A six-year report into the Durham Regional Police Service (DRPS) raises concerns about how it handles officers’ claims of mental health stress and PTSD, experts say.

The heavily redacted report by the Ontario Civilian Police Commission, obtained by CBC News through a freedom of information request, says the DRPS “vigorously opposed virtually every application to the Workplace Safety Insurance Board (WSIB) for presumptive PTSD,” and fought claims of chronic mental stress.

These findings are concerning since people need timely interventions for mental health support, said Alec King, communications and public relations lead for the Canadian Mental Health Association Durham.

“When help is postponed, healing takes longer,” he said.

DRPS Chief Peter Moreira and the police board have said the report covers events that happened over six years ago, involving former board members and a senior command team that is no longer with the service.

Much has changed since then, and many of the report’s 33 recommendations are already in effect, Moreira and the board said — but questions remain about how the service now handles PTSD and mental stress claims.

It is not clear whether DRPS is still opposing officers’ mental health claims at the WSIB, as found in the report. While the board and Moreira both released statements on Tuesday describing changes since the period covered by the report, neither specifically addresses the report’s findings related to PTSD and mental health.

WATCH | Report into DRPS found bias in workplace harassment investigations:

Durham police ran a ‘poisoned’ workplace, years-long investigation finds

A report outlining a six-year long investigation into the Durham Regional police paints a picture of a toxic workplace, including failutres to address harassment and mental health concerns.

The report also says investigators found evidence the DRPS ran a “poisoned work environment” marred by bias in workplace harassment investigations, intimidation and dismissive attitudes towards mental health concerns.

There is a public perception that most police stress and mental health leave results from traumatic events they respond to for work, says Judith Andersen, an associate professor at the University of Toronto’s department of psychology who researches mental health of first responders.

But, she says research shows that a “huge proportion” of mental health leaves and burnout is from organizational stressors.

“Often, the instigator of the stress leave is from [an] internal organizational toxic workplace,” Anderson said.

Police, board voice concerns with claims process

At a Durham Regional Council meeting on Thursday, Garry Cubitt, vice-chair of the DRPS board, brought up ongoing concerns with the Supporting Ontario’s First Responders Act, passed in 2016.

According to the report, the legislation was intended to give first responders quicker access to mental health support and benefits by assuming their PTSD is job-related.

But boards across Ontario have felt the law places limits on how they can support officers who have PTSD, said Cubitt, who was not on the board during the period investigated by the report.

“For example, you couldn’t necessarily insist upon treatment or insist upon reports back from psychologists or insist upon return to work plans,” he said.

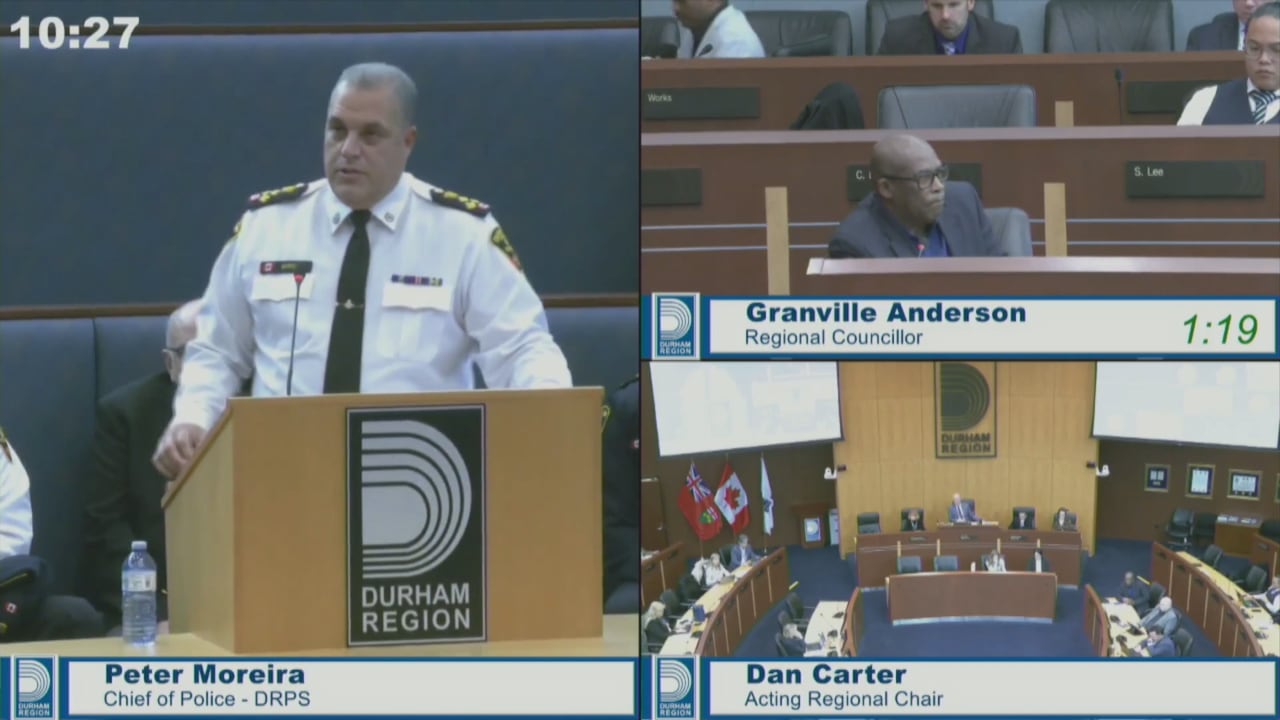

At a Durham Regional Council meeting on Thursday, DRPS Chief Peter Moreira said the current WSIB system has delays in getting the service the information it needs ‘to understand how we can best support our officers.’

At a Durham Regional Council meeting on Thursday, DRPS Chief Peter Moreira said the current WSIB system has delays in getting the service the information it needs ‘to understand how we can best support our officers.’

(Durham Region)

He said the board wasn’t being “vindictive or angry,” but members were concerned and wanted to get officers back to work as a positive step on their journey to recovery.

It is unclear whether the board is still dealing with these issues. Cubitt declined to speak with CBC News at the council meeting, and the DRPS board declined to comment further via email, instead pointing to its statement from Tuesday.

When service members return to their workplace, their reintegration is based on guidance from medical professionals, said Lisa Darling, executive director of the Ontario Association of Police Service Board (OAPSB).

“Boards have a responsibility to set expectations for member wellness, ensure systems and policies are in place to support physical and psychological health, and oversee the environment and culture of the police service,” she said in an emailed statement.

Meanwhile, Moreira said at Thursday’s council meeting that he has concerns about the WSIB program.

With the current system, he said it can take years for the service to get information it needs “to understand how we can best support our officers” and protect service members from danger and injury.

Moreira declined to speak with CBC News at the council meeting.

CBC News reached out to DRPS for comment. In response, DRPS provided links showing Ontario Association of Chiefs of Police (OACP) calls for WSIB reform dating back to 2021 at least.

The OACP, OAPSB and the Police Association of Ontario are all part of a group, supported by the WSIB, that is looking to improve how claims are handled, Darling said.

In a statement, Christine Arnott, a WSIB public affairs manager, said that “every organization has access to necessary information about injury claims filed, including online services available 24/7.”

The board regularly engages with police services on strategies to support officers in recovery, particularly related to mental health issues, Arnott’s statement says.

Returning officers to work is a priority, chief says

During Thursday’s meeting, Moreira said DRPS returned 114 members back to work last year after leave from the service, including five who had been off for multiple years. He did not say how many of these members were on leave related to mental health.

“Our program now is focusing not on what was in the report, but rather on getting members back to work as quickly as possible,” he said.

Andersen agreed it is important for officers to return to work — but long-term follow ups are important. “The true temperature test is to ask those individuals, in an anonymous way, what it’s like when they return,” she said.

Officers who return from mental health leave can face “an environment of distrust,” she said, such as colleagues who are unwilling to go out on a call with them.

“People don’t talk to them as much, they put them on desk duty,” she said. “They’re treated differently.”