Subscribe now for full access and no adverts

By the end of the 19th century, around 120 County Asylums were operating across England and Wales (Scotland had its own system of Royal and District Asylums). They were mainly constructed under the auspices of two key pieces of legislation – the County Asylums Act and the Lunacy Act, both passed in 1845 – and were intended as a progressive step, representing a publicly funded and properly regulated alternative to previous approaches to mental health care (see box below). Despite these worthy intentions, however, such institutions rapidly became associated more with confinement than with effective treatment. Since the development of ‘care in the community’ policies in the 1980s, though, most of these complexes have now closed, their buildings converted to other uses or demolished altogether. While plentiful documentary evidence survives to testify to how these sites operated, archaeological remains can offer thought-provoking insights into the experiences of those who lived and worked within their walls.

Such tangible traces were uncovered on the site of what would ultimately be known as Clifton Hospital, at Clifton Ings, a north-western suburb of York. There (working for Jacobs UK Limited and BAM Nuttall on behalf of the Environment Agency), York Archaeology carried out excavations and watching briefs ahead of flood defence improvements along the River Ouse. These investigations, undertaken in riverside fields directly to the north and west of the former hospital, uncovered features spanning many centuries, from ditches containing Iron Age and Romano-British pottery to evidence of medieval ridge-and-furrow farming. Most significant for the subject of this article, though, was a rubbish dump and other finds relating to the hospital’s earlier incarnations serving the North and East Ridings of Yorkshire. Its contents provide poignantly personal echoes of some of the institution’s occupants, as well as highlighting how attitudes towards mental health had evolved over the site’s lifespan.

The main entrance to what was then known as the North Riding Lunatic Asylum, later Clifton Hospital, pictured in around 1900. Image: reproduced with the permission of Borthwick Institute for Archives, University of York

The main entrance to what was then known as the North Riding Lunatic Asylum, later Clifton Hospital, pictured in around 1900. Image: reproduced with the permission of Borthwick Institute for Archives, University of York

The evolution of Clifton Hospital

The story of institutionalised mental health care in the York area begins long before the foundation of the Clifton complex. The subscription-funded York Lunatic Asylum (later Bootham Park Hospital) was founded just outside the city walls in 1777, followed two years later by the Quaker-run York Retreat (which, in stark contrast to the squalid conditions for which the former site became notorious, pioneered a more compassionate approach, eschewing restraints and physical punishments and emphasising the dignity of its patients). Local authorities for the West Riding of Yorkshire established a County Asylum in Wakefield in 1818, but it was not until 1843 that the councils of the North and East Ridings decided to jointly found a Pauper Lunatic Asylum of their own at Clifton.

The hospital boundary wall. Much of the complex was demolished following its closure in 1994.

The hospital boundary wall. Much of the complex was demolished following its closure in 1994.

Designed by George Gilbert Scott and William Bonython Moffatt (architects who worked on many other asylums and workhouses across the country), the Clifton institution was built on the ‘Corridor’ layout that was typical of the time, and officially opened in 1847. The need for its services was immediately obvious – within two years the complex had to be extended, and it continued to expand through the 19th and 20th centuries, with the addition of various wards, staff cottages, and a chapel reflecting the growing number of patients in residence. Like other asylums of the period, the Clifton site was designed as a separate, self-contained community, with its own recreation facilities (including a cricket pavilion) and a farm complex to support its activities and provide purposeful outdoor work for its population. It is clear from hospital archives that gardening and horticulture were used as a therapy for the patients until the 1960s, and during York Archaeology’s excavations the discovery of abundant nails suggested that plants had been trained against a wall within the hospital grounds.

The nurses’ home associated with the 19th-century hospital at Clifton Ings. Image: reproduced with the permission of Borthwick Institute for Archives, University of York

The nurses’ home associated with the 19th-century hospital at Clifton Ings. Image: reproduced with the permission of Borthwick Institute for Archives, University of York

Documentary sources also attest that the institution changed its name three times during its lifetime, shown on Ordnance Survey maps throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Beginning as the North and East Ridings Pauper Lunatic Asylum, in 1865 the site became the North Riding Lunatic Asylum in 1865, then the North Riding Mental Hospital in 1920, and finally Clifton Hospital when it joined the then-newly founded NHS in 1948. After the application of ‘Care in the Community’ policies, the hospital eventually closed in 1994; parts of the complex were swiftly demolished, but some services remained operational until 1996. The hospital laundry, meanwhile, remained standing until the early 2000s, and the chapel, Pavilion Cottages, and cricket pavilion can still be seen, though they are mainly in residential use now.

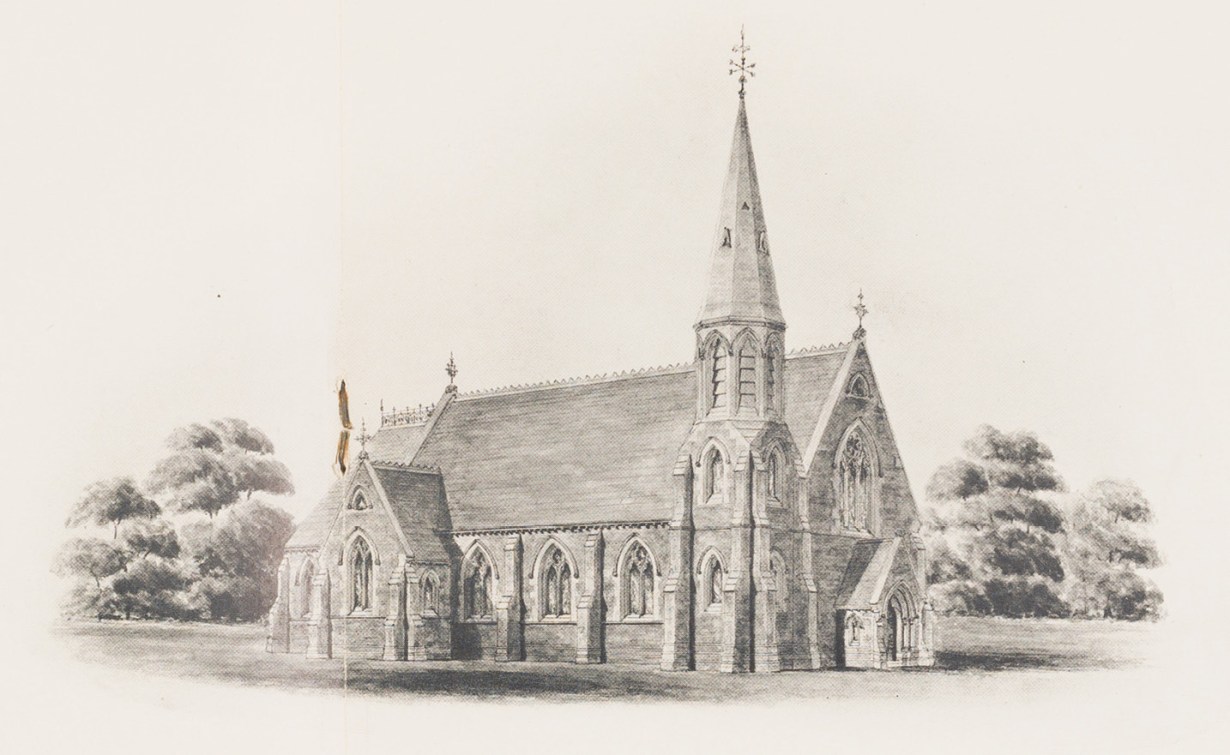

The Clifton complex’s chapel, built in 1873. Image: reproduced with the permission of Borthwick Institute for Archives, University of York

The Clifton complex’s chapel, built in 1873. Image: reproduced with the permission of Borthwick Institute for Archives, University of York

Stamps of authority

Today, Clifton Ings is home to the private Clifton Park Hospital (established in 2006), continuing the site’s long medical legacy. Earlier episodes in this story were vividly illustrated by the contents of the rubbish dump mentioned at the start of this article. Ranging from eating utensils, a jug, and crockery to more intimate items (such as a toothbrush) and objects relating to leisure, the finds include an electroplated spoon bearing the BENARES mark of John Round & Son of Sheffield, dating to the 1890s. Alongside these objects, one of the more unusual components of this collection was a trio of dominoes. Dominoes are rarely found on archaeological sites, and these examples (analysed by Ian Riddler) were particularly noteworthy as they were crafted from multiple materials, with bone faces joined to wooden bases using copper-alloy pins. Their elegant design suggests that these items may have belonged to a specific individual, rather than to the hospital – in stark contrast to the much more utilitarian pottery that was uncovered within the rubbish dump as well.

Some of the small finds from the rubbish dump, including a stamped spoon dated to 1890, a toothbrush, and three bone-and-wood dominoes.

Some of the small finds from the rubbish dump, including a stamped spoon dated to 1890, a toothbrush, and three bone-and-wood dominoes.

Much of the pottery assemblage (analysed by Anne Jenner and Katherine Bradshaw) contained items related to dining – plates, bowls, cups, an enamelled jug – alongside stoneware storage jars and part of a flagon with its stopper still in place, possibly a hot-water bottle. There were also two sherds with a conical foot that could have come from vessels used to contain medicines (similar forms have been used elsewhere as syrup jars). The crockery varied from very plain, white earthenwares to finer, more colourful and decorative pieces, possibly reflecting different sets used by patients and those that were reserved for staff/visitors, or perhaps different social classes of patients. Some of the more basic vessels have simple, coloured banding around the rim, but these were nevertheless cheaply produced, plain vessels reflecting the small budgets available for running hospitals like that at Clifton. Most interestingly, some of the most basic ceramics (used for eating, drinking, and administering medicines) also bear decorative stamps with the hospital’s name. Although most of the stamped sherds come from the same context, three different designs reflect how the institution’s name had changed over time – again hinting at a lack of funds, which had driven the reuse of older items even after their labels had become outdated.

The first two stamps give the site’s name in full: ‘NORTH RIDING YORK ASYLUM’ and ‘NORTH RIDING MENTAL HOSPITAL’. Both of these use the same, plain form, though there are hints of different batches even within consistent designs – one example seems to have the ‘S’ in ‘ASYLUM’ as a later addition. There is also a later, abbreviated stamp that reads ‘NRMH’ with a stylised motif around the letters, creating a slightly more decorative ‘logo’. As well as illustrating the hospital’s own history, these changes of name evoke how attitudes towards mental health and mental health care had changed over the period that the site was in operation. The archaeology of the Clifton Ings site presents this story in a tangible way, giving more nuanced insights into the everyday activities and personal stories that it witnessed. As we examine items that were used by the people who lived within the complex’s walls, we are encouraged to think of them not just as patients, but as members of a community with friends, families, routines, and hobbies.

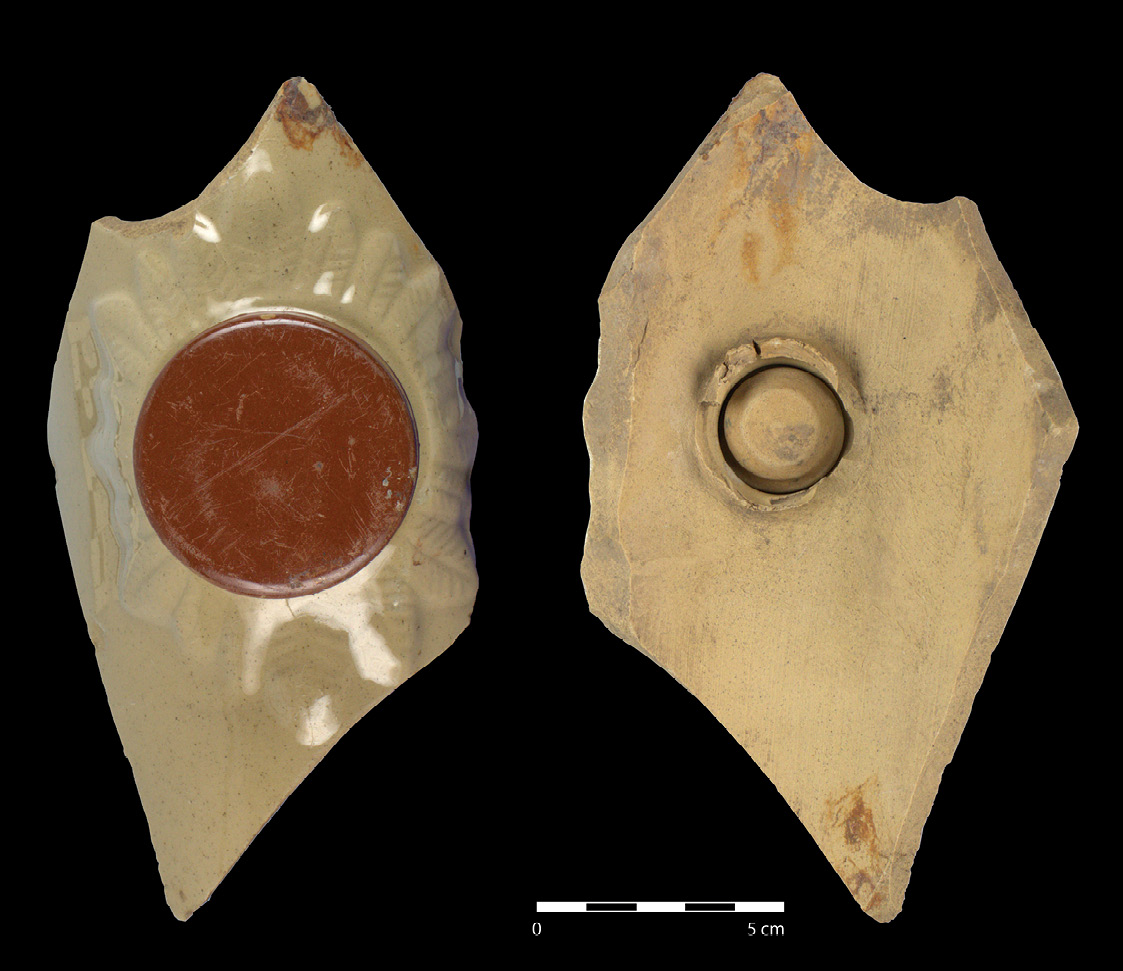

Above & below: Further finds from the Clifton Ings excavation: a jug with an enamelled handle, and a fragment of what has been interpreted as a ceramic hot-water bottle.

Above & below: Further finds from the Clifton Ings excavation: a jug with an enamelled handle, and a fragment of what has been interpreted as a ceramic hot-water bottle.

Jane Stockdale, curator of the Mental Health Museum in Wakefield (which itself was originally founded on the site of the West Riding Pauper Lunatic Asylum, later Stanley Royd Hospital, and is now based at Fieldhead Hospital; see http://www.southwestyorkshire.nhs.uk/mental-health-museum/home for more information), believes that the Clifton assemblage is important not only for showcasing the history of one specific hospital, but also those like it around the country. ‘The collection of objects relating to the story of mental health treatment is unusual, so these finds from Clifton Hospital represent an important and rare assemblage,’ she said. ‘At the Mental Health Museum we know the power of objects in telling us not only about historic practice but also enabling us to reflect on experiences today. Objects can be a way for us to talk about difficult subjects and challenge stigma. The objects from Clifton Hospital, for example the domino and toothbrush, are particularly interesting as they are everyday items. When exploring institutional histories, it is sometimes hard to get a sense of stories from the patients’ perspectives. These items give us a powerful insight into moments of leisure and the day-to- day lives of individuals.’

Evolving attitudes

As well as through archaeological evidence from sites like Clifton Hospital, attitudes towards mental health in England can be traced, to an extent, through the legislation that was passed in relation to how institutions operated, and shifts in terminology used to describe such establishments and their patients.

In the post-medieval period, concepts of mental illness moved away from ideas of divine punishment or demonic possession towards social and environmental factors, as well as questions of heredity. Stigma and superstitious thinking persisted for a long time, however, and with little understanding of the actual causes of mental ill-health, attempts at treatment focused on the body rather than the mind, and tended to be punishingly physical, including restraints, purges, cold-water baths, and bleeding.

More decorative wares from the pottery assemblage, contrasting strongly with the utilitarian examples shown right. Do they reflect ‘fancier’ crockery being used for visitors or staff, or different social classes of patients?

More decorative wares from the pottery assemblage, contrasting strongly with the utilitarian examples shown right. Do they reflect ‘fancier’ crockery being used for visitors or staff, or different social classes of patients?

In London, the Priory and Hospital of St Mary of Bethlehem (popularly known as ‘Bedlam’) had been admitting mentally unwell individuals since the 14th century, but most people relied on friends or family to care for them at home. Early legal measures such as the 1601 Poor Relief Act made it the responsibility of the parish to care for those too old or ill to work, but this generally meant that the poorest mentally unwell people were confined in prisons or poorhouses.

The 1700s saw the rise of a notorious new phenomenon: the private ‘madhouse’. These establishments were completely unregulated and were run as commercial businesses, with their keepers (who were rarely medically qualified) paid to house ‘insane’ individuals. Public fears that ‘sane’ people were being unlawfully committed to such places by unscrupulous spouses or relatives sparked the 1774 Madhouses Act, which required private institutions to be licensed and inspected annually by a committee from the Royal College of Physicians (or, outside London, by local Justices of the Peace), as well as requiring medical certification for any new admission.

Another important step came with the 1808 County Asylums Act, which allowed local authorities to build accommodation for ‘pauper lunatics’ at public expense. Council uptake was, however, slow until the 1845 County Asylums Act made their construction compulsory, creating a national network overseen by the newly formed Lunacy Commission. Like their predecessors, these institutions were intended to keep mentally ill people separate from wider society, but their secluded, often rural settings were also meant to benefit their residents. Designed as self-sufficient communities, these complexes offered patients purposeful (and useful) occupation in on-site kitchens, laundries, workshops, and farms, as well as recreational activities.

This stamped pottery shows the hospital’s name changing over time – itself reflecting changing attitudes to mental health treatment.

This stamped pottery shows the hospital’s name changing over time – itself reflecting changing attitudes to mental health treatment.

The word ‘asylum’, meaning ‘refuge’, signals the good intentions of this movement, but the longstanding tension between care and confinement was not resolved, and with overcrowding being a frequent problem, poor treatment and unsanitary conditions were reported at many institutions. Successive legislative changes brought further regulation, among them the 1890 Lunacy Act, which restricted the classification of ‘lunatics’, and therefore reduced the number of people eligible for admission, as well as making further provisions to prevent wrongful confinement, strengthen inspection powers, and further restrict private asylums.

The early decades of the 20th century saw an outpouring of experimental approaches to mental health treatment, from psychoanalysis to now infamous physical interventions like insulin shock therapy and psychosurgery (lobotomy). Legal writings of the time continued to use terminology that would be considered offensive today, but the 1930 Mental Treatment Act specifically replaced the term ‘asylum’ with ‘mental hospital’ in law, while the 1959 Mental Health Act changed mentions of ‘lunatics’ to people with ‘mental disorder’. This latter Act aimed to remove distinctions between psychiatric and general hospitals, making treatment more easily available, and to shift the emphasis from institutional care towards a more empowering ideal: care in the community. It would take decades for this last ambition to be fully realised, but the 1983 Mental Health Act strengthened patients’ rights by introducing ideas of consent in their treatment, and a gathering momentum towards deinstitutionalisation culminated in the NHS and Community Care Act 1990, which saw many former asylums closed for good.

Further reading:

• To read more about the history of County Asylums, and for details of individual institutions, see http://www.countyasylums.co.uk.

• Borthwick Institute for Archives, ‘Administrative/Biographical’, Clifton Hospital Archive: http://archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/data/gb193-nhs/clf.

• Historic England, ‘The licensing of madhouses’, The Age of the Madhouse – Home of the Well-Attired Ploughman: https://historicengland.org.uk/research/inclusive-heritage/disability-history/1660-1832/the-age-of-the-madhouse.

• A Takabayashi (2017) ‘Surviving the Lunacy Act of 1890: English psychiatrists and professional development during the early 20th century’, Medical History 61(2): 146-169: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5426304.

All images: York Archaeology, unless otherwise stated