It was Easter Sunday 2023, and Shane was supposed to be at his dad’s house in Westchester, New York. The family would sit down to eat at 1 p.m. — the exact same time as first pitch in a low-stakes, early-season game between the New York Mets and the Arizona Diamondbacks.

And so, instead of celebrating with his family, Shane was at Citi Field, alone in 45-degree weather, compulsively watching a team that once brought him so much joy. He had $25,000 on the game.

“I don’t even want to bet, but I can’t not do it,” he told CNN Sports. “And not only can I not do it, but also, I get in this weird state of mind at that point where, if I have big money on the game, I have to be there.”

Eighteen months prior, Shane had never gambled a penny.

“I wouldn’t have known how to find a bookie, even if I knew what a bookie was,” he said.

Then, in 2022, New York legalized online and mobile sports betting and suddenly, rabid fans like Shane were subject to rampant advertising and alluring promotions. The Mets were already a major part of his life, and he was watching most, if not every, game in some capacity. Betting on his favorite team – at first, only them and only to win – seemed like an opportunity to amplify the experience. And maybe make a couple bucks.

“It was a way to feel even closer to the Mets than before,” Shane said. “I don’t know if I really even fully realized that it could be an addiction.”

He stayed at that chilly Easter game until the sixth inning. With the Mets firmly in the lead, he got in the car he rented expressly to stress his wager in person and drove to his dad’s house. He won that bet, but arriving late, windswept, and driving an unfamiliar car piqued his dad’s concern. To every inquiry, Shane lied.

“You’re becoming a different person in front of people, and they don’t even realize it,” he said.

A month later, he sought treatment for gambling addiction, embarking on a precarious sobriety from sports gambling that has changed his relationship to his friends, family, and fandom.

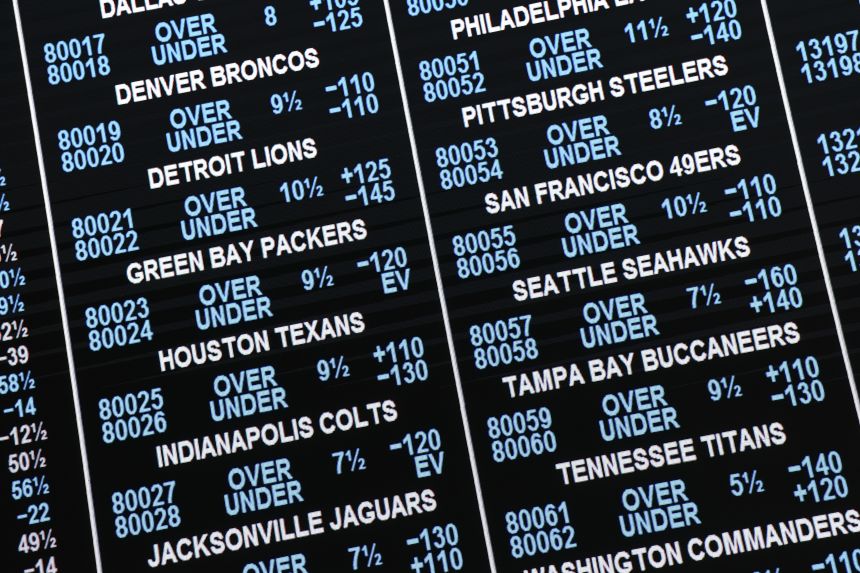

Sports betting has boomed since the Supreme Court opened the door for states to legalize it in 2018, becoming both a business and an ever-present recreational hole in fans’ pockets.

Currently, 39 states and Washington, DC have legal sports betting. For the states, it can be a boon. In the fiscal year that ended March, 2025, New York state reported over $2 billion in gross gambling revenue and over $1 billion in related tax revenue. Last year, Americans wagered nearly $150 billion on sports, a 23.6% increase from the prior year.

That growth is at least partly the result of increased engagement with sports programming. You can’t consume sports podcasts, broadcasts, or studio shows these days without being subject to promotions for digital sports books. And it’s not just in the traditional advertising avenues. Leagues, teams, arenas, media companies, and athletes themselves can, and often do, have official gambling partners. Increasingly, sports content is betting content. And sports themselves sometimes seem like they exist only to serve as fodder for the betting content.

“It’s not good when people’s content is dependent on a paycheck from a bookmaker,” a former employee of a major sportsbook who still works in the industry on the technology provider side, told CNN. “Obviously, gambling happened before it was legal, but now there’s a certain air of desperation, I think, around the promotion of it. It definitely doesn’t make the sports experience more enjoyable.”

Fans, and even practitioners, are taking notice.

A Pew Research Center Study poll from July 2025 showed that 43% of Americans think that legalized sports betting is “a bad thing” for society, up from 34% in July 2022. Only 7% said it’s “a good thing.” The demographic breakdown is even more compelling. Among sports bettors, 34% now say it’s “a bad thing,” compared to 23% in 2022. And among men under 30, 47% now say sports betting is bad for society, more than double the 22% who felt that way in 2022.

“Gambling addiction, it takes away all your will to live.”

Shane

For some of those people, that change is likely the result of realizing that they struggle to gamble responsibly. It’s difficult to get national level data on gambling addiction or problem gambling because there’s no federal research or attention on the problem – most data is collected on a state level. But according to surveys conducted by the National Council on Problem Gambling, 8% of American adults reported experiencing at least one indicator of problematic gambling behavior many times.

“So that’s not just, ‘I gambled too much at a poker game one night.’ That’s, ‘I experienced these behaviors multiple times over the last year,’” Jaime Costello, the NCPG director of programs, told CNN. “And I think 8% of Americans struggling with any behavior is a little concerning.”

According to the NCPG’s reports that track how many people reach out to the helpline via calls or text/chat, there is a spike of outreach in states following the implementation of legalized online sports betting. They note, however, that this could also be the result of increased advertising of the helpline concurrent with the rollout of legalized gambling.

But in the 2024 survey on gambling attitudes and gambling experience, among the key predictors of risky gambling behavior was “participating in sports betting (either traditional sports betting or fantasy sports); gambling online; and being male and/or under the age of 35.”

Sports gambling’s biggest operators, FanDuel and DraftKings, told CNN Sports they’ve worked on technology that will help provide guardrails for gamblers and keep them from making unusually large bets that seem out of character for their accounts. FanDuel and DraftKings both says they are working to provide gamblers with information on responsible usage of their platforms and their rewards programs, which incentivize repeated usage of their platforms, are in line with business norms such as credit card reward points.

CNN Sports put out a call on social media to speak to young men who self-identify as “sports gambling sober” and received more than 100 responses. Some of them had never bet on sports, but many of them were people who had bet on sports, often voraciously, and stopped after realizing they were falling into unhealthy habits. Some of them self-identified as gambling addicts.

CNN Sports spoke to half a dozen of these men, most of whom – like Shane – asked to only be identified by their first names. What follows are some of their stories about the way gambling addictions prey on fandom, the convenience of online sportsbooks, and the masculine culture of competitiveness to corrupt the role of sports in their lives.

Shane, 33, was a closet gambler who hid his growing preoccupation from friends and family. He started betting in 2022, when the Mets won 101 games. Initially, he was able to modulate his gambling based on the games or bets available to him. Some days, he didn’t bet on anything.

But he began to feel like he was missing out on action. So, he bet every game, always on the Mets to win. And then, when they weren’t playing, he bet on other sports too in an effort to artificially replicate the emotional intensity of fandom.

“Once you cross the invisible line, and you don’t really know when you did it, it’s difficult to go back,” Shane said.

That first year, he was gambling so much that he was assigned a personal customer service agent, a feature of sportsbooks intended to keep high spenders – who are not necessarily successful bettors – coming back instead of cashing out.

“And this person would text me like they were my friend,” he said. “They would offer me free things like concert tickets.”

The sportsbook gave him tickets to the New York Rangers playoff series where he was seated next to the players’ wives. He brought his friends and told them tickets were a perk from his job.

By late spring 2023, Shane knew he had a problem. He sought treatment for a gambling addiction and began telling the people close to him about his struggles, “because I was dying on the inside.”

Doing so was difficult. His dad was angry at first – how could Shane have been so stupid to be taken in by something that is so clearly stacked against winning? His social circle was filled with avid sports fans who could engage with their favorite team without jeopardizing their financial lives.

He also got into recovery for alcohol addiction, and “it felt so much easier to call myself an alcoholic than it did to call myself a gambling addict.”

“Gambling addiction, it takes away all your will to live,” he said. “Like, I wasn’t showering, I wasn’t eating. You lose your will to spend money on normal expenditures. I’m in the drugstore, I need to buy shampoo, and I’m looking at the shampoo and I’m like, damn shampoo is $8.99, imagine what I could turn that into.”

Shane was sober for one year. He self-excluded in New York, a process that allows people to ban themselves from legalized gambling within a certain state or a certain app. He receded from his fantasy leagues and stopped watching sports as much. Even after just a year of compulsive gambling, it was hard to watch a game without running bets in his head.

But then in May 2024, he was at a friend’s house in New Jersey, where his self-exclusion had no jurisdiction, and suddenly all the sportsbooks were available to him again. He placed one bet that led to many more.

For the rest of that year, he would take the train to New Jersey to legally place bets.

“It was very sick behavior. Each time (I’ve relapsed) I’ve kind of had to bring my family and the people close to me back in and come clean to them,” he said. “It gets worse and worse each time that you do that because you lose people’s trust.”

He’s sober again now, and has been for close to four months. These days, Shane’s dad controls all of his money; paychecks are deposited not in his own account, but in his dad’s. He calls it a privilege to have someone in his life who can offer that level of trustworthy oversight and credits that kind of protection from himself with being able to watch sports again.

But it’s still hard.

“When I was a kid, sports were this family thing, obviously. They were a tremendous part of my upbringing and also how I learned to build community and connect to other men” he said.

The gambling took a toll on Shane’s relationship with his father, but so has having to curtail his sports consumption: “I know that’s sad to say, because I should be able to connect with him in other ways. And I do, it’s just like, there is one big gaping hole.”

By the time sports gambling was legalized, Ely, 33, had already gone broke betting through offshore sportsbooks while living in Miami, been forced to move back home with parents in New York, and continued gambling on and off despite that humbling surrender of independence.

In 2021, he had a sustained stretch of abstinence. “But then in January 2022, that’s when it was legalized in New York,” Ely told CNN Sports. “And so that was another incentive for me to get going.”

Ely always wanted to work in sports in some capacity. During the nearly decade he spent gambling compulsively, he treated it like work. Even when he maxed out his credit cards, “I still had these delusions that I was going to figure it out.”

The first time his dad, who is in a different recovery program, recommended Gamblers Anonymous was in 2016. That was when Ely, then 23, had to move in with his parents because he had lost all his money on offshore accounts.

“Imagine that, being totally broke,” Ely said, “to reach that point and it still didn’t cross my mind that I was an actual addict. A lot of wasted time.”

Instead, he was convinced that he could make sports gambling work for him if he kept at it. He’d brag about his winnings and offer betting advice to his friends. But at the same time, he hid just how much he was gambling, dedicating nearly every waking hour to it and rationalizing to himself that it was all about to pay off.

“It is so hard to recognize whether you’re just a bad gambler or whether you have a sickness until you’re totally out of money.”

Ely

He set specific rules for himself that he believed would keep his gambling reasonable and even profitable. And then, once he was in action, he would end up breaking all of his own rules. For Ely, the frictionlessness of online sports betting — even when it was through the offshore sportsbooks, it could all be done through your phone — made it difficult to stop.

As a self-described introvert, Ely muses that in an earlier analog era, he never would have reached such a destructive extreme.

“Because the idea of actually leaving my home and having to interact with people and give them my money just to place bets. The extra steps, in my mind, I really can’t even imagine going through that,” he said. “For me, it was the convenience of just waking up and, at any point, being able to place a deposit on my phone, being able to do it all from there.”

In 2023, Ely inherited a significant amount of money from a family member. It gave him the chance to move out of his parents’ place and pursue anything he wanted professionally. “My decision was that was going to be yet another reset on my gambling career.”

Over the subsequent year and a half, he burned through nearly all the money. This past March, Ely had to turn to his parents for help again. He asked them to cover rent, assuring them that work would pick up soon and this was just a stopgap. A few days later, his dad showed up at his apartment unannounced and asked Ely if he was still gambling.

“And I lied to his face,” he said. “I doubled down on the lie that I told him.”

That, combined with having to cancel a trip to Spring Training he had planned to take with friends after he gambled away the money for it, was the wakeup call. On March 17, he attended his first GA meeting. He knew instantly that he fit the criteria of a compulsive gambler. But still, he struggled to want to quit. Finally, on June 12 of this summer, he placed his last bet.

“Ever since, I’ve never opened an app,” he said. “I’ve never signed in to any of my accounts. I never come particularly close to placing a bet. Yes, sometimes I watch games and I think about what I might place under a past scenario. More often, I just think about how crazy it was that I actually thought that I could be successful that way.”

If anything, the experience of acknowledging his addiction and seeking sobriety has brought Ely closer to his dad. He used to feel like his dad’s demons and addiction propensity would never come for him.

“I was a very arrogant person,” he said. “I love my dad so much, but to me, I was like, I’m smarter than my dad, a more intellectual person.”

Now, they discuss how the latest GA meeting went over brunch. Ely evangelizes the merits of the program. And he feels it needs advocates like him.

“Every meeting I go to, I’m one of the youngest people, which is why I’m pretty passionate about the program, because it’s so obvious to me that there are people my age that are going through the same thing,” he said.

“Just from my own experience, it is so hard to recognize whether you’re just a bad gambler or whether you have a sickness until you’re totally out of money. And that’s the experience that so many other people have told me, is that they don’t get help until they literally can’t place another bet. They can’t get help until they’re totally out of ways to gamble again.”

The group chat that Matt, who’s in his late 20s and lives in New York, keeps with his high school buddies is named for the fact that it was initially where they gathered to teach one of the friends about sports. Such an education was deemed critical for a young man.

When sports gambling was legalized, the conversation in the group chat shifted.

“A lot of them gambled less than me, but almost all of them dabbled in it,” Matt said. “And so our conversations about sports changed from just ‘who’s had a good season’ or ‘what person is a choker,’ or something like that, to like, ‘What’s the opening line? What’s it move like?’ A common phrase was, ‘You gotta back the Brinks trucks up for that one.’”

Also a frequent topic: friends in states where sports gambling was not legalized asking him to place bets on their behalf. He estimates that about 70% of the conversation revolved around sports betting.

Matt had never gambled on sports, or anything, before the legalization came to New York, but he had no hesitancy about embracing the opportunity. He was a devoted sports fan with disposable income. Initially, he was moderately successful and relished the excuse to watch games that would have otherwise held no meaning to him.

His girlfriend at the time expressed concern. But Matt dismissed it as a wholesale disapproval of gambling rather than an evaluation of his specific behavior. She thought any amount of gambling was a problem.

“Which is correct,” Matt said with hard-won hindsight. “She was right.”

The relationship didn’t last.

His dad cautioned against it as well, reminding Matt that even if he was winning now, it wouldn’t last.

“Also correct,” he said.

With his friends, Matt downplayed how extreme his betting had become over time. Occasionally, he would let it slip how much money he had on a particular outcome and the group chat would react in what he described as a “guy way”: Yo, man, that’s crazy! Damn, that’s wild. But if they were looking for reasons to be worried about the financial implications of such audacious bets, Matt was careful not to give them any.

“If I won, I told the truth,” he said, “and sometimes I lost big, and I would lie about that.”

The biggest loss came in December 2023.

“Of course I remember it,” Matt said. “It was Steelers-Patriots.”

He watched the game alone, at work. And as the bets he placed started to unravel, he doubled and tripled down, desperate to recoup. In the end, he lost $60,000 on that one game.

What did it feel like to lose so much on a game over which you have no control?

“It’s much closer to drowning than it is to being shot,” Matt said.

For Matt, that was rock bottom. He admits that he may not have quit cold turkey right away, unwilling now to check the record out of concern for the dark feelings that would dredge up. But soon after, he stopped betting and, for a time, stopped watching sports entirely. He estimates that he went two months without turning on a game, until the Super Bowl later that winter.

“That was by far the longest I’d gone without watching, especially the NFL, in my entire life,” he said. “And I probably didn’t talk to my friends, because they were talking about sports all the time.”

They didn’t notice, at least not right away. Pretty quickly, Matt committed to keeping up appearances.

“Actually, I lied more to people when I was sober than when I was then when I wasn’t,” he said. Like when he watched the Super Bowl that season. “I probably lied about what I had on the game.”

It wasn’t until the following NFL season, when one of his friends asked in the group chat for Matt to place a bet for him, that he started coming clean. Even now, he realizes he never told his family or many people close to him anything definitive about his gambling, caught in between not wanting gambling to be his identity and knowing that it was.

“Emphatically, it was a mistake to start. And I don’t even mean that because of the losses, it made me a worse person. It made me someone who was just known as a gambler. Which, that sentence grosses me out, like I never wanted to be a gambler,” Matt said.

It made him at once more volatile and less interesting. His moods and his time were defined by the bets he was placing. “But also, it was part of my identity for a long time, and is part of how I talked to (my friends). Like, that was part of our language, was just betting.”

These days, the gambling chatter in the group text has been replaced by more general sports conversations, the way it was before legalized sports betting. As he talked about it, Matt realized that perhaps his friends, most of whom still gamble, had taken their conversations of spreads and backing up the Brinks trucks to a separate space, without him.

“Which is all fine for me,” he said.

Nick Goerg, 35, knew as soon as legalized sports betting came to New York that it was “the beginning of the end for me,” he said.

He had been placing bets through a bookie since college. As an adult, he built a social identity around being willing to risk increasingly large sums of money on sports, to the gobsmacked entertainment of his friends.

“Because it’s always a competition with guys. It’s like, who’s doing the most? Like, who’s being the most ridiculous? And that was part of my thing,” Goerg said. “Everyone was like. ‘How much does Nick have on this game? Or, ‘What is Nick betting on now?’”

With legalization, he started betting more money and more often, staying up late into the night, placing bets on Turkish basketball at 3 a.m. and becoming numb to anything less than $100. He became a VIP, the status that earns

He wasn’t shy about his gambling, boasting to his then-girlfriend that he could do it professionally and posting his wins on social media. At the time, he thought he was a great sports gambler, but the perspective of giving it up entirely has forced him to reckon with the reality.

“If you’re looking at my lifetime winning and losses, I would venture to assume I’m probably down over six figures,” he said. “The fact that I can tell you that right now, and smile, is cathartic.”

The turning point came in April 2023, the final weekend of March Madness. His then-girlfriend, now wife, was away. He’d just closed a big deal at work which, when deposited along with his paycheck that Friday, gave him roughly $27,000 in his bank account.

“I just felt like I let something get the best of me, and now I couldn’t participate like everybody else.”

Nick Goerg

On Saturday morning, his cousin invited him to a boozy brunch.

“I start drinking, the Final Four starts, and I’m placing, like, $10,000 at halftime,” Goerg said. “And I didn’t win a single bet.”

This time, he didn’t tell his friends what he was doing on his phone. He went home and didn’t sleep, drinking and doing cocaine through the night. By Sunday, Goerg estimates that there was $10 left in his bank account.

“I eventually went into the bathroom, literally looked at myself in the mirror, and I just started crying. And I remember saying to myself, I quit,” Goerg said. He called his girlfriend and confessed that he had a gambling problem.

Goerg never placed another bet. He self-excluded from the sportsbooks on April 20, 2023. Concurrently, he also stopped drinking and doing drugs. At first, when telling friends and family about his sobriety, Goerg led with the sobriety from substances instead of sports betting.

“I just felt like I let something get the best of me, and now I couldn’t participate like everybody else,” he said.

His friends still gambled and meanwhile, he had stopped watching sports entirely because the commercials for sportsbooks made him anxious and angry. During the height of his gambling addiction, he had been a “VIP” with a dedicated host who encouraged him to place bets at both FanDuel and DraftKings, a practice that is now the subject of lawsuits. Now, Goerg felt lonely, and like a sucker for having believed he could beat out the sportsbooks that are designed to separate fans from their money.

“Such a sucker,” Goerg said.

He had been a sports fan ever since his grandfather had taken him, then six years old, to a Knicks game. The memory of walking onto the court at Madison Square Garden and leaving with Charles Oakley’s autograph was still vivid.

“They ruined that for me,” he said. “They nearly took that away from me. So it became, like, very personal.”

Goerg wasn’t ready to give up on sports. The first sports he watched after quitting gambling were the 2024 NFL championship games. When the San Francisco 49ers came back to beat the Detroit Lions late in a close contest at home, he was struck by just what a good game it had been.

It was practically cinematic, and Goerg found himself wondering how it compared – not the results, but the experience and the aesthetics – to the dozens, if not hundreds, of other games he’s watched in his life. He wanted a forum to appreciate what he had seen as a pure entertainment product. A space for sports fans to congregate without any kind of gambling presence.

With his now-wife’s blessing to recenter sports in his life, Goerg built an app, called Rate Game, that functions like Letterboxd for sports, inviting fans to grade individual games and write reviews of the viewing experience. It launched just in time for March Madness 2024. Last month, December 2025, they set a new Rate Game record with 2,160+ monthly active users.

These days, Goerg watches sports regularly. And remarkably, for someone who nearly saw his life destroyed by the dangerously compelling mercurial nature of the outcomes, he enjoys it.

“I would say it’s fun because I am in a place where I can love the story lines again,” he said. “I can enjoy the buzzer beaters, and not even in the back of my mind am I like, ‘Oh, my God, I would have won or lost money based on that shot.’ So I’m really proud of that.”

Culpability is a tricky question with problem sports gambling.

In conversations, many of the recovering self-described gambling addicts CNN spoke to made analogies to alcohol. Several of them reasoned that they didn’t think bars or beer should be illegal despite the dangers of alcohol addiction. They acknowledged that many people can bet responsibly. They were introspective and honest about the parts of their personalities that might have made them prone to letting it go too far.

But the culture does prime young men to align themselves emotionally with sports and then offer them the trapdoor of an opportunity to return on that investment. And many of them said they feel the sportsbooks themselves are pernicious in their tactics.

Ely mentioned that he would like to see the apps install guardrails, perhaps to limit the number of deposits someone can make in a certain timeframe, which he compares to the bartender’s discretion to cut someone off if they appear overly inebriated.

“I think that would give gamblers more space to think for themselves in terms of what they’re going through,” he said.

FanDuel, the largest of the online sportsbooks, says it’s trying to implement some version of those guardrails. In a conversation with CNN Sports, Senior Vice President of Public Policy and Sustainability Cory Fox touted a technology rolled out last year that sends an alert if users try to make a deposit that appears out of line with a machine-learning projection for that particular user on that day.

These “real-time check-ins” are part of FanDuel’s responsible gaming technology. Deposits of a certain magnitude will trigger a check-in that requires users to set a deposit limit — but the users themselves still control of setting that deposit limit.

“It’s still ultimately about empowering users to manage their play, but we think it’s a strong way to nudge them towards the kind of play that is appropriate for them,” Fox told CNN Sports.

Why professional athletes love to gamble

They earn millions so why gamble for thousands? Insiders say for pro athletes, it’s less about the money than the mix of competition, culture and nonstop access.

Why professional athletes love to gamble

1:17

There is also a responsible game operations team that reviews users who have been flagged through an automated system as a possible danger to themselves. There are a range of actions that can be taken based on severity, up to and including FanDuel excluding users. Fox declined to share how often that step is taken.

“Yes, when you gamble, you may lose, but we want you to lose an amount that is fun and entertaining for you,” Fox said. “That you can do for years out into the future.”

Regarding the use of VIP programs to incentivize bettors, Fox noted that hosts are trained regularly on responsible gaming and are not compensated on the basis of how much their specific clients are betting in the app.

DraftKings provided a statement to CNN that reads, in part, “We make tools and educational resources available to all customers to help them make informed decisions. Furthermore, loyalty programs are a standard part of most consumer-oriented businesses, from grocery stores to credit cards, and our program is no different, rewarding loyal adult customers who enjoy engaging with our sportsbook.”

But even more than a specific app interface, the men repeatedly returned to the sheer omnipresence and, indeed, often full-throated celebration of gambling in sports.

“You cannot watch a game without seeing it on the court. Either on the literal court, this is like ‘FanDuel Court,’ or on the jersey, or during commercials or during halftime,” Goerg said. “And what it’s actually doing is, it’s a quiet erosion of sports for just competition between two teams, where there’s a winner and a loser.”

“I quit in ‘23 and it’s only gotten larger,” Matt said about the presence of gambling in sports, “which is kind of crazy to me.”

Costello, the director of programs at the NCPG, said there are a couple of factors that make modern gambling addictions so difficult to assess and treat. For one thing, money is still a relatively taboo subject. And winning can mask risky behavior. If a bet pays off, it can be hard to convince someone that placing it was detrimental to their health.

Beyond that, unlike drug or alcohol abusers, gambling addicts can’t entirely remove money or phones from their lives.

And, for all the men that CNN spoke to, they don’t want to remove sports, which feels integral to their sense of community and self. They love sports. They want to watch the game without being reminded of the worst moments in their lives or tempted to go back there. For now, they’ve found a way forward. Increasingly, though, that feels like too much to ask.

As Shane said: “Sports themselves have almost become more of a vice.”