It has become common for adolescents and children in psychiatric distress to be “boarded” in ED corridors, often for days, because no psych beds are available.

It has become common for adolescents and children in psychiatric distress to be “boarded” in ED corridors, often for days, because no psych beds are available.

The widespread “boarding” of children and adolescents in emergency departments while awaiting psychiatric beds is not merely a logistical failure but a profound ethical one—and evidence that the U.S. has allowed its continuum of mental health care to collapse—according to a commentary by LDI Senior Fellow Dominic Sisti, PhD, MBE in the Journal of Adolescent Health.

The commentary comes in the wake of a growing number of other expressions of concern about the issue, including a report in the August JAMA Health Forum that found boarding may disproportionately affect youths enrolled in Medicaid, which covers more than 35 million children and adolescents, almost half of all youths in the U.S. It also found that 1 in 10 visits by patients with suicide-related behaviors and depressive disorders resulted in three to seven days of boarding in the emergency department.

Dominic Sisti, PhD, MBE

Dominic Sisti, PhD, MBE

“Boarding” occurs when an ED decision has been made to either admit or transfer a young patient for psychiatric hospitalization, but the patient remains in the ED, often for extended periods, because no psych unit bed is available.

Worse Outcomes

It is widely acknowledged that long boarding periods spent in the often chaotic and makeshift conditions of the ED can worsen a young patient’s psychiatric condition and prospects.

“This issue has reached alarming levels across the U.S.,” Sisti said in an LDI interview. “One driver is that hospitals are disincentivized from investing in pediatric psychiatric beds under the current reimbursement models. Unlike with medical procedures, they do not get reimbursed for mental health care at a rate that incentivizes more investment. You have to ask yourself why this happens with mental health care but not with cancer or other health conditions. Mental illness is highly stigmatized, and those attitudes are reflected in budgets, policies, and practices.”

Sisti is an Associate Professor in the Department of Medical Ethics & Health Policy at the University of Pennsylvania. He directs the Scattergood Program for the Applied Ethics of Behavioral Health Care and holds secondary appointments in the Department of Psychiatry, where he directs the ethics curriculum in the residency program, and the Department of Philosophy.

Not a “Logistial” Problem

His commentary, co-authored with Sejai F. Shah, MD, of Harvard Medical School, noted that “although often discussed as a logistical or operational problem, psychiatric boarding … illustrates the failure of policymakers and health care business leaders to honor a basic postulate of medical ethics in a just society, that individuals with a serious mental illness … deserve timely, appropriate, and effective treatment in a therapeutic setting.”

The piece goes on to say the services needed by these patients range from outpatient therapy and day programs to residential treatment and acute and long-term hospitalization.

Cited barriers to appropriate care include:

• The disappearance of many intermediate and inpatient options

• Chronic underfunding of programs that do exist

• Waitlists for outpatient services that stretch up to two years

• Lack of affordable housing for parents and caregivers

• Ethically fraught situations confronting clinicians involving restraints, sedation, and premature discharge

• Large cuts to Medicaid and social service spending that are worsening the situation

Potential Solutions

The authors highlight partial solutions, including structured stabilization protocols, treating boarding time as treatment time, trauma-informed ED psychiatric units (such as the Emergency Psychiatric Assessment, Treatment, and Healing (EmPATH) model), and better-designed therapeutic environments. But they stress these are stopgaps. Lasting improvement requires rebuilding a full continuum of care—from outpatient services to inpatient beds—along with confronting community resistance to psychiatric facilities and recommitting politically and financially to children’s mental health.

Author

More LDI News

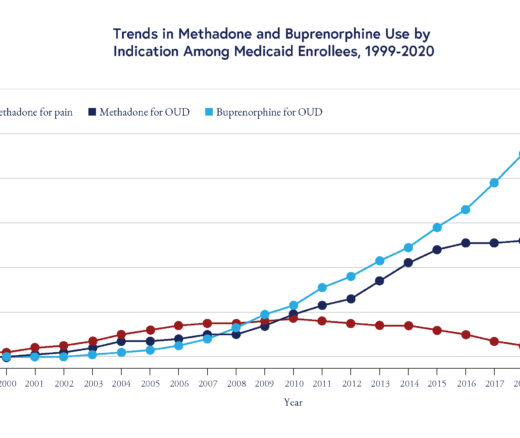

Methadone Use Rises—But Too Few People Get Opioid Medication

Chart of the Day: Methadone Use for Opioid Use Disorder Tripled From 2010–2020, Yet Only One in Four People With Addiction Receive Medication

February 4, 2026

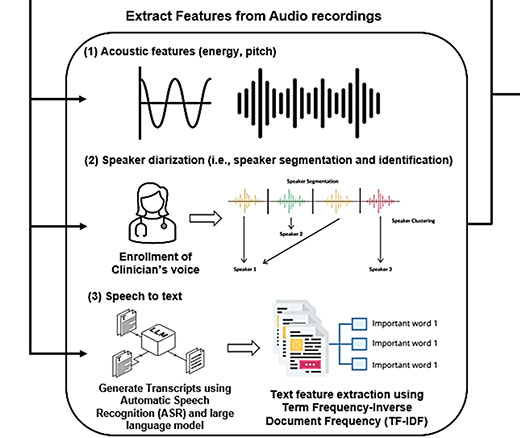

Can AI Hear When Patients Are Ready for Palliative Care?

Researchers Use AI to Analyze Patient Phone Calls for Vocal Cues Predicting Palliative Care Acceptance

February 4, 2026

Medicare’s Hidden Fix for High Drug Costs

Medicare’s Payment Plan Can Ease Seniors’ Crushing Drug Costs but Medicare Buries it in the Fine Print

February 3, 2026

Six Insights on Health Care Affordability From Penn LDI

LDI Fellows’ Research Quantifies the Effects of High Health Care Costs for Consumers and Shines Light on Several Drivers of High U.S. Health Care Costs

February 2, 2026

Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Repeal of Minimum Staffing Standards for Long-Term Care Facilities

Comment: Submitted to Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

February 2, 2026

Can AI Be Licensed the Way Doctors and Nurses Are?

A Licensure Model May Offer Safer Oversight as Clinical AI Grows More Complex, a Penn LDI Doctor Says

January 29, 2026