‘70s

The major treatment revolution of the 1960s and ‘70s was in the development of benzodiazepine anxiolytics.5 In the timeline above, you can see them in the red box. These became the go-to anxiety treatment for decades. Valium and Xanax are two of the most well-known drugs in this class.

Anxiolytic is the technical term for drugs that reduce anxiety. Other drugs that don’t have “anxiolytic” in their name, such as antidepressants, can also have an anxiolytic effect. It’s just not included in their drug class.

Benzodiazepines work by enhancing the effect of GABA, the brain’s main calming neurotransmitter. By amplifying this neurotransmitter, these drugs reduce brain activity, producing relaxation and relief from anxiety.

A crucial feature of benzodiazepines is that they can work very quickly, reducing symptoms within hours or even minutes. That’s very different from many antidepressants, which can take weeks to have an effect.

Many studies on benzodiazepines have found positive results in reducing symptoms compared to a placebo.6

Benzodiazepines are often effective in treating acute physical symptoms such as panic attacks, but do not necessarily provide a long-term solution.

The main concerns with these drugs are tolerability, abuse, dependence, and withdrawal symptoms.7 Growing concerns about these problems led to them falling out of favour among many clinicians, especially with the arrival of SSRI antidepressants.5 Their use for anxiety has declined in the late twentieth century, even though some argue that benzodiazepines can be just as effective and tolerable for many people as the drugs that followed.8

The use of antidepressants since the 1990s

In the late 1980s, a new generation of anxiety treatments was born: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). You can see them in the green box in our timeline.

SSRIs were initially introduced to treat depression, but were also effective across several anxiety disorders. They work by blocking the reabsorption of serotonin — a “messenger” in the brain that plays a key role in mood regulation, anxiety, and sleep — so that more of it remains available.

When someone struggles with an anxiety disorder, the amygdala in the brain (their “fear alarm system”) tends to be overactive, while their prefrontal cortex (which helps to regulate that fear) is underactive. When SSRIs increase serotonin availability, they reduce the noise from the amygdala and strengthen the prefrontal cortex to regulate emotions of fear. That can reduce anxiety symptoms and panic responses.

Many studies show that SSRI antidepressants are effective in treating anxiety disorders. A Cochrane Review, which included 37 studies focused on “generalized anxiety disorder”, concluded that they “have high confidence that antidepressants are more effective than placebo at improving treatment response”.9

Cochrane Reviews are often seen as the “gold standard” of meta-analyses and medical literature reviews. It’s rare for them to suggest positive results with “high confidence”.

Other large meta-analyses have found similar results for the treatment of general anxiety disorder.10

SSRIs have also been shown to help with more specific anxiety disorders, such as social anxiety, but with smaller benefits.11 A different Cochrane Review found that they were effective in treating social anxiety relative to a placebo, but this was based on “very low‐ to moderate‐quality evidence.”12 This gives us lower confidence than the Cochrane Review on treating generalized anxiety disorder, which was based on higher-quality evidence. Still, it does suggest SSRIs likely have some positive impact on social anxiety, too.

One key reason why doctors are much more likely to prescribe SSRIs over benzodiazepines is that they don’t have the same potential for abuse and dependency. Unlike previous treatments, which often had a more acute and immediate effect, SSRIs tend to act more slowly. It can frequently take a month or more for people to feel the positive impacts on their symptoms and mood. However, they tend to be more sustainable, long-term solutions, meaning people can safely take them for longer, compared to previous drugs.

Some of the most commonly prescribed medications for anxiety today are SSRIs approved in the 1990s. We both know several people who have taken sertraline (Zoloft) to manage their symptoms, for example.

A similar drug type, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), also became available in the 1990s and early 2000s. They block the reabsorption of serotonin, but also block another neurotransmitter called norepinephrine. This can improve the patient’s energy levels, motivation, and focus — key symptoms for someone struggling with anxiety.

The last new anxiety medication that was approved in the US was duloxetine, an SNRI. This was in 2004, more than two decades ago.

The timeline we’ve just walked through is specific to the US. But we’d find similar patterns for other countries, such as the UK or others in Europe. There would, however, be some differences, especially in the specific dates of approval. There are also some drugs approved in Europe — etifoxine is one example — which are not approved in the US, and vice versa. Citalopram is another example; it’s approved for panic disorder treatment in the UK, but is only used “off-label” for anxiety disorders in the US.

No new drugs have been approved for treating anxiety in almost twenty years. But these two silent decades don’t mean there have been no developments in the treatment of anxiety.13

First, there have been incremental changes in formulations and dosage regimes for existing medications. For example, the US FDA approved a delayed-release form of duloxetine — the last drug on the timeline — and an extended-release version of lorazepam, which was first approved in 1977. Europe provides another example, where the formulation Duloxetine Lilly was approved in 2014. However, these are adaptations of existing drugs rather than discoveries.

While existing treatments can be life-changing for some, we still have some way to go to develop effective treatments for everyone.

Second, some newer antidepressant drugs are also prescribed “off-label” for anxiety. This means doctors decide, based on their judgment, that a particular drug could be useful for a patient with anxiety, despite it not being officially approved for that purpose. There are a surprising number of these; we found at least twelve when working on this timeline. It’s worth noting that the lack of approval for anxiety specifically can have implications for their availability and affordability, as it can affect insurance coverage.

Third, several promising new drug innovations are at various stages of development and clinical trials.14 Some of these target the same pathways as SSRIs and SNRIs, but in improved ways. Others take entirely novel approaches. Not all of these will succeed and become key treatments outside of the lab, but it seems likely that at least some will.

Finally, there have been developments in non-pharmaceutical treatments in recent decades. This article focuses on drugs, but there is an increasing number of other approaches, including cognitive behavioral therapy, non-invasive neurostimulation, and virtual reality exposure technologies.

Despite these, it’s hard to dispute that progress in the last few decades has slowed relative to the previous 50 years. While existing treatments can be very effective for some people — in fact, life-changing for some — we still have some way to go to develop effective treatments for everyone who struggles with an anxiety disorder, and ensure these treatments are available to them.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Saloni Dattani for helping to prepare the dataset on which this timeline relies. Thanks also to Max Roser and Edouard Mathieu for their feedback and comments on this article and its visualization.

Continue reading on Our World in DataCite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this article, please also cite the underlying data sources. This article can be cited as:

Hannah Ritchie and Tuna Acisu (2025) – “Anxiety is one of the world’s most common health issues. How have treatments evolved over the last 70 years?” Published online at OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved from: ‘https://ourworldindata.org/timeline-anxiety-medications’ [Online Resource]

BibTeX citation

@article{owid-timeline-anxiety-medications,

author = {Hannah Ritchie and Tuna Acisu},

title = {Anxiety is one of the world’s most common health issues. How have treatments evolved over the last 70 years?},

journal = {Our World in Data},

year = {2025},

note = {https://ourworldindata.org/timeline-anxiety-medications}

}Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license. You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.

Tranquilizers

Tranquilizers