For three years, Katie Lyon-Pingree watched the black bin on her dining room counter fill up with paperwork: insurance claims tallying her son’s suffering in dollars and denials, ambulance bills from his emergency room visits and his hospital discharge papers that never felt like a real release.

Despite every effort to get her 18-year-old son, Matthew Pingree, the mental health care he needed, nothing seemed to work. In 2021, Matthew lost his battle with mental illness.

Pingree wore multiple hats as she continued to care for her other two children throughout her son’s struggles.

“I didn’t have the luxury to heal,” Pingree said, revisiting the files that accumulated from Matthew’s treatment and slamming them onto the dining room table in frustration. “It was like I had to have two brains, basically. I was the care coordinator, too. It was overwhelming.”

New Hampshire offers a wraparound service called Families and Systems Together, or FAST Forward, that is designed to support families when a young person is experiencing serious mental and behavioral health challenges. The program provides coordinated care from school counselors and therapists to caregiver respite, individualized plans and any other support a family might need.

But Pingree said she was never made aware of this service during her son’s struggle with mental health, despite the many interventions he received.

A bill sponsored by Senator Regina Birdsell, Senate Bill 498, aims to close the private health insurance gap for children’s behavioral health. A revival of last year’s effort, the bill would ensure that insurance companies share the fees associated with providing wraparound services, rather than leaving families or the state to bear the full financial burden.

If passed, the bill would require any health insurance carrier in New Hampshire that covers adolescents to contribute a proportional share to fund the program, ensuring these vital services are accessible to families like the Pingrees, who live in Bow.

Michele Merritt, president of New Futures, a public health advocacy nonprofit, said getting private insurance providers to cover these services has been a five-year fight.

When insurers don’t provide coverage, families can apply for a Medicaid waiver, but only if their child’s mental health condition is severe enough to put them at risk of hospitalization.

“Private health insurance carriers are saying that they don’t typically pay for non-clinical services, and I find it offensive, because it is a service that is necessary for a child who has mental illness to be able to stay in their home safely with their family,” said Merritt.

When children don’t qualify for Medicaid waivers, the state steps in, spending around $2 million each year from New Hampshire’s general fund, according to New Futures.

‘What do we do as parents?’

There was more to Matthew than his mental health diagnosis. He was on the wrestling team at Bow High School. He loved chess and space. He was an active Boy Scout.

Pingree remembers a trip to Vermont when Matthew was learning to drive. She had two phones open, playing an online chess game on his behalf. From the driver’s seat and without looking at the screens, Matthew guided her through every move, winning the game effortlessly against his mother.

A photo of Matthew Pingree Credit: ALEXANDER RAPP / Monitor

A photo of Matthew Pingree Credit: ALEXANDER RAPP / Monitor

“He was very intelligent, too smart for his own good, which was honestly one of the struggles we had with therapists who just couldn’t intellectually keep up with him,” said Pingree.

When Matthew was 14, Pingree said she knew something was wrong, but she couldn’t pinpoint the issue. In 2019, Matthew confided in his school psychologist that he had made a plan to take his own life.

What followed was a blur of hospital admissions, therapy appointments and mounting medical bills.

In the months that followed, Matthew made another attempt to take his life, but this time, Pingree and her husband managed to intervene in time.

They slept on the floor in his room that night, staying by his side to keep him alive.

They refused to take Matthew to the emergency room because of a previous trip that haunted them. Eventually, the Pingrees sent Matthew to a residential treatment facility in Utah, navigating the process entirely on their own.

Credit: ALEXANDER RAPP / Monitor

Credit: ALEXANDER RAPP / Monitor

When they visited him the first time, he barely acknowledged them.

“We literally sat in a room at a table for five minutes while he gave us the cold shoulder, and then he got up and walked out,” Pingree said. “That was the extent of our first visit.”

Pingree believes that if wraparound services had been available in their own state, Matthew could have stayed at home, surrounded by the love of his family and the support of his community. She might have had the chance to rebuild her relationship with him, instead of watching his anger grow toward the very people who wanted to help him.

“The system we have is a joke. It is an insult to families,” Pingree said about her family’s options in New Hampshire. “What do we do as parents? I’m just flailing around as best I can.”

After ten months in Utah, Matthew returned home, but things still weren’t okay. He would pace around the kitchen in a manic state, lash out at his younger brother and cut himself off from the family.

“There wasn’t a lot of sort of normalcy and places for connection,” Pingree said, her mouth quivering as she struggled to hold back tears. “Genuinely, towards the end, I was afraid of him. I was afraid to be in the house. It was extremely tense in here.”

After returning home, Matthew graduated from school and even enrolled at the University of New Hampshire, but only for three months before dropping out. For a while, it seemed like things were finally starting to settle, like a fragile sense of stability was returning.

On a December morning in 2021, when Pingree texted him as she usually did, he didn’t respond. It wasn’t the first time he had been slow to reply, so she went up to his room, expecting to find him getting dressed, just like any other day.

She entered the room to see an open window letting in the sharp December air and her son laying motionless on the floor.

His skin had lost all color, his body was already stiff.

The reality of Pingree’s loss didn’t fully hit until the police and EMT personnel arrived. Then, she understood, with a crushing finality, that her son was gone.

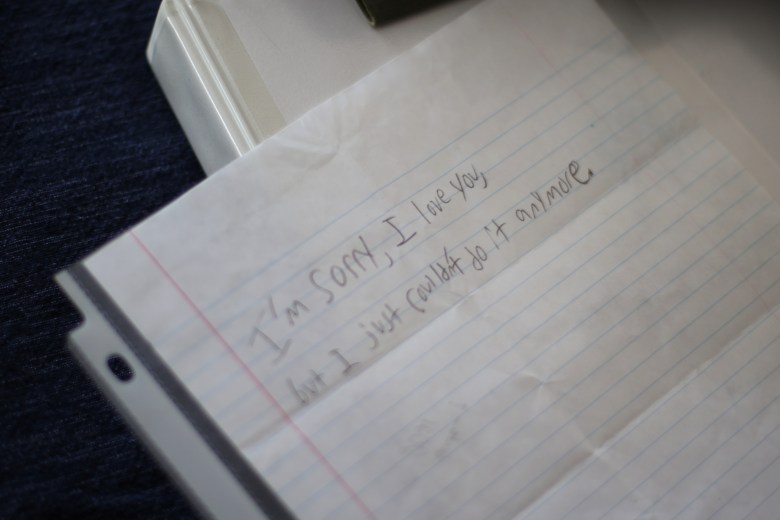

As she sifted through his belongings in the months after, she found a note from Matthew, written with a heartbroken simplicity: “I’m sorry, I love you. I couldn’t do it anymore.”

A note Matthew Pingree wrote months before he died Credit: ALEXANDER RAPP / Monitor

A note Matthew Pingree wrote months before he died Credit: ALEXANDER RAPP / Monitor

Years have passed, but Pingree hasn’t forgotten. She wants to make sure no other family faces the same struggles she did, navigating a maze of services that either weren’t known to her or were blocked off by insurance.

She plans to testify on Wednesday at the bill’s public hearing.

“If I think too hard about the what-ifs, that’s what kills you. I didn’t even know the services had existed until after he died,” she said. “It’s hard to know if it would have helped. I’m highly motivated to help other families because nobody should have to do this.”

If you need help

National Suicide and Crisis Lifeline: If you or someone you know needs support now, call or text 988 or chat at 988lifeline.org.

NH Rapid Response Access Point: If you or someone you know is experiencing a mental health and/or substance use crisis, call/text 1-833-710-6477 to speak to trained clinical staff.