6 min read

In 2024, Jonathan Haidt published his bestseller The Anxious Generation and spoke with Oprah for “The Life You Want: Teen Mental Health” about the mounting global teen mental health crisis and the “great rewriting” of childhood from play-based to phone-based, fueled by smartphones and social media. Since then, his message about how technology affects kids’ well-being—which Oprah has called “one of the most pressing issues of our time”—has reached millions. In his two appearances on The Oprah Podcast, he spoke to parents who had managed to raise (well-adjusted, highly social) children without smartphones and to those dealing with the cognitive and emotional consequences of their teens’ dependence on highly addictive technology. Haidt has remained steadfast in his advice that parents should not let their kids get a smartphone until at least age 14 and should keep them off social media until at least 16, ideas that are now codified in law in Australia with its recent age restrictions on sites like TikTok, X, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, Snapchat, and Threads.

Even with his research gaining real traction, Haidt’s conversations keep circling back to one familiar impasse: Parents want to delay smartphone use, kids insist that “everyone else has one”—and, often, peer pressure wins out. Rather than “raining down” on children from above, Haidt realized he needed to meet young people on their level and tell them a story that would empower them to choose a real childhood over a virtual one, on their own terms.

You only get one childhood, and for most kids, Meta owns it.

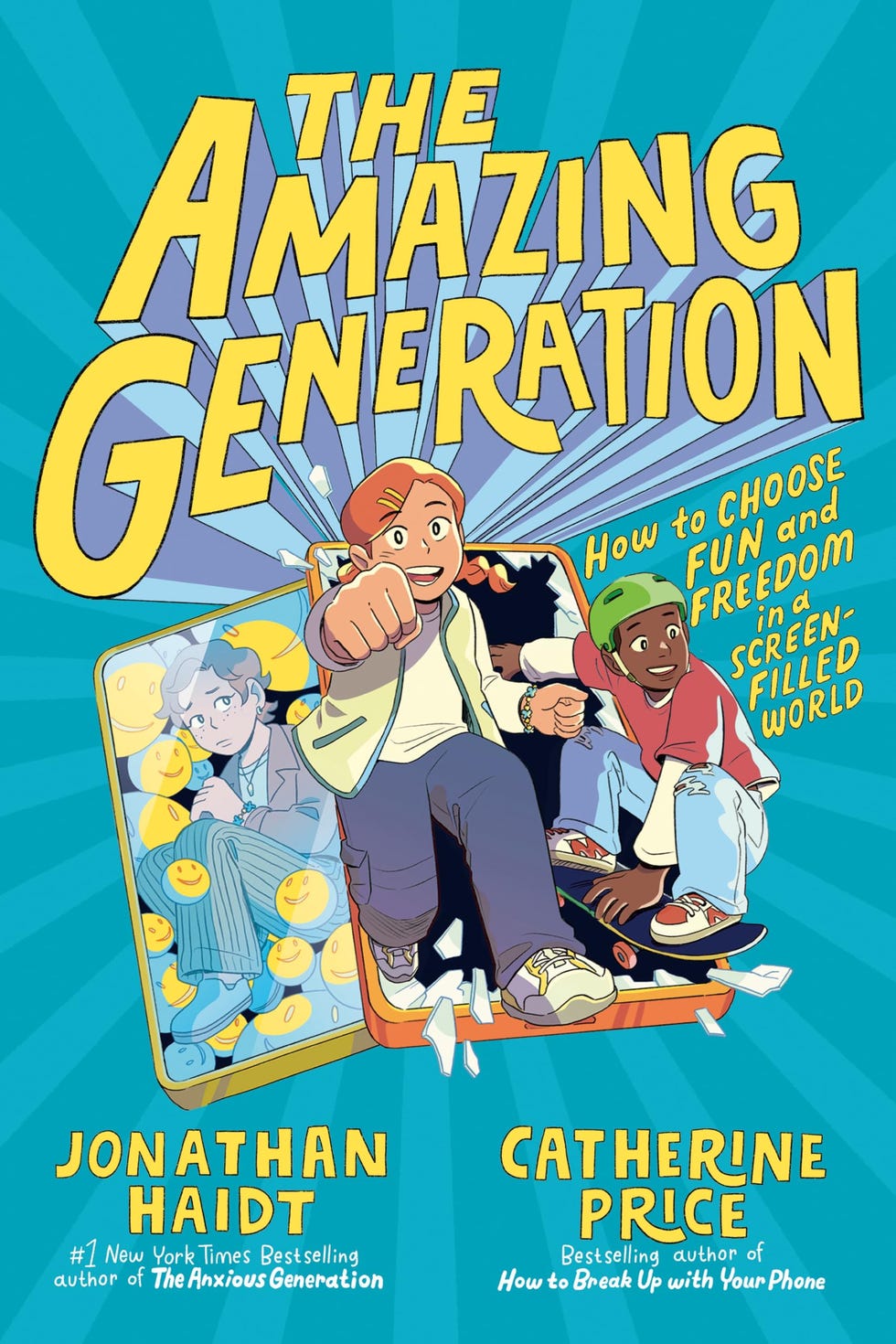

He teamed up with Catherine Price, the author of How to Break Up with Your Phone—who had joined Oprah for a separate “The Life You Want” class on cultivating more joy—to write The Amazing Generation, an illustrated call to action aimed at 9- to 12-year-olds but accessible to pretty much anyone who wants to cut down on their screen time. Though neither had previously written a children’s book, both had lived experience as parents and research expertise on effective persuasion strategies that made them uniquely well-suited for the job. To celebrate the publication of The Amazing Generation, our editor at large, Gayle King, is hosting a special event with both authors, as well as special guests, including comedian Amy Schumer. Ahead of that conversation, Haidt and Price shared some research-backed, parent-approved strategies they picked up while writing the book that can help any parent navigate “the phone conversation” with clear boundaries, fewer power struggles, and a plan you can actually stick to.

Intervene Early

While so-called “screenagers” are often the poster children for tech debates, Price and Haidt were intentional in their decision to write The Amazing Generation for kids who hadn’t yet hit adolescence. “The most fateful decision is when the kid gets a phone,” Haidt explains. By age 11 or 12, the majority of kids already have a smartphone, and “for a large percentage, it’s going to move to the center of their lives and stay there forever.” Practically, it’s much easier to prevent the phone from becoming a child’s gravitational center than to wrestle it away once it’s already embedded in their routine. Scientifically, most of the cognitive damage from smartphone and social media use occurs during early childhood and puberty, so delaying access helps future-proof the brain by protecting the critical development of attention, emotional regulation, and social processing.

The authors conducted focus groups and determined that kids ages 9 to 12 would be most receptive to the book’s message, a finding that Price saw in action when she presented the ideas to fourth and fifth graders at her daughters’ school. She didn’t get a single eye roll, and the students went over the allotted time asking questions, sharing their own stories, and talking about which flip phones they wanted to get in place of an iPhone. “If kids hate one thing, it’s being taken advantage of—they get very indignant,” Price explains, noting how enraged the students became when she explained how tech companies profit off shrinking their years of play and exploration to the dimensions of a touchscreen.

“You only get one childhood, and for most kids, Meta owns it,” Haidt adds.

Nail the Tone

“The way to get kids buy-in is not to lecture at them,” Price says. “Any parent who’s had a fight with their kid about screen time knows that that is not the winning approach.” Before becoming a science journalist, Price had taught and tutored kids in middle school through high school and says she still has “the sense of humor of a middle school boy.” Bringing humor and connection into this serious discussion isn’t just a garnish; it’s a persuasive strategy. Through teaching and through the research she did for The Power of Fun, her 2021 book on replacing the artificial “rewards” of technology with real-world happiness, she understands that laughter and fun are critical to learning.

While there is no shortage of alarming research on the impact of tech on developing brains, Haidt knows from his research on morality that “you don’t persuade people by giving them reasons and evidence; you persuade them by speaking to the heart and giving them an intuitive sense of what you’re saying and then backing it up with evidence.” In practice, that can mean starting with a gut-level hook—“I’ve had nights where I’m tired and still can’t stop scrolling; have you?”—before presenting your evidence. If you don’t have that connection in the first place, “all the evidence in the world isn’t going to change their minds.”

The Amazing Generation is designed to foster connection between parents and children with prompts like the one encouraging kids to ask the adults in their lives over a certain age to imitate the sound of a dial-up modem—and brace themselves. Price has already heard accounts from friends about the hilarity that ensues. “I think the playful attitude that we have in the book really equalizes the playing field between adults and kids and encourages these conversations as equals, rather than this top-down lecturing, confrontational approach,” she says. Even when talking about serious topics—or especially when talking about serious topics—“the more you can laugh together and the more you have fun together, the more open people are to hearing the message.”

Be the Guinea Pig

In The Anxious Generation, Haidt “deliberately chose” not to ask parents to interrogate their own tech habits, in part “to keep the focus on kids and to not criticize parents and parenting,” but also because, as a social psychologist, he understands that middle schoolers are much more influenced by their peers’ behavior than by adults’. “Of course, they’re going to say, But Mom, you’re always on your phone,” he acknowledges, but that’s because they’re “really good lawyers” attuned to the ways that their parents’ hypocrisy might undermine the boundaries they’re trying to set, not because they plan to mimic Mom’s phone-free lifestyle if only she adopts it first.

Still, there is a power in parents being open about their own struggles with technology and in asking for advice from their own children. Price suggests that a great way to initiate a conversation around screen time that doesn’t feel adversarial is to say, “I’m actually interested in changing some of my own habits too—is there anything you want to try together?” Approached this way, discussions about devices and boundaries shift from parents imposing something to families building something together, giving kids a sense of agency while easing parents out of the role of constant enforcer. “I actually think it really can be a good way to help your kids in kind of an indirect way,” Price adds, “because they like feeling like they’ve got some kind of input on their parents’ behaviors.”

This isn’t a strategic bluff to get kids on board. It’s an honest admission that the device struggle isn’t just a teen problem. Price has heard from kids for years about how ignored and hurt they feel when their parents are on their phones while they’re together. “For all of us, it’s gotten out of control,” she says, “and our kids could help us.”

While dialing back screen time can strengthen your relationship with your kids and make healthier tech norms feel possible, it’s not just good parenting. Haidt and Price are focused on children because screens are threatening to rob them of things they can’t get back: childhood itself and developmental foundations that shape mental health for years to come. But the losses don’t end with childhood, and kids aren’t the only ones who deserve to be indignant about the real-world experiences we are missing out on in our increasingly digitized existence. As Price points out, “We adults deserve to have good lives too.”

The Amazing Generation: Your Guide to Fun and Freedom in a Screen-Filled World, by Jonathan Haidt and Catherine Price

Shop the Oprah Daily “The Life You Want” Collection

Shop the Oprah Daily “The Life You Want” Collection Oprah’s “The Life You Want” Planner

Oprah’s “The Life You Want” Planner Oprah’s “The Life You Want” Love and Happiness Journal

Oprah’s “The Life You Want” Love and Happiness Journal Oprah’s “The Life You Want” Becoming Unstuck Journal

Oprah’s “The Life You Want” Becoming Unstuck Journal Oprah’s “The Life You Want” Finding Your Purpose Journal

Oprah’s “The Life You Want” Finding Your Purpose Journal Oprah’s “The Life You Want” Book Lover’s Journal

Oprah’s “The Life You Want” Book Lover’s Journal

Now 40% Off

Oprah’s “The Life You Want” Daily Inspiration Cards

Oprah’s “The Life You Want” Daily Inspiration Cards Oprah’s “The Life You Want” 100 Questions Everyone Should Ask Conversation Cards

Oprah’s “The Life You Want” 100 Questions Everyone Should Ask Conversation Cards

Charley Burlock is the Books Editor at Oprah Daily where she writes, edits, and assigns stories on all things literary. She holds an MFA in creative nonfiction from NYU, where she also taught undergraduate creative writing. Her work has been featured in the Atlantic, the Los Angeles Review of Books, Hyperallergic, the Apple News Today podcast, and elsewhere. You can read her writing at charleyburlock.com.