Trial design

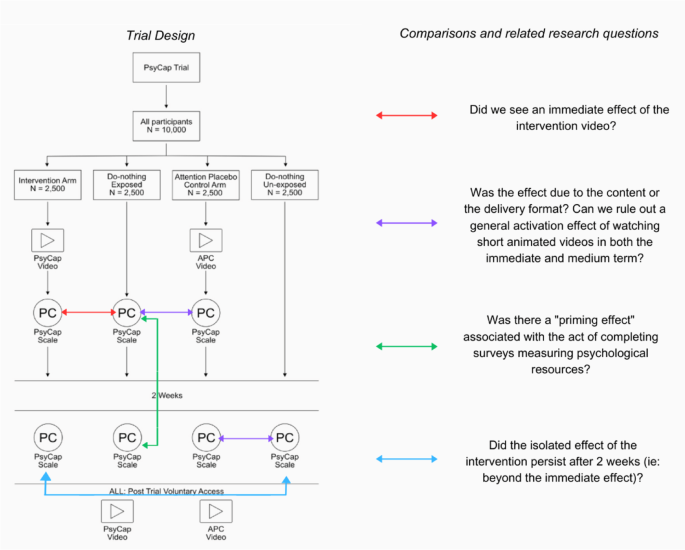

We conducted a parallel-arm, randomized-controlled trial examining the effect of short, animated storytelling video content on PsyCap, gratitude and happiness. We engaged Prolific Academic, an online, academic research platform, aiming to recruit 10,000 US participants (aged 18–59) into four groups: (1) Intervention (PsyCap-SAS), (2) Do-nothing Exposed, (3) Attention Placebo Control (APC-SAS), and (4) Do-nothing Unexposed. Each group’s outcomes were measured at two time points, two weeks apart.

At Timepoint 1, the Intervention Arm watched a PsyCap-SAS video designed to promote PsyCap and, immediately thereafter, completed three surveys: a 12-item validated PsyCap scale (the CPC-12R)3, a 6-item validated gratitude scale (the GQ-6)21 and a single-item validated happiness scale22. The Do-nothing Exposed Control Arm watched no video content at Timepoint 1, but completed all three surveys. The Attention Placebo Control (APC-SAS) Arm viewed a short, animated, storytelling APC video, which we expected to be unrelated to the outcomes measured in this trial. (The APC-SAS was an animated story video aimed at promoting healthy eating.) Thereafter, participants completed all three surveys. The Un-exposed Control Arm watched neither video, nor completed surveys at Timepoint 1.

Two weeks later, all four arms completed the three surveys. For the first three arms, this was a repeat exposure to the surveys and for the fourth arm, this was their first time completing the surveys. After completion of the trial, all four arms were offered post-trial access to both the PsyCap-SAS and APC-SAS videos.

Figure 1 illustrates the planned trial design, and the research questions to be explored.

This trial was conducted entirely online. Participants were recruited through the Prolific Academic ProA (https://www.prolific.co) academic research platform. The study was also hosted online, via the secure, online experiment builder platform, Gorilla, where participants were randomized, took part in the intervention, and responded to the survey questions.

Participants and eligibility criteria

Eligible participants were English-speaking adults, between the ages of 18 and 59 years, living in the US. ProA recruited participants from their registered research participant pool.

Informed consent

The ProA platform obtained informed consent from all participants prior to their enrollment into the study. This process involved thoroughly informing all participants about the purpose, potential benefits, and potential risks of participating in the study. Contact information for both the principal investigator and the Stanford Ethics Review Board was provided to participants. Individuals registered on ProA must agree to the terms and conditions for collection and use of participant data, as well as the privacy policy of ProA, upon registration.

InterventionIntervention and attention placebo control video descriptions

The PsyCap-SAS intervention used in this trial was a short, 2D animated storytelling video designed to boost positive psychological capital, abbreviated here as PsyCap. The video was developed by a group of educators, psychiatrists, psychologists, communication specialists and global mental health advocates from the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC), Stanford Medicine, the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley Medical School, UNICEF and the WHO. The approximately 3.5 min animated video tells the story of Ario, a fantasy creature living in the clouds, who has lost the ability to fly in the post-pandemic environment, which has been described as volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous1. Despite this, Ario is determined to help young people around the world who are struggling to cope after the COVID-19 pandemic. With the help of his friends, Ario reconnects with the four “HERO” elements of his own psychological capital (hope, efficacy, resilience and optimism) and he remembers how to fly. The main character embodies all four PsyCap elements equally and they allow him to travel the world, lifting others up along his journey. Social Cognitive Theory emphasizes the importance of observing and modelling the behaviors, attitudes, and emotional reactions of others, with the result being that the viewer adopts similar behaviors, attitudes and emotions23. The PsyCap-SAS intervention video was developed during the COVID-19 pandemic as an adaptation of the WHO’s children’s book, My Hero is You24.

The attention placebo control (APC) in this trial was also a short, animated storytelling (SAS) video, developed by the same team at Stanford Medicine, in collaboration with faculty at the Heidelberg Institute of Global Health and the Freiberg University Clinic Cardiology Department, in Germany. The APC-SAS video was a short, 2D animated video, focused on boosting knowledge about the sodium content in various foods. The video was created to promote awareness and behavioral intention to reduce dietary sodium, thereby supporting heart health. The APC-SAS video portrays a humorous, animated story in which the main character is a heart, who wakes his owner up complaining that he is under too much pressure, and on the verge of quitting. The owner, shocked and confused, listens as his heart admonishes him for his dietary sodium intake, and then proceeds to educate him about ways in which he can consume a lower sodium diet. The video ends with the owner promising to reduce his dietary sodium if the heart promises not to quit on him. The heart agrees, goes back to work, and the man wakes up to cook a healthy, low-sodium breakfast, telling his wife that he had “the craziest dream”.

Once considered only a young children’s medium, animation has grown in popularity among adolescents and even adults. Recent decades have seen the success of several animated shows aimed primarily at adolescents and adults, (for example, the popular comedy series The Simpsons, Rick and Morty, and Central Park). Today, animation is a driving force in adolescent and adult media25. Since co-viewing of children’s media has been shown to support both children’s and parents’ emotional wellbeing26, this study will explore whether an intervention designed to boost hope and other positive psychological characteristics in children, can measurably boost these characteristics in adults as well. The intervention video contains no dialogue. Instead, it is propelled by an inspiring, original soundtrack, also designed to promote hopefulness. The APC-SAS is a 2D animated video of a similar length, originally created for adults, and focused on educating viewers about how to reduce sodium in their diets. Links to both videos can be found in the Multimedia Appendix. Figure 2 features key screenshots from the intervention and APC videos.

Screenshots from the short, animated storytelling PsyCap Intervention and Attention Placebo Control videos.

MeasuresControl groups and comparators

At Timepoint 1, PsyCap, GQ-6 and happiness scale scores were compared between the Intervention Arm and the Do-Nothing Exposed Control Arm, “Exposed” because they were exposed to the outcome measures at Timepoint 1. Assuming successful randomization, the only difference between these two arms at the first data collection timepoint, was that the Intervention Arm had viewed the Intervention video and the Do-Nothing Exposed Control Arm had not. In order to isolate the effect of the PsyCap messaging specifically, and to exclude the possibility of a general effect on our outcomes from SAS video-viewing, the scores of Arm 1 and Arm 2 were also compared with the scores of Arm 3, the Attention Placebo Control Arm. This third arm watched a short, animated storytelling video about dietary sodium. In this first study phase, the fourth study arm remained un-exposed to both the video content and the surveys. Two weeks later, all four study arms completed the CPC-12R, the GQ-6 as well as a single-item validated happiness scale. The choice of a two-week follow-up for the medium-term data collection point was based on: a) the minimal nature of the intervention—participants received only a single exposure to a short duration (~ 3 min) “micro” intervention and b) published recommendations for conducting online experiments27. Comparisons between the Intervention Arm and the Do-Nothing Un-Exposed Control arm at 2-weeks allowed us to measure the effect of the PsyCap video after two weeks on these psychological constructs. Comparisons between Arm 3 and Arm 4 allowed us to determine whether any observed effect related to viewing of the APC-SAS video persisted after two weeks and comparisons between Arm 2 and Arm 4 allowed us to measure the potential effect of merely exposing participants to these psychological scales, on their PsyCap, gratitude and happiness scores, 2 weeks later.

Primary outcome

For our primary outcome, we measured the immediate effect of the PsyCap-SAS Intervention video on psychological capital (PsyCap).

Secondary outcomes

Our secondary outcomes include quantifying:

(a)

the medium-term effect of the PsyCap-SAS intervention video on PsyCap after two weeks

(b)

the effect of the PsyCap-SAS intervention video on gratitude and happiness, both related to the construct of positive psychological capital

(c)

the effect of exposure to PsyCap and related psychological scales on these same outcomes, measured two weeks later.

Sample size

We calculated the sample size needed for comparison of means between selected arms as detailed in the trial design. This was done independently for the primary and secondary outcomes based on the score of each scale, upon which we selected the most conservative sample size for our study. All the calculations are based on one-tailed comparisons of the mean score with equal variance, equal allocation between arms, a type I error of 0.01 to account for multiple comparisons, and a high power of 95% to detect changes in the mean score.

Recent trends towards increasing social media use and consumption of short video content has shortened consumers’ attention spans28. Content is often posted on social media in real time and social media users around the globe are able to react in seconds. This means that we are increasingly accustomed to consuming information in micro-doses, amplified through the repeat exposure that results from multiple reactions and reposts before moving on to the next sound byte28. As a result of these trends, we assume that short, animated health messages would be most effective if consumed repeatedly over time, with their messages amplified through community engagement. In our study, participants had only one opportunity to engage with the video intervention, before we measured its effect. Thus, we aimed to capture only a very small change in the score of the individual scales, presuming that these small changes could be amplified in the real-world social media environment.

The primary outcome, the PsyCap scale (CPC-12R), consists of 12 items. Participants can score between 12 and 72, but prior research suggests that the mean score is 54.47 (SD = 8.131)3. A recent meta-analysis of PsyCap interventions found the overall effect of the interventions to be significant, but small12. One intervention, described in the literature as an effective “micro-intervention” yielded a 3% increase in PsyCap (an increase of 1.63 points, assuming a mean score of 54.47) however the “micro-intervention” described in that study was more than an hour long10. Given that our intervention is less than 3.5 min long, we would consider an increase of 1 point to be a highly significant effect. The required sample size is calculated as 2087 individuals per arm for this outcome. The secondary outcome, the GQ-6, consists of 6 items on a 7-point Likert scale. Participants can score between 6 and 42, but prior research suggests that the mean score is 34.3 (SD = 8.12)29. We assume that watching the video can move the score up by 1 point, which yields a required sample size of 2081 per arm. The single-item validated happiness scale consists of one question that can be answered by a number from 0 to 10, thus the participants can score between 0 and 10 points. Prior research suggests that the mean score is 6.5 (SD = 2.9)22. Detecting a change of 0.5 points requires a sample size of 1063 per arm.

The largest sample size per arm across the three main outcomes is thus 2087. To account for a potential 20% attrition rate due to the longitudinal design (personal communication with ProA), the sample size for each arm of the study is increased to 2504 participants per arm. For this study, we will recruit 10,000 participants (2500 per arm) which allows us to detect the defined score changes by the intervention with the power approximately 95%.

Assignment of interventions: allocation

The study was hosted on the Gorilla experiment-builder platform.. A random allocation sequence was used to allocate participants 1:1:1:1 to the four trial arms. The randomization algorithm does not allow the investigators to influence the individual trial arm allocations and provides an effective concealment mechanism.

Assignment of interventions: blinding

All study investigators and researchers involved in the data analyses remained blinded to the trial arm allocation for the entire study duration. Unblinding was not needed.

Participant timeline

Over a 4-week period, participants were recruited and enrolled on the ProA platform. The first phase of the trial (involving video viewing and subsequent scale response submission) occurred two weeks before the second phase (follow-up scale response submission). Immediately after the completion of the second phase, all participants were given post-trial access to the SAS video content. Their view times were recorded on Gorilla and used as an indicator of voluntary participant engagement with this type of content. Since the dissemination of SAS interventions relies on spontaneous viewing and sharing, engagement with the content is an important metric.

Strategies to improve adherence to interventions

Participants were informed upon enrolment that they would be paid ($3.50 for 15 min) after completing the entire study. We chose to follow up after two weeks in order to optimize our need to assess the potential transience of our outcomes over time, while minimizing drop-out rates. We also embedded attention-check questions within the surveys to ensure that participants watched the video and were reading the survey questions carefully.

In order to ensure that participants had carefully watched the intervention (or APC) video, they were asked a question related to the content of the video that was straightforward for participants who had watched their assigned video. Participants who had not attended carefully would likely not be able to answer correctly, and these participants were excluded because we considered the intervention (or APC) not to have been delivered.

Throughout the surveys, we also added attention check questions that were unrelated to the PsyCap scales and had an obvious and unmistakable answer, provided the participant read the question. The attentions checks were formatted similarly to the assessment questions, so they were not easily distinguishable if a participant was “clicking through” the survey. A sample attention check question is shown in Appendix Fig. 7. The data of participants who failed two or more attention checks was excluded from the analysis.

Criteria for discontinuing or modifying allocated interventions

We did not discontinue or modify the allocated interventions during the course of the trial. Participants were aware that they could discontinue and withdraw their consent to participate at any time. We did not use incomplete survey data, except at a meta-level where we reported the aggregate number of incomplete surveys. Participants could only complete the surveys once at each time point.

Relevant concomitant care permitted or prohibited during the trial

Concomitant care was neither permitted nor prohibited during this study.

Provisions for post-trial care

The foreseeable risks associated with participating in this study were extremely minimal. Participants had volunteered and consented to participate in this short, animated storytelling trial, and they were able to withdraw at any time. The investigators could also be contacted at any time after the study.

Data collection and managementPlans for assessment and collection of outcomes

Data was collected by the Gorilla experiment-builder platform. Data was submitted directly to Gorilla by individual participants when they chose their responses to the various scale questions hosted on the platform. We completed data collection over a 4-week period.

Plans to promote participant retention and complete follow-up

Participants were automatically timed out of the study if they took longer than 45 min to complete either phase of the survey. This ensured that participants did not burden the system with incomplete surveys. Participants remained anonymous to the investigators throughout the study, so there was no way to follow-up with participants.

Data management

All data collected during this study were stored by Gorilla on its secure, encrypted cloud platform. This platform is hosted on Microsoft Azure, Republic of Ireland. Industry-standard cryptography is used to encrypt the Gorilla database but the research team maintained control over the data, with the ability to access the completely anonymized datasets at any time. For statistical analysis purposes, the data was downloaded and safely stored on a secure computing system maintained by our co-investigators at Heidelberg University, in Germany.

Confidentiality

All participants remained completely anonymous to the investigators in this trial. Investigators did not have access to identifying information associated with the participants’ unique IDs. Participants were informed that, if they chose to contact the investigators with concerns or questions about the study, their names may be revealed to the study team however the team would keep all information and correspondence confidential.