Search results

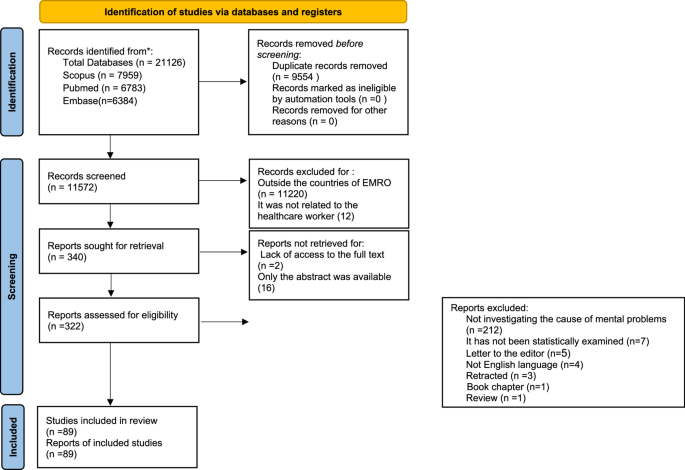

A search conducted across PubMed, Scopus, and Embase databases initially yielded 21,126 records. After removing 9,554 duplicate entries, 11,572 studies remained for screening. Following title and abstract screening, records were excluded due to being outside EMRO countries (n = 11,220), not related to HCWs (n = 12), lack of access to the full text (n = 2), and only having an abstract available (n = 16). Subsequently, a total of 322 reports were assessed for eligibility. Of these, 212 studies did not explicitly address the reasons or contributing factors that led to increased mental health problems among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Instead, most reported on the extent of depression, anxiety, and other issues measured with validated questionnaires, while focusing on the challenges faced by HCWs. Ultimately, 89 studies were included in the review because they met the inclusion criteria and were selected for data extraction. Following this, essential information was collected through a detailed review of the abstracts and full texts. The Table 3 showed extraction details of the surveys. Search strategy flowchart and study selection is presented in Fig. 1.

Table 3 Characteristics of selected studies evaluating factors associated with mental health symptoms among HCWs in EMRO countriesFig. 1

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases and registers only

Quality assessment

All included studies were assessed using the modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS). The scores of the studies ranged from 6 to 9, with an average score of 7.9. The high scores observed in most studies were primarily due to the use of validated measurement tools and appropriate statistical analyses. Notably, the majority of studies scored highly in the domains of comparability of study groups and outcome assessment. However, lower scores were typically attributed to deficiencies in the selection of the study sample, particularly in the lack of justification for sample size or power calculations. Additionally, several studies did not adequately address the potential bias introduced by non-respondents or excluded participants. Despite these limitations, few studies were classified as having only moderate quality.

Studies characterizations

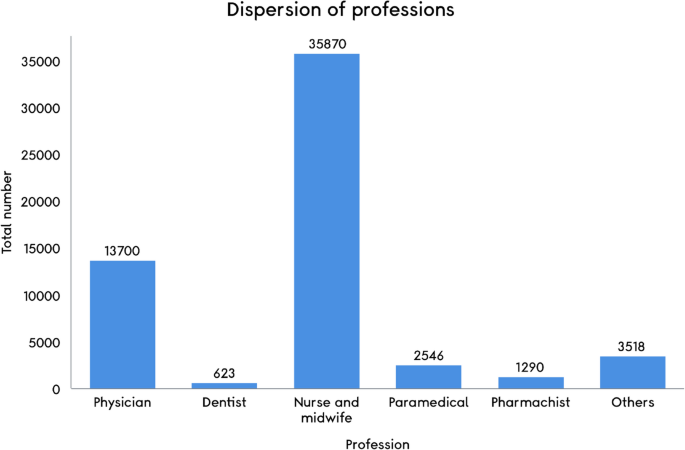

All the 89 references, were done in different regions including Bahrain, Egypt, Emirates, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Morocco, Oman, Pakistan, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Tunisia and Yemen. These collected surveys investigated a total of 62,454 HCWs with different specializations including physicians, nurses, laboratory technicians, midwives, pharmacists, dentists, and other occupations (Fig. 2). The majority of the population analyzed in these articles were physicians and nurses.

Distribution of professions included in the selected EMRO studies. This figure illustrates the distribution of different healthcare professions (e.g., doctors, nurses, etc.) represented in the studies selected from the EMRO region. The data is derived from 79 articles, with 10 excluded. This exclusion is due to the unavailability of data in these 10 articles or the inclusion of mixed data from multiple professions that cannot be separated for accurate figure calculation (for more details see supplemental file 1). Professions not specifically categorized (e.g., administration workers, technicians, security staff) are grouped as “Other professions.” Understanding the diversity of healthcare roles included in the studies is crucial, as it highlights the range of individuals affected by mental health challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic in the region. The predominance of doctors and nurses in the included studies reflects their direct and prolonged patient care roles, which inherently increase their exposure to COVID-19 patients and associated stressors. As frontline workers, they experienced heightened risks of infection and psychological challenges due to the several factors including extended working hours, insufficient personal protective equipment (PPE), and frequent exposure to suffering and death and etc. Recognizing this distribution highlights the need to focus interventions on the most affected groups, while ensuring inclusivity for less-represented professions who may face unique challenges

Medical profession and risk factors associated with mental health symptoms

We examined 89 studies that involved 62,454 HCWs, with nurses and physicians making up the majority of the participants. The distribution of professions among HCWs deployed in the EMRO region is shown in Fig. 2. Additionally, according to the included studies the most common mental health symptoms among healthcare workers in the EMRO region were anxiety (range: 3.4–89.7%), depression (range: 12.4–98%), insomnia (range: 24.5–68.8%), and stress (range: 5.2–95.7%). However, the inherent heterogeneity across the included studies should be considered as a key limitation. While all studies reported the prevalence of mental health symptoms, many employed different assessment tools and set varying thresholds, even when using the same tests. These inconsistencies in screening and evaluation methods may have influenced the reported ranges and affected the comparability of the findings across studies.

As well, the most important risk factors correlated with these mental health symptoms included being female, younger age, fears of transmitting the virus to others, work-related sleep disturbances, and insufficient protective equipment. All data from 89 studies on the characteristics of healthcare workers impacted by COVID-19 in the EMRO region are comprehensively presented in Table 3 and Supplemental File 1. In this section, we outline the characteristics of the studies, organized by country within the EMRO region.

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia is one of the Western Asian nations heavily impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. On March 3, 2020, the Saudi Ministry of Health reported the country’s first confirmed case of coronavirus [25]. Since that time, several studies have investigated the mental health effects of the COVID-19 crisis on HCWs in Saudi Arabia. As shown in Table 3, the most mental health symptoms among HCWs were anxiety, depression, insomnia and stress. Alenazi et al. conducted a study focusing on assessing anxiety levels among HCWs in Saudi Arabia. Out of 4,920 respondents, 31.5% (n = 1,552) exhibited low anxiety, 36.1% (n = 1,778) experienced moderate anxiety, and 32.3% (n = 1,590) reported high anxiety [26]. In a separate investigation focused on determining the rates of depression, anxiety, and stress among HCWs in Saudi Arabia, findings from a sample of 502 HCWs indicated that 54.69% experienced depression, 60.88% faced anxiety, and 41.92% dealt with stress. Further investigations showed that HCWs with chronic illnesses, nurses, and those from the southern region were at a higher risk of developing depression and stress. Additionally, beyond these mental health challenges brought on by COVID-19, several studies have highlighted the occurrence of PTSD in HCWs [27, 28]. Furthermore, a study by Alabdullatif et al. explored the connection between depression, anxiety, and sleep quality among nurses working in Saudi Arabian hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings revealed that among 187 nurses, 88% suffered from poor sleep quality, 44.4% experienced moderate anxiety, and 44% exhibited mild to moderate depression [29]. The study demonstrated a link between higher levels of anxiety and poorer sleep quality. Good sleep quality is a strong indicator of both positive mental and physical health, whereas poor sleep can exacerbate psychological issues such as insomnia, anxiety, and depression [29]. Conversely, some research suggests that HCWs in Saudi Arabia reported lower rates of depression, anxiety, and insomnia symptoms. A cross-sectional survey involving 720 HCWs in Saudi Arabia, revealed that these symptoms were less prevalent among the participants. This finding suggests that the health care environment and organizational initiatives were effectively managed [30]. Results from other studies conducted in Saudi Arabia are presented in Table 3 and Supplemental File 1.

Some studies in Saudi Arabia have identified female gender as a risk factor for experiencing mental health symptoms [30,31,32]. The study by Almater et al. revealed that mental health symptoms were more prevalent among female ophthalmologists. Their findings indicated that female ophthalmologists were more likely than their male counterparts to experience symptoms of depression, anxiety, and moderate-to-high levels of stress [31]. The research conducted by Alhurishi et al. reveals that female nurses and HCWs on the frontlines of COVID-19 care face a heightened likelihood of experiencing severe mental health challenges, including depression, anxiety, and emotional distress [33]. In the analysis by Moussa et al., female nurses reported higher fear scores compared to their male counterparts. This heightened fear among female nurses could be attributed to their greater exposure to stressful life events, such as household responsibilities and caregiving roles, which are less common among male nurses [34]. Conversely, the analysis conducted by Rasheed et al. revealed differing findings, indicating significant gender disparities in stress levels during the COVID-19 pandemic. Interestingly, female nursing professionals reported experiencing less stress than their male counterparts [35].

In addition to being female, younger age has been identified in several studies as a potential risk factor for developing mental health symptoms [32, 36, 37]. For instance, in the study by Alamri et al., anxiety levels were significantly higher among younger staff compared to their older counterpart [32]. This may be attributed to the relative inexperience of the younger medical staff, who have less hands-on experience in the field and are less directly involved in managing suspected or confirmed cases. As a result, they may be more prone to mental distress when faced with unexpected public health crises [38]. Additionally, various risk factors have been identified, including concerns about transmitting the infection to family members, having pre-existing health conditions, and working on the frontlines [32, 33, 39].

Iran

The first confirmed case of COVID-19 in Iran was officially recorded in Qom on February 19, 2020. The virus spread more swiftly than anticipated, and by March 5, 2020, the entire nation was affected [40]. In Iran, the escalating number of confirmed cases, combined with a shortage of personal protective equipment, heavy workloads, extensive media coverage, insufficient support, and the absence of targeted treatments, contributed to heightened psychological stress among HCWs [40]. Consequently, numerous investigations have been accomplished to assess the psychological impact of COVID-19 on HCWs in Iran.

Kamali et al. conducted a cross-sectional study to evaluate anxiety, depression, and stress levels among HCWs in Iran [41]. Out of 1,343 participants, 45.8% reported experiencing moderate physical anxiety symptoms, while 73.0% had moderate psychological anxiety. Additionally, 35.1% of the HCWs were found to have depression, and 27.8% reported stress. The study also identified significant associations between depression and age, as well as between stress and gender [41]. Sabbaghi et al. conducted a cross-sectional study involving 544 pre-hospital emergency medicine personnel, revealing a 36.2% prevalence of depression, 36.7% anxiety and 31.0% stres. Their analysis showed significant correlations between depression and stress with employment type. Additionally, stress was significantly linked to working fewer than 35 h per week and living apart from family (p 42]. In addition to these mental health issues, several analyses have reported the presence of PTSD among Iranian HCWs, similar to findings in Saudi Arabia [43,44,45].

As nurses serve as fundamental components of healthcare systems, their role during the COVID-19 pandemic has been pivotal in driving health interventions and tackling various challenges. Being at the forefront, they are exposed to numerous hardships, such as increased infection risks, inadequate protective gear, and shortages of critical medications. These conditions can significantly elevate their susceptibility to insomnia, frustration, fear, stress, anxiety, and depression [46, 47]. As a result, several studies have been performed to examining the risk factors for mental health problems associated with COVID-19 among nurses. In the study by Behnoush et al., which assessed anxiety and depression among nurses diagnosed with COVID-19, 72.8% of the 158 participants reported experiencing anxiety, while 42.4% reported depression. Moreover, the study highlighted that the primary source of these psychological challenges stemmed from concerns about transmitting the virus to family members [48]. In 2020–2021, a cross-sectional study was carried out to evaluate depression, anxiety, and stress levels among Iranian nurses caring for COVID-19 patients. The average scores and prevalence rates for depression, anxiety, and stress were 13.56 ± 5.37 (74.1%), 13.21 ± 4.90 (89.7%), and 15.13 ± 4.76 (54.9%), respectively [49]. There were significant associations between the mean scores for depression, anxiety, and stress and the participants’ employment status. Additionally, anxiety scores were significantly related to educational level, employment status, and work shift (p 49]. A larger study with a sample size of 1,135 aimed to evaluate the prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress among Iranian nurses during the pandemic and investigate potential contributing factors for each mental health issue [50]. The findings revealed that the rates of stress, anxiety, and depression among nurses were 75.6%, 79.2%, and 59.1%, respectively. The study identified several factors associated with increased stress, such as being female, younger age, and high work demands. Higher anxiety levels were linked to being female, younger, and having lower educational attainment. Additionally, factors like lower education levels, extended working hours, and working in intensive care units were significantly connected with an increased risk of depressive symptoms among nurses [50]. Similarly, most studies in Iran have identified being female and of younger age as significant risk factors for mental health issues [41, 50,51,52]. These observations can be attributed to the fact that female students often experience less social support, leading to a diminished sense of cohesion [44]. Besides, the higher prevalence of mental disorders among female students compared to males may be influenced by biological factors, gender roles, environmental stressors, low satisfaction levels, and limited social participation of women in society. Additionally, differences in stress management strategies between genders also play a role [44]. Remarkably, in a study by Kolivand et al., it was observed that even two years after the COVID-19 outbreak, HCWs continued to experience significant levels of depression, anxiety, stress, and notable psychological distress [53]. Additionally, being female was correlated with higher probabilities of experiencing depression, anxiety, and stress [53]. The findings from additional studies conducted in Iran are summarized in Table 3 and Supplemental File 1.

Pakistan

On February 26, 2020, Pakistan identified its initial coronavirus case [54]. The onset of this pandemic has significantly burdened HCWs in a country with limited resources, both physically and psychologically. In Pakistan, HCWs have endured heightened psychological stress due to the several factors including, shortage of personal protective equipment, disruptions in sleep, fatigue from staff shortages, and reduced family interactions leading to diminished social support [55, 56]. Such stressors can lead to a variety of mental health challenges among these workers. Therefore, it’s crucial to gather epidemiological data on the mental health impacts of COVID-19 on HCWs.

Research has identified multiple factors linked to mental health challenges among HCWs in Pakistan. One notable factor is being female, a pattern also observed in countries like Iran and Saudi Arabia. For instance, a study by Sarwar et al. found that female nurses with average professional roles experienced significant symptoms of depression, anxiety, emotional distress, and insomnia [55]. Idrees et al. also noted that women experience elevated levels of psychological distress compared to men [57]. Being a woman and belonging to a younger age group have been identified as risk factors for mental health issues among healthcare workers in Pakistan [58, 59]. Haroon et al. carried out a cross-sectional study in an emergency department utilizing the generalized anxiety scale (GAD-7). Their findings indicated that 50.5% of the 107 HCWs experienced anxiety. Additionally, the study identified key stressors, including the apprehension of transmitting infection to family members, insufficient social support during the workers’ own illnesses, younger and inexperienced staff, and concerns about poor work performance [58]. Nonetheless, some studies present contrasting findings. For example, Tahir et al. reported in their survey of 504 medical students and physicians that the rates of anxiety and depression were found to be 3.4% and 15.1%, respectively. They suggested that these lower levels of anxiety and depression were due to the high awareness of COVID-19 among doctors and medical students [59]. Additionally, other studies have reported that fear of COVID-19 is significantly linked to workplace phobia, which could potentially impair doctors’ performance [60]. The results from supplementary studies carried out in Pakistan are presented in Table 3 and Supplemental File 1.

Egypt

Egypt confirmed its first COVID-19 case on February 14, 2020 [61]. Egypt, much like Saudi Arabia, has been heavily impacted both in terms of human suffering and financial strain during the pandemic. Residing in regions severely affected by COVID-19 has been linked to increased psychological distress [62]. As a result, various studies have been carried out to evaluate the mental health challenges experienced by frontline HCWs in Egypt.

Abdelghani et al. carried out a cross-sectional study involving 426 Egyptian physicians who worked during the COVID-19 pandemic to investigate coronaphobia, a newly recognized phenomenon, and its associated factors among HCWs [63]. The study found that 28% of the participants experienced moderate to severe anxiety, while 30% reported similar levels of depression. Physicians with elevated coronaphobia were more often female, non-smokers, had thoughts of death or self-harm, received inadequate training, were dissatisfied with their PPE, and had colleagues infected with COVID-19. A strong correlation was observed between coronaphobia and anxiety (P P 63]. In an another study involving 237 physicians, findings indicated that 78.9% experienced symptoms of anxiety and 43.8% suffered from depression [64]. Among the respondents, 85% had children, which was linked to a markedly higher risk of anxiety. The study identified several key factors contributing to the anxiety and depressive symptoms. The identified factors included inadequate sleep quality, holding the position of a resident physician, interruptions to social interactions, and facing stigma associated with COVID-19 [64]. Similar to other nations within the EMRO region, gender has been identified as a significant determinant of mental health challenges among HCWs. Research by Elkholy et al. highlighted that women face a heightened likelihood of experiencing severe anxiety, depression, and stress compared to their male counterparts [65]. As well, Hegazy et al.‘s research revealed that female HCWs experienced higher levels of depression, anxiety, and emotional distress compared to their male counterparts [66]. In Egypt, younger age has been recognized as a risk factor. Elgohary et al. found that being younger, having fewer hours of sleep, being female, having a history of psychiatric conditions, and experiencing fears related to COVID-19 (such as contracting the virus, loved ones being infected, or concerns about death) were significant indicators for both the likelihood and severity of major depressive disorder [67]. Elghazally et al., in a separate study, highlighted that depression symptoms were prevalent among HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly among younger individuals and frontline medical professionals [68].

These significant mental health challenges faced by HCWs and the general population in Egypt during the COVID-19 pandemic prompted a response from the Egyptian ministry of health. On March 31, 2020, they launched two hotlines dedicated to providing psychological support [68]. This initiative not only involved the deployment of mental health professionals trained in remote assistance but also saw the expansion of services through the integration of psychiatrists in quarantine hospitals. These efforts were aimed at delivering specialized mental health care to both COVID-19 patients and HCWs, as well as supporting individuals with pre-existing mental health conditions [68].

Emirates and oman

The initial instance of the SARS-CoV-2 virus was identified in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) on January 29, 2020 [69]. By December 2023, the UAE had reported 1.6 million confirmed cases and 2,349 fatalities [70]. Throughout the pandemic, HCWs have experienced significant psychological effects, including anxiety, psychological distress, depression, and burnout [70,71,72]. A study by Ajab et al. sought to investigate both the accessibility of PPE and the prevalence of anxiety, depression, and burnout among HCWs in the UAE [71]. Out of 1,290 HCWs surveyed, 80% reported that PPE was sufficiently available. However, a significant portion of the participants experienced psychological and physical challenges: 26.3% reported anxiety, 28.1% faced depression, and over half felt physically exhausted (52.2%) and experienced musculoskeletal pain or discomfort (54.2%). Additionally, 52.8% of HCWs had moderate-to-high levels of burnout [71]. Saddik et al.‘s research highlights various factors that contribute to mental health challenges among healthcare workers [72]. The study revealed that women experienced greater levels of anxiety related to COVID-19. Additionally, a higher proportion of female healthcare workers and frontline staff faced moderate to severe anxiety, which tended to lessen with age. Concerns about transmitting the virus to family members and the possibility of isolation were identified as separate risk factors for significant psychological distress. Female gender, stigmatization, social withdrawal by loved ones, and the fear of contracting COVID-19 were all recognized as independent risk factors for moderate to severe generalized anxiety disorder [72]. Additionally, AlGhufli et al. found that frontline healthcare workers were more vulnerable to experiencing burnout symptoms [73]. Moreover, factors such as being younger, unmarried, a nurse without children, and having changed living arrangements during the crisis were connected with an increased risk of developing burnout symptoms. Adjusted linear regression analysis revealed that age was the primary independent factor influencing anxiety and stress subscales, although it did not affect insomnia levels. Additionally, concerns about the well-being of family and loved ones were found to independently contribute to higher levels of depression and anxiety [73].

Oman’s initial COVID-19 cases were identified on February 24, involving two Omani citizens who had traveled to Iran [74]. Similar to other affected nations, HCWs in Oman encountered a range of mental health challenges, including insomnia, depression, anxiety, and stress [75,76,77]. Khamis et al. carried out a study assessing the mental health of 402 HCWs, comprising 28.4% physicians and 71.6% nurses. Among the participants, 231 (57.5%) were Omani and 171 (42.5%) were non-Omani. The study revealed that approximately 27.9% of the individuals experienced moderate to severe levels of anxiety [75]. Additionally, various risk factors, such as being female and younger, have been identified as being linked to mental health issues among healthcare workers in Oman [76, 77]. The findings from additional studies conducted in UAE and Oman are summarized in Table 3 and Supplemental File 1.

Altogether, the examination of mental health issues among HCWs across various countries in the EMRO region during the COVID-19 pandemic reveals a troubling prevalence of psychological disorders. Significant rates of anxiety, depression, and stress among HCWs have been consistently reported in countries such as Saudi Arabia, Iran, Pakistan, Egypt, and the UAE. These mental health challenges are exacerbated by factors such as being female, younger age, high work demands, inadequate protective equipment, insufficient social support, and the fear of transmitting the virus to loved ones. These findings can be attributed to several factors commonly observed in the EMRO. One such factor is that many countries in the EMRO are impacted by armed conflict. Whether ongoing or sudden, conflict severely disrupts healthcare infrastructure and facilities, leads to shortages in both health resources and personnel, causes large-scale population displacement, and restricts access to essential healthcare services [78]. Another contributing factor could be the cultural characteristics of the region which impacts femlas in this region. Women, in particular, are more susceptible to mental health disorders due to a range of influences, including socio-cultural pressures, violence, stress, poverty, conflict, migration, and social inequality [79]. For instance, in Lebanon, female nurses have pointed out several challenges, including insufficient support from supervisors, limited access to training and professional development opportunities, and discrimination in recruitment and promotion processes [80]. Overall, The EMRO is a densely populated region characterized by weak healthcare systems, which are marked by shortages of medical resources and equipment, as well as a lack of operative prevention plans. These factors significantly contribute to the augmented workload and psychological stress experienced by healthcare workers [17]. Additionally, it is important to note that the EMR is a highly heterogeneous region with vast economic, social, cultural, and health disparities among its countries.

Given the widespread and severe impact of these mental health issues, it is imperative to prioritize targeted interventions to support HCWs. Addressing these concerns requires a multifaceted approach, including the implementation of robust psychological support systems, improved training, and better access to mental health resources. Initiatives such as the launch of hotlines and the deployment of mental health professionals, as seen in Egypt, represent positive steps forward. By addressing these mental health challenges, we not only support the well-being of HCWs but also enhance their capacity to deliver effective patient care. Ensuring that HCWs have access to comprehensive mental health support is crucial for maintaining a resilient HCWs capable of navigating future crises effectively. Detailed findings from additional studies conducted in other EMRO countries are thoroughly present in Table 3.